This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 3, Issue 5, from 1989.

In January 1988, reports of UFO sightings over Australia’s Nullarbor region were widely reported in the Australian media. The editor of the Star ‘newspaper’ judged the story to be of sufficient interest to merit front page treatment in its January 22 edition. On the request of Popular Astronomy editor Ian Ridpath, retired meteorologist A.T. Brunt conducted an investigation into the sightings. This is his report.

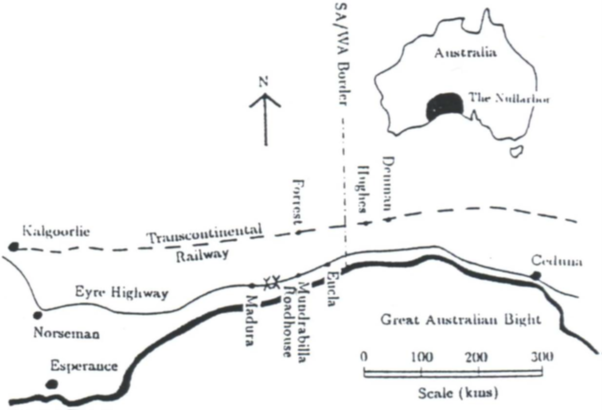

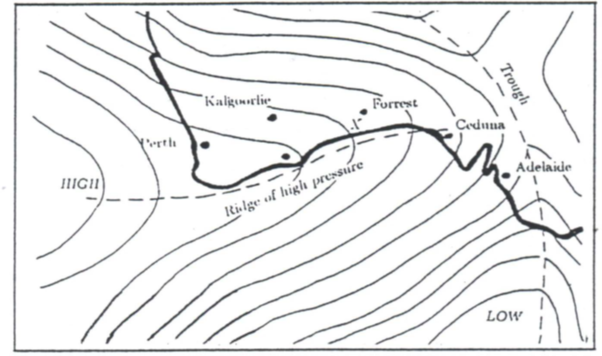

Quite a few unusual lights have been sighted over Australia’s Nullarbor Region, but none have received the notoriety of the two 1988 incidents. There are no towns of any size between Ceduna and Norseman or Kalgoorlie (Figure 1); most are railway sidings or road settlements of just a few people. Although the Eyre Highway runs closer to the coast than the Nullarbor Plain itself, the whole area has become known as the ‘Nullarbor’. Between Madura and Eucla, an area known locally as ‘The Basin’, there is a line of 100m hills to the north, but east of Eucla the highway is located on higher ground.

It really is a perfect area for ‘UFO’ spotting. The dry, desert conditions give rise to decreased cloudiness, there are no city lights to distract the spotter, road and rail traffic is fairly sparse and the horizons are so flat and wide. There is an awesome splendour about the night skies there that has to be seen to be appreciated.

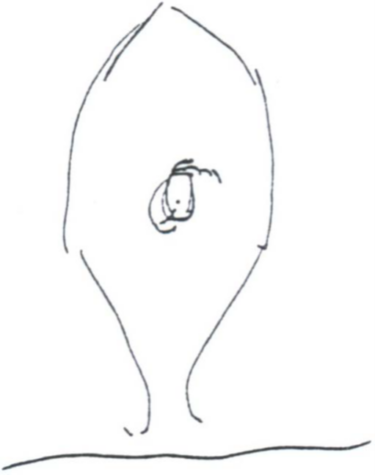

The first of the 1988 incidents occurred about 4:20 am Central Daylight Saving Time (CDST) on 20 January, when the Knowles family was travelling eastwards on the Eyre Highway. About 40km west of the Mundrabilla Roadhouse, they saw a light over the road ahead of them. At first they thought it was the light from a truck approaching them from the east, but the light became brighter and bigger, frightening them into taking evasive action. The driver of the car said that the light appeared and disappeared ‘after jumping about a bit.’ He described its shape ‘like an egg in an eggcup and about 1 metre wide’ and its colour as ‘bright and white with a yellow centre.’ His sketch of its shape was included in newspaper articles (figure 2).

There were other vehicles within 30 or 40km but the occupant of only one, a truck driven by Graham Henley, reported seeing any unusual light. He was driving east some distance ahead of the Knowles’ vehicle and said he saw a light that was ‘too high up to be another truck or vehicle’, it was ‘white and yellow in colour’ and it ‘disappeared and reappeared’. The crew of a tuna boat fishing in Bight waters ‘hundreds of kilometres away’ also saw a strange light on the same night and it was elongated in the vertical, but no direction or elevation of this light was reported.

The Knowles family claimed that their car was picked up by the ‘UFO’ and as it was dumped, a tyre burst. They also claimed that a black ash covered the car and that there were indentations on the car’s roof. They drove off at high speed and were obviously very distressed and somewhat hysterical when first interviewed.

Their vehicle was subjected to thorough inspections on several occasions by the Police and various UFO research groups in Australia, but none of these inspections showed anything unusual about the car. There was no black ash inside or outside the car; the only addition was a black deposit on the metal rims of the two front tyres, which was consistent with material from the brake linings. The rear right-hand tyre had burst in a normal manner, such as one would expect from a vehicle driven at high speed, leaving some rubber marks on the wheel arch. The dents on the roof were insignificant, and there was no proof that they were not there before the event. So there was nothing mysterious, only the unusual, egg-shaped white and yellow light they saw. The second incident occurred about 1 a.m. Central Standard Time on 17 October 1988 in roughly the same area. There seems no doubt that the first incident helped to precipitate the second. A bus, driven by Mr Peter Chapman with 25 passengers on board, was travelling westward along the Eyre Highway about 20km west of the Mundrabilla Roadhouse. The driver saw a light on the righthand (northern) side of the bus and woke five of the passengers who also saw the light.

Newspaper reports said that the driver was ‘terrified’ but he evidently wasn’t sufficiently terrified to waken the other 20 passengers sleeping in the bus. He didn’t stop to observe the light, which he described as ‘a bright white light which appeared to be hovering about 20m above ground and giving the impression that the light was moving. ‘ He also said that ‘the bright light followed the bus for about 10 miles as they travelled at high speed to escape.

One passenger said she saw the light in the driver’s mirror; she thought ‘it was a reflection of the headlights of a transport behind the coach.’ The highway tends slightly south of due west in this sector and, with comments like ‘on the right-hand side’ and ‘in the rear-view mirror’, it does seem that the most likely direction of the light was from the north-east. No unusual effects on the bus and no unusual marks were reported. Also, there were no comments on the shape of the light which the driver said was ‘not bright enough to illuminate the bus or the surroundings’.

Investigation of the weather conditions prevailing at the time of these incidents showed that each was characterised by fairly cloudless and calm conditions, although such conditions resulted from differing meteorological situations. In order to find a factor which might be common to both incidents, their salient features have been extracted and listed in Table 1 for comparison purposes. Apart from the fact that they both occurred on the Eyre Highway west of the Mundrabilla Roadhouse, there seems to be nothing which one could say was definitely common to both incidents.

| Feature | 20 Jan 1988 sighting | 17 Oct 1988 sighting |

| Location | About 40km W of the Mundrabilla Roadhouse | About 20km W of the Mundrabilla Roadhouse |

| Time of year | Summer | Spring |

| Direction of travel of observers | East | West |

| Likely bearing of light | From east | From north west |

| Shape of light | Vertically elongated | Not specified |

| Claimed physical effects | Car lifted, black ash, etc | None |

| Prevailing weather conditions | Strong high pressure area W of Perth. Very pronounced ridge of high pressure along the whole southern coastline of W.A., extending as far east as Ceduna. 0-2 eighths low cloud, very light winds | High pressure area of the head of the Bight. Almost cloudless. 1-2 eighths high cloud. Very light winds, e.g., Forrest E 2 knots |

| Upper air temperature | Temperature inversion at For- rest 3800 to 5300 ft approx 5°. Greatest increase in temperature near the top of the inversion layer. Stronger inversion in the ridge of high pressure along the coast, e.g., Esperance 8°C | Marked temperature inversion. 1000-1400 ft, 8°C at Forrest. Greatest change of temperature near bottom of inversion layer |

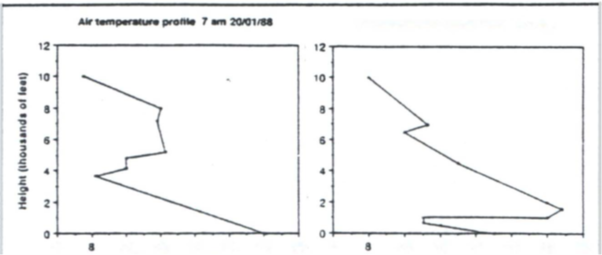

That is, until the upper air temperature profiles are examined. In each case, the nearest temperature sounding (Forrest, about 1 00km to the south) showed a marked temperature inversion – that is, warmer air overlying colder air. These soundings are shown in Figures 3(a) and 3(b). Again, one can pick out differences in the two profiles, but the fact remains that on both occasions there were marked departures from the usual temperature decrease with height.

The meteorological situations are interesting. The surface weather chart for 6 am CDST 20 January 1988 (Figure 4) shows a pronounced ridge of high pressure extending along the whole of the southern coastline of Western Australia from a High centred well west of Perth. This is quite unusual for a summer chart. The ridge was over 1000km in length and, as ridges associated with subsiding air and increased stability, it is understandable that the Forrest inversion was not an isolated one. In fact, inversions were evident over the whole 1000km (plus) length of the ridge from Ceduna to the SW corner of Western Australia, but they were much stronger along the coastline; for example, at Esperence the inversion was 8° C.

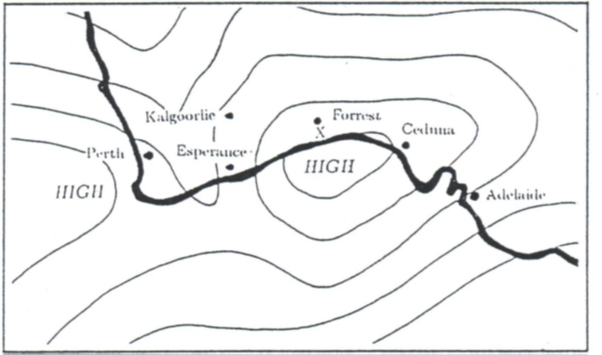

The surface chart for 3 am CST 17 October 1988 (Figure 5) is a little different. It shows a large high pressure area over the head of the Great Australian Bight, again with evidence for widespread inversions over the Bight area. All the evidence showed that the inversion at Forrest was representative of the area where the sighting took place.

The refractive properties of inversions have been described in many meteorological texts, but, in view of the general lack of knowledge about meteorological optics (even among scientists) it is appropriate to summarise what refraction does in the lower levels of the atmosphere.

We all know that light travels in straight lines provided the medium is homogeneous. For most of the time, the atmosphere acts as a homogeneous medium, but there are exceptions when sharp discontinuities in the vertical structure of the air cause aberrations in the straight line path. And one of the main discontinuities is a pronounced temperature inversion when there is a sharp density difference in the air above and below the inversion. This causes refraction and the path of light is bent downwards, giving the impression that the object is seen much higher than it really is.

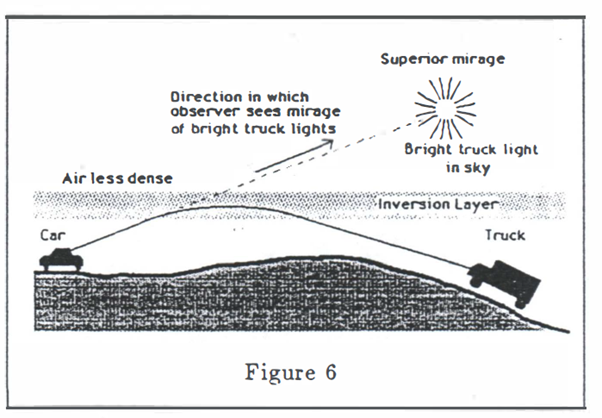

For example, the wave fronts from a distant light source on the Earth’s surface will be quite regular until the upper part of the wave front passes through the inversion. Here the temperature is higher, the speed of light is fractionally greater, and this part of the wave front is speeded up. Such a distorted wave front (upper part speeded up, lower part retarded) may reach an observer in a suitable position and his eyes see an image (normal to the wave front) in a position which is well above where the surface light source actually is. Such an image is known as a superior mirage (see Figure 6).

The Glossary of Meteorology defines a mirage as ‘a refraction phenomenon wherein an image of some object is made to appear displaced from its true position.’ The key word is ‘displaced’, but it is important to realise that distortions of shape, colour, size and intensity also occur. These distortions obviously make identification of the object more difficult.

Even under the most steady meteorological conditions with a simple temperature profile, when it is possible to see a good identifiable mirage for many minutes, it should be stressed that the air is moving and the path taken by the light reaching the observer’s eyes is subject to changing meteorological conditions. When the temperature profile is more complex, multiple images may appear, some in grossly distorted forms with unusual colouring. Some of the distorted forms can fool even those quite used to the characteristics of refracted images.

When either the observer or the object is in motion, the images can appear and disappear quite rapidly or they can seem to perform rapid gyrations creating the illusion of extraordinary spacecraft. In addition, interference between incident and refracted rays can produce complicated mirages whilst focussing of the rays can ‘cause bright and dazzling images which jump about or even disappear at the slightest movement.’

When an inversion is horizontally extensive, such as in a long ridge of high pressure, it is possible for light rays to be bent several times following the shape of the earth’s surface, in much the same way that radar ducting takes place. When there is a wide horizon and an extensive inversion, it is possible to see the mirage of a light which may be 100-150km away. The light is usually on the earth’s surface but the refracted image (often distorted) can appear as a light at low elevations in the sky.

It is important to remember that the atmosphere can act as a lens under refractive conditions and the size and intensity of images can be magnified many times. The magnification can be so great that large objects, like mountains or islands have be ‘seen’ at sea over verified distances of up to 1000km (The Marine Observer, 1981). Each instance of long-distance mirages is associated with a pronounced and widespread inversion, such as those found in long ridges of high pressure.

Some of the best examples of refracted lights in Australia would be the ‘Min-Min Lights’ of Queensland. Invariably, there is never a sound or any physical trace when these ghostly lights are seen bobbing up and down above the treetops. In each case, there is ample evidence for a marked inversion and the direction of the ghostly light fits in with the direction of a distant stretch of highway, sometimes 100-150km away. The brighter lights come from truck spotlights at high beam (used to avoid kangaroos and wandering stock), but Min-Min lights have been known to be caused by distant cars. These bizarre lights in the sky are never seen on windy nights, or cloudy nights, only on the occasions when it is fairly calm and clear, the atmosphere being stable enough for inversions to occur.

And the Nullarbor lights are the same. You will never see them on windy or cloudy nights. On clear, calm nights passengers waiting at sidings on the long, straight transcontinental railway line have reported seeing the light of an approaching train for at least an hour before it actually arrived. At the normal train speed of 110 km per hour, people must be able to see the headlight of a train which would be at least 110km away at the time. It first appears as a light in the sky and only in the last 10 to 15 minutes does it ‘come to earth’, as it were. Australian National Railways advise that, at high beam, these lights are of approximately 2000 candle power; no wonder their refracted lights can be seen at such great distances over the flat Nullarbor. The Brown Mountain UFOs (Klass 1974) are good examples of refracted lights from American trains, but in much more irregular country.

The very scattered road traffic over the Nullarbor must also generate mirage-like lights in the sky, particularly some of the interstate trucks which are specially equipped for night travel. Campers on the Nullarbor report strange lights at times, some of which could perhaps be attributed to activities at the Woomera rocket range. It is interesting that one of ·Australia’s best hoaxers, the Nullarbor Nymph (Geniece Brooker Scott) spent many nights posing as a wild girl living with kangaroos and confirmed that she has seen lights in the sky; she said ‘they could be meteorites or satellites-or something else!’

To return to the 1988 incidents. The unusual lights seen on both occasions were obviously refracted images of distant light sources, because both occasions were associated with pronounced temperature inversions. If additional confirmation is needed, the light seen on 20 January 1988 ‘jumped about a bit’ typical of refraction focussing and was elongated in the vertical, which fits the towering type of distortion one would expect from the inversion shape on that particular night. The inversion on 17 October 1988 should have given rise to a squat (horizontally elongated) image, but Mr Chapman did not specify its shape.

It is one thing to be confident about refraction causing an image in the sky, but quite another to find out what actually caused the light which was refracted. So much depends on the attitude of the light source and the height and strength of the inversion that it is difficult to specify what distance would result in the type of focussing necessary to produce a bright and dazzling image.

Let us consider the observed facts on both occasions. The Knowles family on 20 January saw the light to the east which they ‘first thought was a truck approaching from the east’. There were no bright astronomical bodies in that direction and the sun was 29° below the horizon; besides, its azimuth was 145°. There were, however, several vehicles, both eastbound and westbound on that section of the Eyre Highway at the time (Basterfield and Brooke, 1988). Although some of the other drivers reported no unusual lights, it should be remembered that this is typical of refracted lights.

It is difficult to determine which vehicle was in the correct position to permit focussing of the refracted light and cause a ‘bright and dazzling image’, but one cannot rule out a westbound vehicle descending into Eucla (100km to the east) because of its elevated position. A vehicle at that distance would not have been considered to be part of the incident.

This leads to the conclusion that the first impressions of the Knowles family were correct, ie, that it was indeed ‘a truck approaching from the east’. It was the distorted image of its headlights which was so frightening and bizarre. All the other things that happened to their vehicle were either of their own doing or their own imagination whilst in a state of fright, as none of their claims in this regard were substantiated by inspections of the vehicle.

The vertically elongated image observed by the crew of the tuna boat on the same night would obviously have been from a different light source. Nevertheless, the tuna boat was still near the ridge of high pressure and the same widespread inversion would have covered its position. So they too would have observed a refracted light in the sky but, without any direction indicators, it would be impossible to say what the light source was. The most obvious choice is another ship.

In the second incident, the light appeared to be ‘hovering about 20m above the ground’ and ‘on the right-hand side of the bus’, the most likely direction being from the north east. Basterfield (1988) identified the light source as being the planet Jupiter and indeed its position (azimuth 040°, elevation 26°) seems correct, especially as the observation was made over a line of low hills and the sky was almost cloudless. There is no doubt that refraction in the inversion layer would have changed this normally bright light into a distorted and enlarged image. In addition, it was recorded that the driver and passengers were aware that they were almost exactly in the area of the first incident nine months earlier and they certainly would have been looking for lights.

It is interesting that Australian National Railways advised that there was a westbound goods train between Denman and Hughes, approaching the WA/SA border at the precise time and date. The bearing of this light was 040° from the sighting position but the distance (170km) puts it slightly out or range, especially in view of the line of 100m hills between the headlight of the train and the observer. Nevertheless, mirages have been observed over that distance. In view of the fact that the bus driver and the passengers saw only one light, it must have been the planet Jupiter. They would not be the first to call planets ‘UFOs’; this is quite easily done when refraction distorts their normal shape and intensity.

So, if anyone is looking for UFOs (strange lights) they should certainly try the wide open spaces of the Nullarbor. But stay near the highway as this is the best producer of unusual lights. Never choose windy nights or cloudy nights; it is necessary to have the faintly calm, clear nights which are indicative of inversion conditions when refraction occurs. Best of all, choose a night when the high pressure centre is near you or a long ridge of high pressure extends over you. Even though there is a roadside sign near the WA/SA border warning travellers to beware of UFOs, it is hoped that you will be better informed. There are quite a few occasions each year when pronounced inversions cover the area, so be on the look-out for them. However, the type of refraction focussing such as the Knowles family experienced is much rarer; the light source has to be at the right focal length and the height and length of the inversion have to be just right for a large dazzling image to appear.

If you see a strange light, stop, note the time and take rough bearings of the direction and elevation whilst watching its movement, reporting this to the nearest police. There is no need to be alarmed or to panic like the Knowles family; no-one has ever been hurt by such lights. Rest assured, we are not being invaded by extra-terrestrial beings from wherever-the unusual lights are naturally occurring refraction phenomena. Many of the ‘UFO’ interpretations seem to come from people who ignore the known wonders of our atmosphere; they seem to be unaware that science fact is much more wonderful than ‘UFO’ fiction.

References

- Basterfield, K. & Brooke, R., The Mundrabilla Incident – January 20th 1988, UFO Research Aust. Newsletter, April 1 988.

- Basterfield, K., The Mundrabilla. ‘UFO’ of October 17th 1988, UFO Research Australia., 1988.

- Corliss, W. R., Handbook of unusual natural phenomena, Sourcebook Project, USA, 1 977.

- Humphries, W.T., Physics of the Air, McGraw-Hill Book Co., London, 1929.

- Klass, P. J., UFOs Explained, Random House, New York, 1976.

- Sheaffer, R.S., The UFO verdict, Prometheus Books, Buffalo, 1981.

- The Marine Observer, Vol. 61, No. 1 ,232, April 1971.

- Viezee, W., ‘Optical Mirage’, extract from Scientific study of UFOs, Condon, E., Bantam Books, 1969.