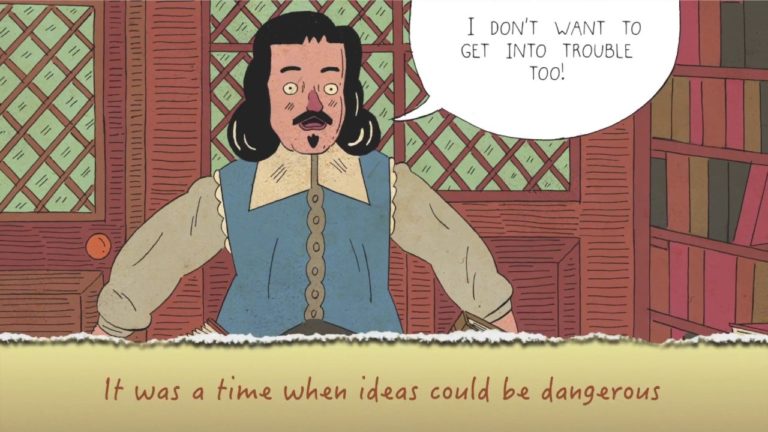

Picture the scene. It is almost 2am and you’ve been out for the evening with friends, and now you’re walking home. You are on a quiet street, next to the fencing surrounding a building site. There’s an access road that runs through the plot of land, and you know that if you slip inside, it’ll knock some time off your walk home in the cold early hours of the day. So, you do exactly that and then suddenly, before you know it, you’re a ghost.

That’s what happened to one unsuspecting woman on the 18th of August in the centre of Birmingham. Don’t worry, she didn’t die – but she did get captured on CCTV as she strolled through a building site. The camera in question belongs to Limitless Security and at 1:53am the Managing Director, Adam Lees, received an alert to tell him that something had been captured moving on one of their cameras. The news broke the next day on the BirminghamLive website where Lees is quoted:

“[i]n the early hours of Tuesday we had an alert to say a motion-sensor camera had picked up movement on the site… I checked and saw that picture. I notified security on site straightaway who did a patrol but found nothing. It’s incredibly strange. I have no idea what it could have been, but I didn’t sleep the rest of the night.”

You might ask what could be spooky about a woman cutting through a building site. Although she was wearing a red dress, the CCTV camera was using a night-vision mode and as movement was detected, a motion-sensor light was triggered alongside the camera. The woman in a red, floor-length dress suddenly became a luminous white figure wearing a long, flowing white dress and floating past the camera.

Soon, people were sending the photo to me because they wanted to know what it could be. On the first day the photo made the press, I gave it a quick glance and decided that it was either a person or someone messing around. However, my job was demanding my time and I thought nothing more of it. Only, this was a ghost that wasn’t going away, and the image began to spring up all over the internet, so I decided to try and find out what was going on. Was this a simple misidentification, or was it a deliberate hoax? I don’t like to think ill of others without just cause and I couldn’t see a motive to hoax a ghost photo like this. After all, Limitless Security were approached by the press and hadn’t approached journalists themselves. Lees’ daughter tweeted the image to her followers because they were baffled by what had been caught on camera and it got picked up from there.

There’s nothing to indicate forgery so there had been a person in front of the camera which meant that either someone had been mistaken for a ghost, or the photo had been staged… or it was actually a ghost. I decided it was best to speak directly with those involved and contacted Adam Lees, and although I was expecting no response at all (as is often the case) I was pleasantly surprised when Lees responded that not only would he answer my questions, but he wanted me to know that ‘there’s nothing paranormal about [the photo].’ Lees explained that ‘the image is 100% genuine but it is of a lady walking through the site. It had us all baffled at first but a few days later we discovered a separate CCTV camera had picked her up’.

The separate camera belonged to Stewart Chapman, an electrician working on the Sherborne Street site. A screengrab of Chapman’s footage was floating around social media and shows that the ghost in a flowing white dress is actually a woman in a red dress. I asked Chapman what had happened, and he told me:

“We have all of our CCTV active as we are about to hand over the first three blocks of apartments. Where Limitless Security have their camera, I have a CCTV camera positioned directly above it, but nobody knew that it was active. When we received the email from Limitless Security saying there was a ghost on site, we all thought it was fantastic until I noticed where it was and thought “I have a camera above there!” So, I went through the footage and found the two ladies wandering onto the access road.”

I shared the screenshot from Chapman’s footage on my blog and considered this a shut case. However, a few days later I received an email from a marketing agency acting on behalf of 300- Security Services. They’re the company who had patrolled the site on instruction from Adam Lees. A woman named Sarah told me that she was working ‘on behalf of the security company that visited the scene of the Birmingham ghost.’ She offered to send me the press release and (perhaps naively) I thought that it would be about the folly of security staff getting spooked before discovering that the ghost was a living woman. However, what arrived was a release under the title ‘Time to be alarmed? Security firm on hand as Birmingham’s answer to the ‘Ghostbusters’.

The release reads:

‘From mysterious movements at night to unexplained disturbances in the day, there aren’t many callouts that shock the team at 3000 Security. But a recent disturbance on a building site in Birmingham was enough to make the team’s hair stand on end. Arriving on-site minutes later to undergo a full patrol of the area and scouring the security footage led to more unanswered questions. The image clearly showed an eerie-looking figure dressed in white, in front of the site’s security fencing.

Darrell Coghlan, Managing Director at 3000 Security said: “We’re used to calls about

unexplained disturbances at night – but never have we seen proof like this. Although the site was confirmed as having the ‘all clear’, this has to be one of the spookiest calls we’ve ever been asked to assist with.”

The press release ends with: ‘whether you’re a believer or not, this mystery still stays unsolved.’

I emailed back to ask if Coghlan and 3000 Security Services knew that the mystery had been solved and why they were still promoting it in this manner. Their response? “No comment.” Sometimes when you say nothing it speakers louder than words and that is certainly true in this case.

Although it’s clear that the photo wasn’t staged, it has certainly been milked for all it’s worth by those involved which leads me to conclude that if there’s something strange in your building site, who you gonna call? Probably not security…