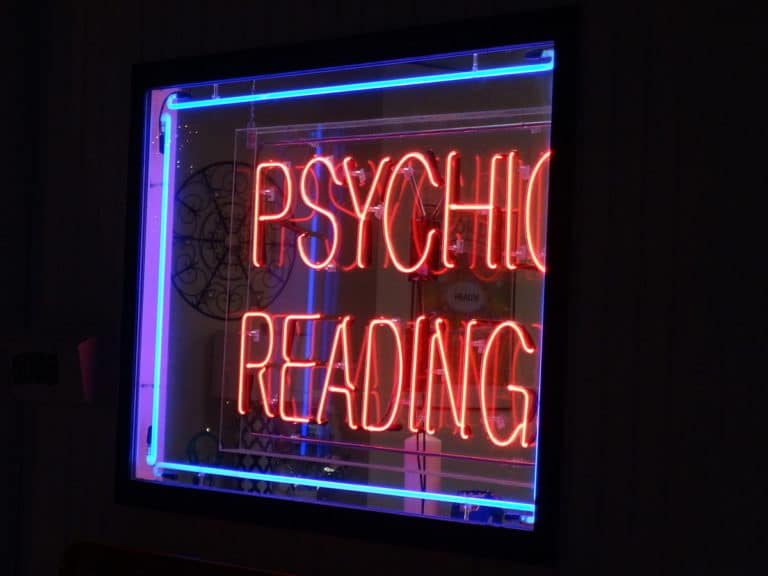

From time to time I get contacted by TV shows wanting a skeptic to spar against a psychic. This time a producer from Tiger Aspect wanted me for a show they were doing on psychics for BBC2. John Pocock, the producer went through all the questions that I’ve come to expect about the show – how to do testing, what they should look out for, ways to stop cheating and all that. He asked me if I wanted to appear on the show, and never one to say “no”, I agreed. John said that he would work on the concept over the weekend and send me details on Monday.

When John sent me the details, it looked like a reasonably sensible test. Here is the relevant portion of John’s email to me:

“Tomorrow, for our purposes we would like to start with an initial test that is quite straightforward, although this will lead to a more comprehensive one in the new year. The test involves you writing down 5 statements about yourself that are not on your website and that you have not mentioned to me, we will then place these in a sealed envelope which we will ask you to keep with at all times.

“The psychic claims he will be able to ‘read’ the exact information you have written down by his medium-ship and clairvoyance. We have made it clear that for his reading to be deemed successful he will have to get all 5 facts correct. We have tried to minimize the element of interpretation so the statements will only be seen by you and his answers must match your statements exactly. There will be time after the test for you to question him further if necessary.

“The psychic has not been told whom he is to be tested by and the production crew have not been told your name (it is only myself and the producer who are aware of your booking).”

I thought very carefully about this – I know it’s important not to choose obvious things, or things that are true about myself, but are also true for large numbers of other people, so I selected five things about myself, printed them, then sealed the paper, folded in half, inside an opaque bubble-wrap envelope. The bubble wrap inside made the light scatter, so when I held the envelope up to the light, I couldn’t even see the paper inside, let alone the writing. I was satisfied that my five facts were secure.

On the Tuesday, I went to the location they had selected – University College London, and things began as usual for TV. I waited. While I was being minded by a nice production assistant, another producer asked me to do a drawing for the reading. This made my internal Robbie the Robot worried: “Danger Will Robinson! Danger!” I know that there are lots of ways to discover the contents of a drawing – the most obvious is that when people are asked to make a drawing at short notice they tend to draw one of a limited range of ideas: a house, a boat, a smiley face or sun, a person or a flower. I therefore decided not to draw any of those. The production assistant was sitting there (although turned away) so I opened my newspaper and rested the bottom half on the table and used the top half to make a shield. This way they wouldn’t be able to get an imprint of what I was drawing on the table, nor could the assistant see me. I checked over my shoulder – I couldn’t see anyone there, or a camera, but I shielded the drawing with my body. After making my drawing, I drew a picture of a house on the newspaper, so that if they were watching my pen, they would see me draw a house. I folded the single piece of paper in half twice, and sealed it in their envelope. I kept both envelopes and the newspaper with me at all times, and no-one from the production team asked to touch them or look at them.

Soon after I had finished my drawing, it was time for my meeting with the psychic. I was taken one of the chemistry labs at UCL, where I waited some more with yet another producer. There was some more phaffing about (TV types love to do that!) and finally I was ushered into the presence of Shirley.

The lab was completely dark, except for a single fluorescent bulb bathing Shirley in a soft glow from the left-hand side of the table. Shirley was sitting at the end of a lab table turned lengthwise wearing a well-made three piece white linen suit with white coiffed hair, his hands crossed in front of him, and an imperious look on his face. I must say that my first impression was that he really looked the part!

I sat on a stool opposite Shirley and the director told me that Shirley and I were to have a discussion and then Shirley would tell me what I had written down and drawn.

The conversation began strangely and then continued in an even more bizarre way. I introduced myself to Shirley and we shook hands. I waited for Shirley to reciprocate, but this was clearly not on Shirley’s agenda. There was an awkward pause while nothing happened, and the director suggested that I tell Shirley why I was there, which I thought was odd because Shirley was supposed to be the psychic – and I thought it was obvious that I was there to participate in a “test” of his powers. Anyway, I began to explain that I ran a club called Skeptics in the Pub and Shirley interrupted with “septics in the pub?” It was at this point that I realised that Shirley was no ordinary psychic. Ordinary psychics are, in my experience, generally nice, pleasant people. They are friendly and polite. Shirley, on the other hand, was difficult, rude and aggressive. I said, “No, Skeptics” and continued with my explanation. Shirley then interrupted me and said that he would “prove the existence of the spirit world to me – either in this world, or the next.” Well, I thought, at least he doesn’t suffer from a lack of confidence. I asked Shirley if he knew about the spirit world, or just believed. Shirley said he knew and believed – because he could see spirits, but not just ordinary spirits mark you, famous ones. Apparently William Shakespeare had been in Shirley’s bedroom the previous night.

Now I was really intrigued – who were Shirley’s regular clients? What sort of person gives credibility to a psychic who claims to see William Shakespeare? This seemed to be stretching credibility, even for psychics! Where did the production company find Shirley? Didn’t they perform even the most basic tests on him themselves to establish his credibility? Nonetheless, Shirley had made a claim, so I felt it was my duty to examine it in the best way I could. “How did you know it was Shakespeare?” I asked. His answer dripped derision – “He told me!” he answered, as if this was the most obvious thing in the world. I endeavoured to point out that Shirley had not ever met Shakespeare, so how did he know that this spirit really was Shakespeare, or another spirit just claiming to be Shakespeare. Alas, I didn’t get far in this line of reasoning as I was interrupted by Shirley (this was to become almost the defining feature of the encounter). Shirley interrupted me by asking why I was trying to “undermine” him! Well, I thought, that’s the point of a skeptic on a TV encounter with a psychic!

Shirley looked down his nose at me, and said in a deep and what I took to be mysterious voice, “I know things about you”. I asked what he knew, and Shirley told me about my “shame and fear inside”. I wasn’t feeling shame or fear inside, so I wanted to know why Shirley thought I was. Shirley however had different plans – he wouldn’t talk about it “because of the cameras”; he wanted to protect my dignity from undue exposure on the tele. How thoughtful! This made me think more about the question of who Shirley’s real clients were – was his client list stacked with people who did have deep, dark secrets, so this rather unsubtle cold reading hook would find some purchase? I was in a different position however: I was there to test Shirley, and I knew that I didn’t have a hidden life that warranted “fear and shame”, and since I believed that that Shirley had special insight into me as much as I believed that the Moon is a giant marshmallow, I had no problems asking him for further “insights”.

I pressed Shirley, and despite his great protestations, I managed to get the following story: Apparently, in October I had been to a party, actually Sammy’s christening, where I got drunk and tore a woman’s dress, scratching her with my wedding ring in the process. This story was torn at my great insistence from Shirley “fact” by painful “fact”; at each new revelation Shirley at first coyly refusing to divulge the titbit (in order to spare my blushes) until finally he revealed the item at question. Shirley’s actions clearly demonstrated that he believed my personal shame was being exposed to a national TV audience, with him doing his best to protect me, while I recklessly insisted on the revelation of my own humiliation by the most gifted psychic of the age!

There was just one small problem with the story Shirley revealed: It was false in every detail! And not just a bit wrong, either! Totally wrong. I’ve never been to the christening of a child called “Sammy”, indeed I know of no-one by that name. Furthermore, I didn’t attend any christenings in October. I’ve never ripped a woman’s dress – at a party, christening or elsewhere; and, most tellingly of all, as the attendees of Skeptics in the Pub will attest, I do not drink – my drunkenness thereby being impossible. Shirley refused to accept my denials and greeted my teetotalism claim with a scepticism that would do Martin Gardiner proud – “You would say that, wouldn’t you?” intimating that I had a drinking problem! I suggested that I swear an affidavit to verify my claim, which was greeted with exclamations of “You want to swear on who?”, “Is David your child?” and “Why do you want to swear on a child’s life?” The interview was getting more peculiar by the moment!

But the whole “shame” thing was not as weird as the hypnotism stunt. At three junctures where Shirley and I had our greatest moments of disagreement, Shirley would snap his fingers and command, “Sleep!” and give me an instruction. This first was after I denied belief in the spirit world, Shirley “hypnotised” me such that when I “awoke” I would “see things as they really were”! Needless to say, his attempt at this was as successful as his attempt at divining my inner life, although after one of these episodes I expressed my belief that I thought Shirley would be good in stand-up!

My gentle reader will remember that the Assistant Producer had asked me to produce five facts about myself. They were, with numbers:

1. My first school was Hillsborough Primary School.

2. I buried Sweep the cat in the garden.

3. I am wearing green underpants today.

4. My favourite thing in Debrecen is the big yellow church.

5. My wife and I saw dolphins on our honeymoon.

It will not surprise my reader to learn that Shirley got exactly zero correct – however, you would be wrong! Amazingly, Shirley claimed he had managed to guess four out of the five statements! An impressive result, you’ll agree. Here are Shirley’s six responses:

1. Wine gums

2. Richard

3. Burger

4. Butt plug/anal plug

5. Peyton Park – alas, I can’t remember that this was exactly. It was a place I have never heard of.

6. Condom

In case you can’t work it out for yourself, the one Shirley agreed he didn’t get was number 3 – green underpants/burger. The reason he didn’t get that one was that he confused the lettuce on the burger and green of the underpants, and he was hungry. Shirley was adamant however, despite the producer’s earlier assurance that “his answers must match your statements exactly”, that the other four were direct hits! His explanation of this belief was thus:

1. I liked wine gums when I was at school (he later expanded on this with the suggestion that I was a very fat child at school and was taunted by my school-mates with taunts of “Porky Pig”).

2. Richard is the person who dug Sweep up.

4. (I cannot remember the connection between the big yellow church in Debrecen and a butt plug – I fear it was too horrible to be committed to memory!)

5. I would secretly rather have gone to the place mentioned by Shirley, than seeing dolphins on our honeymoon.

6. My wife and I are planning to have children.

I will leave it to the reader’s own abilities to work out the cogency of Shirley’s reasoning.

Next, we moved onto the drawing. I drew the symbol for pi: “π” with “3.14…” underneath. Shirley assured me that his drawing had been completed the previous night, and if it had been a picture of “π” with “3.14…” underneath then it would have been devastating for my case. But before we could get to the unveiling of the drawings, Shirley and I had a little set-to. Shirley insisted that I show my drawing first. I was equally resolute that Shirley, being the subject of the test, should reveal his effort first. Shirley attempted to resolve the dispute by use of his hypnotism routine. While the envelope was safely under my elbow on the table, Shirley snapped his fingers, and commanded, “Sleep! You will show me your picture when you wake!” Another snap of the fingers, “Wake!” I shook my head slightly, and looked at the envelope, which I picked up, and offered to Shirley, all with a slightly confused look on my face. Shirley had a perplexed expression as he reached out to take the envelope from me, at which point, I flicked the envelope away from Shirley’s outstretched hand, and said “Well that didn’t work, did it?” Eventually we agreed to open our drawings simultaneously.

Shirley’s “drawing” was actually dozens of drawings covering all the most commonly drawn objects – I saw a spade, a heart, a house, “e=mc2” and lots of other items. Alas, pi was absent. After a through search of the page, the best Shirley could come up with was an equation, which contained the square root of “n” as a component. Shirley triumphantly announced that this equation was equal to the value pi! I demurred from the conclusion that Shirley had scored a hit, but Shirley, with increasing vigour and rising anger, amid much table-slapping that he was right and I was wrong, demanded for the director a caption which would show that the equation was equal to pi! I did agree that for one value of “n”, Shirley’s equation was equal to pi, but then for different values of “n” it could be made equal to an infinite number of other numbers!

Our conversation was drawing to a close. In what I can only describe as a misguided attempt to… what? Impress me? Shirley said that Einstein was in the room with us. Shirley said he was attracted by the Bunsen burners. Apparently Einstein had neglected to mention to Shirley that while he was a scientist, he was a theoretical physicist who didn’t use Bunsen burners in his work. This observation appeared to enrage the already emotional and volatile man. Shirley screamed at me this was typical of my pedantic behaviour. Oh well, I suppose that asking for accuracy from a psychic could be described as pedantry!

After Shirley had calmed down somewhat, my parting shot to Shirley was very simple: “You are a terrible psychic”. He did not like that at all. We had a little shouting match when, for the first time (and to my great surprise) Shirley shut up and let me speak uninterrupted. I methodically went through every claim that Shirley had made and explained that all of them were false. Every single one. For someone whose confidence was so high at the beginning that he was going to prove the reality of the spirit world, it was quite a litany. As he looked at me in silence, I saw tears well up in Shirley’s eyes, and his lip start to tremble – I had made Shirley cry. His response was meek, “You like to destroy things, to grind them into dust.” “Of course I don’t,” I said, “but as a skeptic, I must go where the evidence leads me – you are a terrible psychic”.

The denouement was at hand, and it was quite a contrast to what had happened a scant few moments before. It became obvious that Shirley wanted to finish by saying directly to camera, “Yet another skeptic brought to his knees by Shirley Ghostman”. However this was such a blatantly absurd claim, that I turned to my camera and said “No he didn’t!” Shirley wanted, even needed the last word. Again and again he would say his concluding line and every time he did, I reiterated my denial. Shirley appealed to the director, but I simply said that they could do what they liked, but, while I was there, I would continue to express my disagreement. Shirley banged his hand on the table and threatened me, “I’m nearly loosing it!” Alas, it was too late for Shirley to have this insight – he had lost it some time before. Eventually, it became too much for Shirley. I wouldn’t let him have the last word he wanted, and he stormed out like a petulant child. I thought it was a fitting end to our dialogue.

After Shirley had made his dramatic exit, stage right, I turned to the director and said, “Sorry if I ruined you show.” He looked back and said, “Well, you did very well from your point of view.”

At the time, I could not fathom what the intentions of the programme makers were after. Shirley was such an unbelievably bad psychic – and histrionic, a Prima Donna, and an angry and aggressive person that unless their intention was to humiliate Shirley, I couldn’t see that there was any way this exchange would further knowledge into the testing of psychics.

The experience described in this essay represents the most bizarre and surreal experience I have ever had as a skeptic. Thanks, at least for that, Shirley.

Note

I did not take notes during the filming, which occurred on Tuesday 14 December 2004. However, I did make notes of the event that evening, and wrote this essay finishing on Sunday 19 December 2004. The items in quotes are therefore not direct quotes (with the exception of the John Pocock email) and I’m not 100% sure about the sequence of events but this is my best recollection of what happened. I have made every effort to be fair and truthful in this account,

The truth

We now know that Shirley Ghostman is a TV character, played by Marc Wooton. He is the star of “High Spirits with Shirley Ghostman”.

There were five skeptics who were contacted to do the show, in all: Chris French, Wendy Grossman, Tony Youens, Paul Taylor and myself. I met Paul at the filming (he was next after me) but I didn’t find out about the others until the next day.

We were all perplexed about the experience we had been through, which were all very similar. I couldn’t work out what was going on, but Chris thought the whole thing was a spoof – the rest of us disagreed, because why would anyone spoof us – we are skeptics, with a small to nil media exposure.

It was Wendy who found out the truth. Shirley was in reality Marc Wooton, and the show was a spoof.

The thing that annoyed us most was that the production company, Tiger Aspect, didn’t tell us that we were taking part in a spoof show. Their explanation was that they wanted our genuine reactions to Shirley, and if we knew it was an act, then they wouldn’t have got those; which I think is fair enough, however, they didn’t tell us after, either! This made us very suspicious, especially when we learned that Wootan’s previous project was “My New Best Friend” – an exercise in humiliation comedy. We were (justifiably, I think) worried that “Shirley” was just doing a number on us. We had lots of phone calls and emails with the Associate Producer, during which he told us that we weren’t the subject of the show – our purpose was to send Shirley up, but we didn’t believe him!

Chris French’s segment went first, on the second show. He was very relaxed after seeing it, and it put all our minds at rest! Wendy was second, and I was the other skeptic used.

My contribution appeared on the final show, on 19 April 2005. Of course it was heavily edited and featured only my introduction to Shirley, with the William Shakespeare bit; the whole drawing sequence and my disagreement with Shirley that she “brought another skeptic to his feet(!)”.

I have only seen the first High Spirits, and I will present a review of the whole series when I finally see it.

You can read more about our experience at Tony Youens’ webpage and Wendy Grossman’s blog as well as an article she wrote. Shirley’s homepage is here, and his page on the comedy website at the Beeb is here. The TV Tome give an episode by episode description.