Summer 1945, the end of the Second World War. Europe lies in ruins, tens of millions are dead. The Axis powers are no more, with Nazi leader Adolph Hitler dead in a ditch, his body covered in petrol and set on fire, while Italian dictator Benito Mussolini hangs upside down from a lamp post. In the east, Joseph Stalin has the Soviet Union in his vice-like grip. In the words of Winston Churchill, an iron curtain is descending over Europe. Already, western leaders are discussing how to defend themselves should another world war break out.

Following a series of meetings in the late 1940s, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, or NATO, was born. The initial premise was simple: should one member of the alliance be attacked, the other members would come to their aid, as set out in Article 5. Although not set in stone, the de facto power NATO counteracted was the Soviet Union. They reacted in 1951 with the Warsaw Pact, a treaty that saw the Soviet Union formally ally with several Eastern Bloc countries, including the former East Germany.

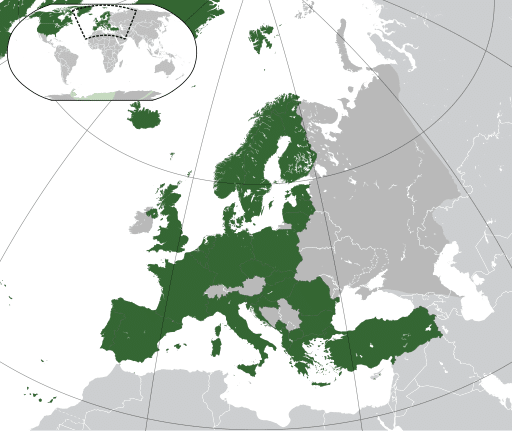

The Cold War between the east and west lasted until 1991, when the Soviet Union, under the ailing presidency of Mikhail Gorbachev, collapsed. From it emerged 15 new countries, with Russia being the largest and most powerful. Rather than disbanding, NATO engaged with the former Eastern Bloc countries. The NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council was set up in 1998, while NATO expanded in 1999, welcoming Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic. The expansion continued throughout the noughties with a raft of countries joining in 2004, including the Baltic states (Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia). This, combined with their membership of the EU, marked a remarkable transformation for the Baltics after they spent 50 years forcibly incorporated into the USSR.

But, has NATO been a force for good or, as its critics would claim, an instigator of war? After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, starting a war that is still grinding on over three years later, a new slogan emerged from the Stop The War Coalition, backed by prominent politicians such as the former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn: “No to war, no to NATO expansion”.

The narrative here is that NATO is somehow responsible for Russia invading Ukraine. To unpick this, we need to first examine how NATO works. Unlike the former Soviet Union, NATO does not expand by conquest. Members have to apply. If they meet the application criteria and their membership is ratified by all existing members, they are allowed to join. As Russia is not a NATO member, it does not get a say in which countries can and can’t join. So, the membership of countries such as the Baltic states cannot be seen as provocational. The Baltic States wanted to join, as is their right as independent nations. They applied and were accepted, they were not coerced or conquered.

Russia may complain about “encroachment”, but the truth is it has shared borders with NATO countries for over 20 years. In fact, the Baltic exclave of Kaliningrad, the westernmost part of Russia, is surrounded by the Baltic sea to the north, Lithuania to the west and Poland to the south. The entirety of its land borders are with NATO countries. If NATO wanted to annex it, they would have done so a long time ago. NATO has never invaded Russian territory, and has no plans to do so. If Russia believes NATO is a military threat to it, the threat is 100% perceived and not at all real.

A supposed reason for Russia invading Ukraine back in 2022 was to prevent Ukraine joining NATO. Although this was given post hoc, with the actual reasons given by Russia at the time being “denazification” of a country with a Jewish president and stopping a non-existent genocide in the Donbas, it was far from valid. Ukraine is its own country with its own agency, and whether it wants to join NATO or not is not Russia’s business. Russia does not get to dictate which international organisations its neighbours can or can’t join, even if they share a border.

A claim often repeated by Russian president Vladamir Putin is that Mikhael Gorbachev was promised that NATO would not “expand one inch eastwards” by US Secretary of State James Baker. This notion comes from the tumultuous days around 1989, when the world order was in a state of flux. For decades, the USSR adopted the Brezhnev Doctrine, a foreign policy whereby any country within the Soviet sphere of influence that appeared to abandon socialism could be invaded and subjugated. This happened to East Germany in 1953 and Hungary in 1956. The Czech Republic’s Prague Spring was crushed in 1963. With the rise to power of Gorbachev in 1985, the Brezhnev Doctrine was abandoned. One by one, the Eastern Bloc countries overthrew communist regimes in the revolutions of 1989, culminating with the execution of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu on 25 December 1989.

East Germany’s socialist government collapsed and the Berlin Wall fell, ending 40 years of the German Democratic Republic. Discussions began in earnest as to how to resolve the German question. Although a unified Germany may seem obvious now, back then the idea was met with opposition, including from British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who genuinely feared that a unified Germany could once again start a world war. On 9 February 1990, James Baker met with Gorbachev in Moscow. The topic of NATO expansion came up, and Baker uttered his famous words. Nothing formal came from this promise, and no treaty establishing it was ever signed. In addition, Gorbachev was President of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union no longer exists. In fact, after it dissolved on 25 December 1991, Gorbachev was left out in the cold with no political power whatsoever. Any verbal promises made to him back in the early 90s have no meaning today.

Another criticism levelled at NATO is that it is a dinosaur of the Cold War, it has gone way past its sell-by date. However, although the Soviet Union was seen as “the enemy” back in those days, no specific nation or power is referenced in the articles of NATO. The world is an uncertain place, and no one can say where the next threat will come from. Following the Cold War, NATO represented over 40 years of international military cooperation, there was no rush to disband it. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, NATO has been involved in several military operations that have gone beyond simply defending the alliance. These include maintaining a no-fly zone over Bosnia, blockading the former Yugoslavia, and patrolling the skies over Libya during the final days of the Gaddafi regime. All of these actions were part of complex geopolitical situations, nearly always involving a United Nations mandate.

Today, NATO is very much active. After Russia illegally annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea in 2014, it was clear that a country that bordered NATO states was prepared to invade its neighbours. Following a summit in Warsaw in 2016, the Enhanced Forward Presence, or EFP, was created. This operation has seen thousands of troops deployed throughout NATO’s eastern flank, in an effort to deter any aggression.

To this day, no NATO member has ever faced direct military action from a third party state. Article 5, which states that an attack on one is an attack on all, was only ever invoked once, and that was by the USA following the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001.

The knowledge that powerful allies will come to your aid if you are attacked is highly appealing today. After Russia invaded Ukraine, Finland and Sweden abandoned decades of neutrality and decided that NATO membership was right for them. After objections from Turkey were overcome, the two Scandinavian nations were admitted, increasing the length of NATO and Russia’s border by over 800 miles. Once again, NATO expanded through mutual agreement and not through conquest.

NATO’s primary function remains: it is first and foremost a defensive alliance. The main reason for joining is very simple. If you’re in NATO, you don’t get invaded. If you live in a Baltic state that shares a border with a country that subjugated you in the days of the Soviet Union, not getting invaded is very, very appealing indeed.