This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 18, Issue 4, from 2005.

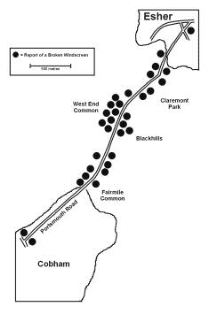

The last issue of The Skeptic outlined the panic and mayhem that ensued when the small English town of Esher apparently became the target of a mysterious sniper. The phantom gunman based himself on a four kilometre stretch of road between Esher and Cobham and, between December 1950 and December 1953, was alleged to have shot out the windscreens of at least 51 motor vehicles. A suspect was never even seen, let alone caught, and no bullets were ever recovered. As the number of incidents mounted so did the sense of hysteria in Esher, but who or what could be responsible?

What was happening on Hellfire Pass?

Trying to solve the mystery of the phantom sniper of Esher was no easy task. No firm solutions were offered at the time and no further work has been done in the fifty years since the trouble began. During this time much valuable evidence, in the form of local police records, has been destroyed. Nonetheless, the authors have the detailed records from the Esher News and Advertiser (ENA) and a few scraps of evidence from other sources (see The Skeptic, 18.3). From these we believe it is possible to test some of the possible solutions to the phantom sniper mystery and ultimately to offer our own opinion as to what exactly did occur on the Portsmouth Road during the early 1950s.

In this section we will test the four main theories put forward as the cause of the broken windows. More minor ideas, such as the ghostly highwayman and falling pinecones, are excluded because they are unworkable.

1. Supersonic booms

Early on, during the second wave of windscreen shattering, a national newspaper put forward the idea that sonic booms from low-flying military aircraft may have been responsible for shattering the windscreens on the Portsmouth Road. This idea was picked up by both the ENA and some of its readers.

The first acknowledged breaking of the sound barrier occurred in October 1947, only a few years before the Esher incidents. In the years following this achievement the term ‘supersonic’ entered popular culture as a euphemism for anything that was fantastic or great. There was, however, also concern over the effect of supersonic booms on local property, especially windows which could potentially shatter as a consequence. Although few, if any, people in Esher could ever have heard a supersonic boom at this time, there was already talk about the possibility of these noises being heard in the region, and the town itself is on the flight path from nearby Heathrow. It is probably for this reason that this theory gained local popularity. It is, however, a poor idea in practice.

The pattern of the windscreen shattering, as reported by the ENA and others, does not suggest a supersonic cause. Surely cars from a wider area would be affected as would the windows of houses, let alone the side windows of cars. It is also questionable as to how many supersonic aircraft there would have been operating in the area at that time. With the aid of hindsight we now also know that supersonic aircraft may well rattle a few windows, but they very rarely break them and then certainly not the toughened glass of car windscreens. Even the ENA rejects this idea itself.

2. Lone gunmen and naughty schoolboys

A chief reason for rejecting the supersonic boom theory is that in a large majority of cases motorists actually reported hearing an object strike their windscreen and in a number of cases there is clear evidence in the form of circular pock marks in the glass (e.g. Robert Bruce had a circular crack in his windscreen after driving along the Portsmouth Road on 4th June 1952). In the majority of cases it seems as though a missile of some kind is the most likely explanation. It is the origin of these missiles that forms the mystery.

Throughout its coverage of the windscreen incidents, the ENA favoured the idea of there being a genuine sniper hiding at the roadside and taking pot shots at passing cars. In favour of this idea are the tight distribution of incidents, most of which occur along the same short section of the Portsmouth Road, and the sound of a gun shot that accompanied many of the broken windscreens. With reports like that of Mr Tickner, who said he saw a flash and then heard an explosion just prior to his windscreen shattering, it is no wonder that a gunman was suspected. It is clear that at least some members of the local constabulary favoured this idea too, judging by their willingness to comb the surrounding countryside for evidence.

However, the one consistent problem with this theory has been the lack of a single bullet to be recovered from either inside the car or from the roadside. At other incidents where windows or cars have been shot at, the bullet is normally quite easy to find. The ENA and members of the local council overcame the problem of a lack of bullets by consistently advocating that an airgun must have been used.

An airgun is a light rifle which uses compressed air to fire light bullets, pellets or even stones over relatively short distances. They are low-powered and their ammunition fragile so whilst it might be possible for an airgun shot to break or damage a windscreen, the bullet itself would probably not survive the impact and certainly wouldn’t penetrate the glass to land inside the car. This would adequately explain the lack of a bullet at the scene of the crime. In addition, airguns are light, cheap and did not require the owner to a hold licence and so could easily have been operated by a local youth or other mischief-maker.

Although airguns vary in power and accuracy, it is reasonably certain that if fired from close range a pellet or rock from one could shatter a windscreen. Several experiments have been performed with airguns and windscreens, the results of which all show that airgun pellets can indeed shatter all types of windscreen glass.

Whilst it is certainly possible that there was indeed a sniper with an airgun hiding in the bushes surrounding the Portsmouth Road, there are a certain number of problems with this idea.

The first of these concerns the accuracy available from an airgun. Being low-powered, the effective range of most airguns is only a few hundred metres and, like all guns, their accuracy decreases with increasing distance from the target and with increased wind and rain. Despite all these factors the sniper seems to have been an uncannily good shot under all types of light and weather conditions. The sniper managed to shoot out the windscreens of dozens of cars accurately, without missing and hitting other parts of the car, most notably the bodywork and side windows.

On top of this the sniper was capable of doing it at night and in all weather conditions including on one occasion a snowstorm blizzard! To accomplish this, the sniper would have to be very close to the roadside indeed, and yet he or she was never once spotted by passing motorists, police patrols or people who have pulled over after having had their windscreens shattered. This seems very strange indeed.

The strongest piece of evidence in favour of a sniper is the case of Mr Frank Smith whose car was apparently hit on the driver’s door by a .317 bullet which left a sizeable hole (see The Skeptic, 18.3). All this would seem to point strongly in favour of Mr Smith having been shot at, but there are some strange inconsistencies noticeable in the reporting of this incident.

Firstly there is the calibre of the bullet which, at .317, is much larger and more powerful than the airgun pellets hitherto believed to be responsible for the other broken windscreens. Either the sniper had changed his means of operating or was using a different gun for this one occasion.

More puzzling though is the lack of any mention of a bullet being found embedded in the door even though, according to the ENA article, a ‘ballistic expert’ was involved in the case. However, the article never states that the ballistic expert actually examined the car, merely that he suggests that it could be a .317 bullet. Stranger still his assertion that the bullet could have “ricochetted [sic] off the road surface before hitting the panel”.

Does this imply that the angle of entry was such that the missile had to come from a downward direction, which would seem to be very odd indeed? We are not given enough information to decide, but this case has enough inconsistencies to suggest that either a bullet was not involved or that maybe this shooting is not related to the other windscreen incidents.

It is also interesting that despite this apparent prima facie case of a shooting along the Portsmouth Road, for several months afterward the police still maintained that there was no evidence of malicious damage to any of the cars involved in the sniper incidents.

A further suggestion made on a number of occasions was that schoolboys with catapults were responsible for the damage. A good catapult with a stone or steel ball-bearing could easily damage a car windscreen and could even be more powerful than some airguns. The suggestion that schoolboys could be involved came early on in the second wave of incidents, when a police sergeant told the ENA: “Perhaps it will stop when the children go back to school”.

However, the catapult theory, which was suggested on more than one occasion, has all the same problems of accuracy in adverse conditions as the airguns do. There is also the prolonged period of time over which the incidents occurred and the wide spread of incidents beyond the Portsmouth Road. All these work against the theory of non-mobile children with catapults. There is also only one windscreen broken at a time which suggests a remarkable patience for impudent children.

Interestingly, during some library research in Esher, one of the authors was approached by a local woman (to whom we shall afford anonymity) who said she was around the age of 12 when the sniper was in full swing. She claimed that many of the incidents were down to herself and her friends throwing tomatoes at passing cars, something that does not tie in with any of the ENA reports. She also mentioned that she knew of ‘older boys’ who were using airguns to take shots at car windscreens, but her stories sounded remarkably like those that are reflected in the ENA’s letter columns and may well have been based on local gossip at the time.

Although the sniper theory has some credibility to it, there are massive problems with the feasibility of carrying out this task with such accuracy over such a long period of time. It was a theory that was eventually dismissed by the police and is not favoured here either.

3. Inferior glass

The Automobile Association (AA) is quoted as saying that the damage was most likely to be due to inferior glass. The AA was consulted over this but could provide no further help, being unable to find any reference to the Esher incidents in their newsletters or press releases of the time.

It is unknown how inferior glass could be responsible for the Esher incidents except possibly being in conjunction with movements in the frame of the vehicle causing the glass to flex and crack. This, however, would not explain the starred windscreens or indeed the other evidence of impact that most people reported.

4. Stones on the road

An obvious explanation for the broken windscreens is that loose stones on the road were being flicked into the air by passing traffic and then impacting into the windscreens of other cars. This possibility was suggested right from the outset of the Esher incidents and was repeated many times by many different people. It is also clear that the local authorities favoured this theory when they sent a sweeper lorry to clear the Portsmouth Road, and that the police and Ministry of Transport, with their insistence that there was no evidence of malicious damage, also favoured an explanation along these lines. There is little doubt that flying stones can cause the kind of damage seen along the Portsmouth Road, but given the large number of incidents in such a short space of time, how likely is it?

When looking at the likelihood of stones being the cause of the Esher incidents, it is necessary to take a number of factors into account including the volume of traffic, the pattern of windscreen breakage and the type of glass used in cars of the day. We shall deal with these points individually.

i) Volume of traffic on the Portsmouth Road

During the early 1950s the Portsmouth Road (then the A3 road) was the major route for driving between London and south coast cities such as Portsmouth, Brighton and Southampton. It was therefore very busy indeed and the ENA had been campaigning for some time on the issue of traffic accidents and pollution through Esher itself, and with good cause (this is dealt with more fully in part three of this study). In September 1951 a census by the Automobile Association showed that there was an average of 987 cars an hour passing through Esher during the daytime, making that stretch of the Portsmouth Road officially Britain’s busiest highway. Allowing for slack periods at night, that would mean that around 12,000 to 15,000 vehicles a day passed through Esher town centre, a staggering number for an old Roman Road not designed for the purpose.

Given that somewhere in the region of 84,000 vehicles were travelling along the Portsmouth Road in a week, the occurrence of one or two stone-damaged windscreens does not make that look statistically unlikely. When one realises that during the three years in which the “phantom sniper” operated, something like over 12,000,000 cars must have travelled the road, then the 51 recorded damaged windscreens during this time actually looks statistically quite low (it equates to a 0.004% chance of a car along the Portsmouth Road being damaged during this time). In other words, the damage occurring to the windscreens is not that statistically unusual.

ii) Damaged windscreen statistics

There are statistics for everything in this world, including stone damage to windscreens. In 1998 Edgeguard International, an American glass manufacturer, undertook a survey of nearly 4,000 parked cars; 45% showed evidence of stone damage on their windscreen. This survey was backed up with another statistic which states that ‘stones cause 90% of windshield replacements’.

The seriousness of stone damage was also outlined in a report for the Ministry of Transportation and Highways of British Columbia, Canada, where loose aggregate on roads was causing a serious problem with broken and damaged windscreens. They recommended using smaller aggregate during their winter road gritting programme.

These results would appear to suggest that windscreen damage by loose stones is very common indeed with up to half of all cars showing evidence of stone damage. When these statistics are put together with the huge volume of traffic seen on the Portsmouth Road, the number of incidents again does not look statistically abnormal.

iii) Patterns of windscreen damage and windscreen type

One reason that the Esher incidents look so abnormal is because of the large number of windscreens that are not just chipped or starred, but actually shattered. According to the information given in the ENA and others, of the 51 damaged vehicles 32 actually had their windscreens completely destroyed. Although much was made of this destruction at the time, this may come down to the windscreen types being used in the 1950s.

Virtually all modern cars have laminated windscreens which have a thin layer of rubbery plastic sandwiched between two layers of glass. When hit by an object a laminated windscreen will not shatter or frost over, it will merely produce a spider-web pattern. However, laminated glass was only just coming into regular use in the early 1950s and a great many cars travelling along the Portsmouth Road would have had windscreens that were made of tempered glass which, when hit by an object, shatters into thousands of small pieces. It is this shattering that produces the characteristic ‘frosted over’ effect that can still be seen in broken side and rear windows of modern cars.

This difference in design leaves tempered glass more open to shattering than laminated glass. The fact that in the early 1950s tempered glass was more common than laminated glass would explain why so many windscreens were shattered. The glass type is only mentioned in two of the Esher incidents; both of these were laminated windscreens and both received only minor damage, not shattering which, whilst not conclusive, does follow the above pattern.

Further evidence in favour of loose stones comes from the pattern of the windscreen damage. For a start, most of the damage was to windscreens suggesting that the missile was coming towards the vehicle. Whilst a sniper could hit windscreens, it would be more likely that they would end up taking out side windows instead. Only one side shot was reported and that was the ‘bullet hole’ in Frank Smith’s car door. A second piece of evidence comes from the area in which the windscreen was hit. Of the four reports in which the area of impact is listed, all are on the driver’s side of the car. This is significant because stones flicked into the air are usually done so by traffic going in the opposite direction, which means that the stones are most liable to hit the driver’s side. However, stones lifted by a car in front can hit the windscreen anywhere at all.

The noise of a stone hitting a windscreen, from first-hand experience, is like a loud, sudden crack. Some people associated this noise with the shot of a gun, but given that the weapon most commonly cited was an airgun, and that the noise always came with the damage, this is again better evidence of a stone than a gunman. A shot would be expected to be heard after the damage if the shot came from some distance away.

It is also possible that there was something wrong with the road surface between Esher and Cobham which led to a greater than usual amount of loose stones on the road although, given the large volume of traffic, an abnormal road surface would not be necessary to produce the level of damage seen.

Conclusions

Given the evidence cited here we feel that at least the majority, if not all, the incidents along the Portsmouth Road can be explained by loose stones on the road being flicked into the path of other cars.

This might well explain what caused the physical damage to the cars but it does not offer an insight as to why the town of Esher acted in the way it did when faced with a few damaged windscreens. In the next issue we shall look for an explanation behind this episode of mass panic and look at other incidents round the world where broken windscreens have lead to civil unrest.