This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 4, Issue 5, from 1990.

For anyone possessing a television, a radio or, for that matter, the Friday edition of the Daily Telegraph it is difficult to avoid Stephen Fry’s pugilist’s nose, mellifluous tones and dry wit. The actor’s art does not give much scope for personal opinion but in his writings Fry’s irreverence for the irrational, his antipathy for the antiscientific and his intense disdain for daftness become apparent. In the Listener in December 1988, for instance he wrote ‘It’s extremely unlucky to be superstitious for the simple reason that it is always unlucky to be colossally stupid…’ It was in the context of this skepticism, unusual in actors who are generally regarded as a superstitious lot, that Stephen Fry agreed to be interviewed by the Skeptic.

It was perhaps appropriate on arriving at the Groucho Club for the interview that our conversation began with an unintentional spot of comedy. This resulted from the fact that I could not initially persuade the reels on my (borrowed) cassette recorder to turn round. The first recorded phrase of the interview was thus ‘…and you are an electrical engineer and you don’t quite know how to operate a cassette recorder…’.

But then (I suspect unusually for actors) Fry is quite at home with technology and is a keen user and programmer of Apple Macintosh computers. It would be tempting to think that this was perhaps natural for someone whose father is a physicist and a computer buff but, in fact, his father’s scientific, mathematical and musical abilities had the effect of initially pushing Fry away from these areas: ‘From an early age-and without wanting to be too psychoanalytic about myself – I think I probably gave up on things that I thought I could never compete with my father on. So I became far more interested in the arts and gave up piano lessons as soon as I possibly could-at the age of about eight-and went round claiming I had a maths block. But after I’d left Cambridge when I was a bit more grown up I became very interested in computers – I got an early BBC micro and then bought a Macintosh the year they came out and began programming and discovered I didn’t have a maths block at all.’

Although he was a student at Cambridge at the end of the seventies (1978-1981) this was a few years after the infatuation of the student community with Eastern religions. And although his mother’s family was religiously Jewish and his father’s family Quaker, western religion did not feature greatly in his upbringing either:

‘I had a sort of vague yen to go into the church when I was about 15 or 16 – I rather fancied myself in a cassock – but I think, generally speaking, I have always inclined towards what is loosely called liberal humanism. I’ve never really been strongly drawn to anything religious. This is not to say that I can’t be drawn towards anything spiritual which is not the same thing at all. But I’ve always, for as long as I can remember, had an irritation with things superstitious. I have a great belief in reason – the world is so remarkable and extraordinary anyway that to try and find things that are subject to no testing, no logic and no reason is ugly. The world is far too mysterious a place in its own right to try to add mysteries.’

Although he read English at Cambridge and took no science courses Fry nonetheless has a sympathy for science which is unusual in arts graduates, and does not feel that a scientific understanding of the world reduces our appreciation of it:

‘Just as there is nothing intrinsically dry and unspiritual about science, similarly there is nothing intrinsically mystical and irrational about the study of literature. Indeed, when I was at Cambridge we were going through the great structuralist debate and a lot of people were saying that the trouble with structuralism is that it is a rather scientific method, so that at linguistic levels you actually have complex formulas for the description of phonemes and so on. They felt that English should be about your response to a text, and there is of course room for that, but my view has always been that you don’t find the Lake District less beautiful just because you happen to know about the rock structure underneath it. If anything, geologists may even find it more beautiful because they see what Eliot might call the skull beneath the skin, which gives them a greater sense of the beauty of it. Similarly I have no patience for people who say that Shakespeare was ruined for them by having to study it at school; a further understanding of something never ruins its beauty.’

At this point Stephen Fry paused to blow his nose and remarked on the fact that for many years he had felt that he was immune to colds as he never seemed to catch them. Unfortunately, a few days previously, the Cosmos had responded to this false confidence by giving him the grandaddy of all colds – and in the acting world having a cold brings its own problems:

‘I would say the worst thing about being in a play is the moment you get a sniffle like I’ve got now, and you’re in your dressing room, suddenly there is a knock on the door and you hear:

“Stephen, hello it’s Lucy here. I heard your cough and there’s a wonderful little man in Camden Passage who does Bach wild flower remedies. Here’s his card.”

“Yes thank you”

And then there’s another knock:

“Would you like to borrow my crystals?” somebody else says. And it continues:

“Knock, knock” – “I’ve got four piles of vitamins. Here’s a bottle of vitamin C there’s one of vitamin B, one of vitamin D and one of vitamin K, which not many people know about.”

“Get out!”, I cry. “I’ve got a cold, for God’s sake leave me alone, I don’ t want your crystals, I don’t want your homeopathy, I don’t want your little weird spongy trace element pills that melt on your tongue. I don’t want any of this drivel, I just want a handkerchief!”

But he does proffer an explanation for this type of almost superstitious belief in unproven, quack remedies or formulae for self-improvement that seem so popular amongst actors and perhaps more particularly amongst actresses:

‘One of the explanations is that actresses careers are very difficult. They have to rely so much on their personal appearance, on their health, and on their skin quality, that they’re desperate for anything that they think might even have a 0.01% chance of making them fitter, or look better or glossier.’

Fry, himself, however, did not avail himself of a unique opportunity for self-improvement which he had seen on a TV programme:

‘I was so staggered when I saw some television programme about an American who is genuinely producing jeans with crystals sewn into a special gusset because he believes the crotch is the centre of consciousness and that the crystals resonate with some cosmic frequency. He’s making a fortune out of people buying jeans with bits of mineral in them.’

As lone skeptic in the midst of a generally credulous community of actors and actresses, an easy course of action might be to keep one’s views on homeopathy, astrology and psychic powers to oneself. Stephen Fry, on the contrary, expresses his views and expresses them forcefully. Andrew Lloyd Webber has a long-weekend party at his house in Newbury every year and often organizes a debate in the evenings. One year Fry was asked to propose the motion ‘Sydmonton (the name of Lloyd Webber’s house) Believes that Astrology is Bumf’ and was seconded by John Selwyn Gummer (of mad cow disease fame). The motion was opposed by no less a personage than Russell Grant who was seconded by the woman who taught TV ‘s cuddliest astrologer his mystical arts. Fry began his speech in blunt terms: ‘I said that not only does Sydmonton believe that astrology is bumf, it believes that it is crap, it’s a crock of horseshit, that it’s bullshit.’ But this rhetoric was followed up with some good skeptical entertainment as Fry had asked his agent to obtain ‘serious’ astrological readings based on information given to a number of astrologers about him, Hitler and various other persons. He proceeded to amuse the gathering by reading these totally inaccurate personality profiles thereby somewhat weakening the opposition’s argument.

Astrology is clearly a subject about which Fry has strong feelings (to be expected in a Sagittarius): ‘The constellations are all based on the parallax from which we view them so that it is totally arbitrary when we say that a particular constellation looks like, say, a pair of scales. Then to say, given that from this particular point of view this particular constellation looks slightly like some scales, someone born under it therefore is balanced is just the most insane thing you’ve ever heard. Or to say that someone born under Gemini, the twins, displays some kind of split personality, it seems so clear that this is just nonsense. And then people say “It stands to reason you know…” . It stands to all kinds of things, but reason is certainly not one of them.’

He recently participated in television programme on Channel 4 called Star Test in which celebrities are interviewed by a computer. The interviewee is alone in a studio with the cameras operated remotely and is asked by an electronic voice to select a topic and then to select a number from 1 to 5. So far so good – but the next question asked of him was ‘what is your star sign? ‘ – not a good question to ask the man who once said, in an interview with the Independent, that the length of his penis was likely to reveal as much about his personality as his star sign (–and no Freudian will disagree with that!).

‘… And so I refused to say anything and just stood up – you’re supposed to sit down – with the cameras following me, and spoke angrily about astrology for about 2 minutes. I expect they ‘ll cut this bit because I went on and on and on and on…’

Fry, when confronted with the there-are-more-things-inheaven-than-are-dreamt-of-in-your-philosophy school of logic, stresses the word ‘dreamt’ and insists that he also dreams of heffalumps, unicorns and tolerable estate agents. However he does accept that it is possible for people to have a significantly greater sensitivity to certain stimuli than most of us and that this can lead to, for instance, an apparent ability to dowse for water:

‘I was in the South of France recently where a friend of mine who is a great skeptic, Douglas Adams (author of Hitch-hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy), has a house. Now, all of Provence is desperately short of water, it’s the worst crisis they have ever had. If you want water you have to ring up for the water lorry and pay a vast amount of money to have your tank filled. It really is very, very bad. And he was talking to a chap who looks after a lot of houses belonging to English people in that area who was saying “well you either pay for the lorry each time it comes or you can have someone to come and dowse”. And indeed there are dowsers in Provence who make a fat living out of finding water for people.

‘Now, goodness knows I certainly don’t believe that a mystic power comes out of the earth but I do believe in hyperaesthesia and I know of a great many people who are able to read signs in a semiotic way; who are able, for instance, to see someone talking and know that he is lying simply because they are so good at reading signs that most of us don’t notice. Similarly, someone who is experienced in the kinds of places where water is likely to be, may well see patterns in the plants or geology of the area that indicate the presence of water – perhaps at a subconscious level. But he may genuinely believe that the water is influencing his dowsing twig. So I won’t dismiss dowsing because, in my view, anybody who can make a decent living by dowsing, amongst people as naturally cynical as the French, in an area where water is so rare must have some talent for finding water. But I don’t for a moment believe that there is any outside agency which is making the twig move’.

Another esoteric art for which Fry has a certain respect but without believing that there are any mystical elements to it – is the use of randomness to help gain insights into oneself or into problems: ‘I think the use of the aleatory in life is rather good. The I Ching for instance – which I don’t actually think any Chinaman believes to be particularly mystic – is a rather useful way of confronting anything. But the thing that you must do is think of the question you want to ask, ultimately, yourself. In fact, you can use any random event. For instance, you may have an important decision to make and what you can do is concentrate on the first thing you see out of the window – which could be a sparrow. You look at this sparrow with the question in your mind and anything the sparrow now does – via the natural patterning and metaphorical symbolizing abilities of the mind – will help you to come to grips with the problem. Essentially, you have the answer yourself but you just want to be shown an authority for it. Everyone needs a sense of some authority behind what they’re doing it, no-one wants to think of himself as being entirely alone and self-determining. In reality, of course, the real authority comes from oneself but we search for something to sanction what we’ re doing and rather reasonable things like the I Ching, ultimately, turn the authority back to oneself by the way in which one is obliged to frame the question.’

Tolerant of oracles and dowsers, vociferous in his opposition to astrology and quackery – but what is Stephen Fry’s particular bete noire amongst the mindless, mystical menagerie?

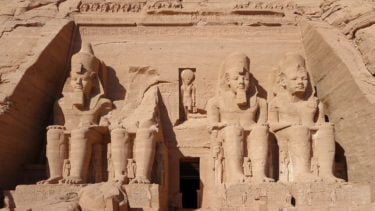

‘I suppose the one that really gets me going probably more than most is what the Greeks used to call metempsychosis – what we now call reincarnation. It doesn’t take much to realise that even at the rate at which we are increasing as a population, there are still many more dead people around than there are living ones. Therefore there is a surplus of dead people so that they can’t all be reincarnated – except as wasps perhaps, rather than WASPs. So I would love to hear one of these fatuous people who claim they’ve been around in previous lives just for once having lived in a period of time or as a person that wasn’t dramatically interesting. Why must they all have been a serving maid to Cleopatra or caught up in the persecution of the Jews in York or something that is so easily researchable, so pointlessly predictable?

And the other thing that really annoys me is the people who claim to have seen ghosts. They nearly always—because they think its going to impress you more – tell you about it in a rather matter-of-fact tone of voice. Whereas, if l was going to even vaguely begin to believe that someone had seen a ghost, I would expect them to be absolutely staggered because it turns upside-down one’s whole preconception about what the physical universe is.’ He leaned forward and gesticulated with his cup of cappuccino. ‘If I dropped this and it went upwards, I would be talking about it for the rest of my life. I wouldn’t just dismissively say “Yeah, it’s interesting – I let go of this cup and it fell upwards – would you like another cup of coffee?”. And similarly with ghosts. Seeing a ghost would overturn everything you understand about the universe around you. You would have to be excited about it. Yet the person who recounts his experience pretends he’s bored with it How can you take it seriously? The whole paranormal panoply gets me going. It’s all such ineffable piffle, isn’t it?’

I couldn’t have put it better myself.