This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 22, Issue 4, from 2011

The Bible contains hidden messages which predicted the terrorist attacks of 11th September 2001, Barack Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize in 2009 and other historical events thousands of years before they actually happened. At any rate, this is claimed by the US author Michael Drosnin whose book The Bible Code became a bestseller worldwide in 1997 (Drosnin, 1997). According to Drosnin, it only takes arranging the letters of the Hebrew original text of the Bible in the right manner and the most interesting prophecies come to light.

The idea to search the Bible for hidden messages goes back to the Jewish Rabbi Chaim Weissmandl. In the 1940s, he searched the text of the Torah (which corresponds approximately to the Old Testament) for possible messages by forming so-called equidistant letter sequences. Such a sequence is formed when not all the letters of a text are looked at, but only every third or tenth or thousandth, and in this process blanks and punctuation marks are ignored. Usually a meaningless sequence of letters – which at best by chance contains a few meaningful words – is generated by means of this method. If, however, within an equidistant letter sequence several meaningful words turn up, which together make up a message, this suggests that the author deliberately encrypted a hidden message in the text.

The Rips code

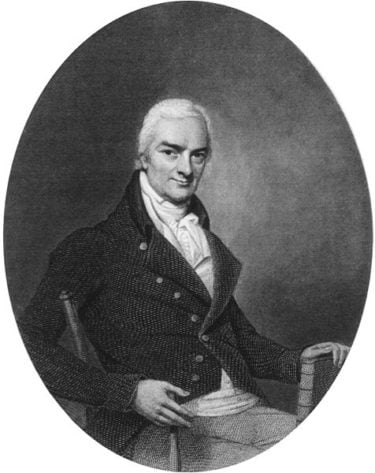

In the year 1983, the apparently positive results of Chaim Weissmandl inspired the Israeli mathematician Eliyahu Rips to occupy himself with the alleged codes in the Torah. Then as now, Rips was considered to be an ingenious mathematician, who has acquired an international reputation in the field of group theory. The believing Jew, who grew up in Latvia, had already revealed his mathematical talent in his younger days, but offended with his political views. In 1969, he was sent to prison after having attempted to set himself on fire as a demonstration against the intervention of Soviet troops in the Prague Spring. Even during his imprisonment, Rips made important mathematical discoveries. After heavy protests of Western mathematicians, Rips was released from prison and deported to Israel in 1972, where he continued his career.

In the course of his search for hidden messages in the Torah, Rips took a physicist named Doron Witztum as partner. After first analyses of equidistant letter sequences had rendered positive results, the two of them decided to search the Torah in this manner for the names of famous Jews and the dates of their birth and death. They wanted to know in how many cases a searched name turns up close to the respective date of birth or death. The laws of probability led them to expect a few hits. Rips and Witztum, however, hoped for a particularly high hit rate which would suggest that the Torah held an unknown code.

By means of a Jewish encyclopedia Rips and Witztum compiled the list of the searched names and dates. Overall, they included 66 Jewish celebrities each with his or her date of birth and death. Due to the fact that every Hebrew letter is assigned to a certain numerical value, they did not have to distinguish between numbers and letters. After this Rips and Witztum developed a statistical model. It defined a measure for the space between two character strings in an equidistant letter sequence. Moreover, it comprised a formula by means of which the arithmetic mean of several distances could be determined. The software for the execution of the search and the computation of distances and arithmetic means was contributed by the computer expert Yoav Rosenberg.

The result of the code search was astonishing: according to the calculations of Rips and Witztum the number of names and correct dates found seemed to be higher and the average distance between name and date of birth or death seemed to be significantly smaller than expected. This suggested that the author of the Torah had intentionally placed the names of the famous Jews including their dates of birth and death in the text. Due to the fact that all personalities in question only lived after the recording of the Torah, it did not seem possible to explain this result by scientific reasoning. Rips, Witztum and Rosenberg discussed their findings with other scientists. Several refinements of their search techniques supposedly did not change the surprising result.

Finally the three scientists submitted an article on their discoveries to the renowned professional journal Statistical Science. Since the specialized editors of this publication, too, did not find serious errors in the line of argument, the article “Equidistant letter sequences in the Book of Genesis” by Witztum, Rips, and Rosenberg (1994) was published in the journal Statistical Science. In this article the authors explained their statistical calculations and specified a significance level of 0.00002 for the small distances between name and date which they had discovered. This seemed to eliminate coincidence as an explanation.

From a topic for insiders to a bestseller

At first, the reactions to Rips’ supposed discovery of a Bible code were not so widespread as one would assume by hindsight. Most experts regarded the alleged Torah messages as a curiosity rather than as a serious field of activity. The public did not take much notice of the Rips code anyway. But this changed when the US journalist Michael Drosnin heard of Rips’ research. Before, Drosnin had worked as a reporter for the Washington Post and the Wall Street Journal and had published a successful biography of Howard Hughes entitled Citizen Hughes in 1987. The question of the Torah code fascinated Drosnin so much that he called on Eliyahu Rips in order to inform himself on the matter in detail.

In spite of his fascination, Michael Drosnin obviously did not consider it sufficiently spectacular that only some celebrities from the world of Jewry with their dates of birth and death could be found in the Torah. The US journalist therefore set to work himself, and scanned equidistant letter sequences from the Torah for further messages. In contrast to Rips, Drosnin dispensed with a scientifically exact approach, but – at his own discretion – searched instead for all kind of expressions which crossed his mind. With an appropriate variation of the search parameters he found something within the 304,805 letters of the Torah most of the time.

Like Rips did before, Drosnin also looked particularly for cases in which several meaningful words turn up close to each other within the tangle of equidistant letters. However, he did without the definition of a distance measure and similar mathematical sophistries. In this manner Drosnin hit, for example, on letter combinations which in Hebrew read as “Yitzhak Rabin” and “assassin will assassinate” and which, on top of that, intersect. The journalist interpreted this as an allusion to the murder of the Israeli Prime Minister Rabin in the year 1995.

Further ‘discoveries’ of this kind finally prompted Michael Drosnin to publish his book The Bible Code in 1997. In his book he reports on numerous alleged prophecies which his code brought to light. They refer to incidents and persons like Yitzhak Rabin, Winston Churchill, Stalin, Adolf Hitler, and Napoleon, as well as to other events in the history of the world. Moreover, Drosnin wrote that after the analysis of the biblical messages he had tried in vain to warn Yitzhak Rabin of the forthcoming assassination. However, this statement is not proven.

In his remarks Drosnin cunningly obliterated the fact that the alleged predictions on world history found by him did not have much to do with the work of Rips – neither with regard to the results nor with regard to the scientific level. Instead, Drosnin described Rips reverentially as hero and inventor of the Bible code and modestly took a back seat. This strategy, which was equally clever as it was bold, had the desired effect. The Bible Code became an international bestseller with 20 million copies sold worldwide.

The reactions

While many laymen took the code baubleries in Drosnin’s book at face value, experts only shook their heads. Statisticians and cryptologists agreed that with Drosnin’s method it was possible to find all kinds of messages in almost any book. In the case of the word “Rabin”, Drosnin chose an increment of 4,772, whereas it is entirely unclear for which other terms Drosnin searched the text and how high his hit rate was. As the author also counted words written backwards or diagonally, the hit rate was enhanced additionally. Last but not least, it was advantgageous for Drosnin that the original text of the Bible does not contain any vowels. Therefore the name “Yitzhak Rabin”, for example, consists only of eight letters. A further simplification results from the fact that Hebrew consists of only 22 letters. As each letter corresponds to a number, Drosnin also found many numbers referring to years in his equidistant sequences. Of course, the clever journalist made use of the fact that with an increment of one, numerous significant words inevitably will occur. By this method Drosnin found the expression “assassin will assassinate” – which is literally cited in the Bible (Deuteronomy 4:42).

Drosnin was not taken aback by such arguments. In the magazine Newsweek, he challenged his critics to find comparable messages in the text of Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick (Begley, 1997). If they succeeded in this, he argued, the randomness of the Bible code would be proven. The Australian mathematician Brendan McKay willingly accepted this challenge and demonstrated that it was possible to find would-be prophecies in Moby Dick. Although in contrast to Hebrew, in English the vowels are not missing, McKay detected the murders of Indira Gandhi, Leon Trotsky, Martin Luther King, and John F. Kennedy in the well-known whale story (McKay, 1997). Moreover, McKay came across the words “MDrosnin”, “nail”, “killed”, and “liar” which were close together (Drösser, 1997). Besides, together with the Australian telecaster John Safran, McKay found hidden messages in the lyrics of the rapper Vanilla Ice (Safran, 2004).

The US sceptic David E. Thomas also headed out to search for hidden pre-dictions. For the Skeptical Enquirer, he dealt with the King James version of the Old Testament and there came upon the word “Roswell” and the letters “UFO”. Furthermore, the physicist scanned the Book of Genesis, the English Bible, and a decision of the US Supreme Court for terms. Among other things he hit upon “comet”, “Hale”, “Bopp”, “died”, as well as “Los Alamos”, “atom”, and “bomb”. The name “Hitler”, too, together with “Nazi”, was among the hits in this text (Thomas, 1997).

The German sceptic organization GWUP also attended to the matter. In the year 1999 GWUP member Wolfgang Hund scanned the fairy tale “Rotkäppchen” (Little Red Riding Hood) and there ‘discovered’ a prophecy tailor-made for the mental magician Uri Geller: “Uri is in LA in March to meet US CIA men on old UFO”. Obviously, the Brothers Grimm at that time already knew of a meeting between Uri Geller and the CIA, and encoded this information in the form of an equidistant letter sequence in their fairy tale (Schmeh, 2006).

In the face of this state of affairs Drosnin was the subject of a series of malicious comments in the reputable media. “He who mines data may strike fool’s gold”, BusinessWeek said (Coy, 1997). The professional journal Cryptologia called the Bible code a “Leap of Faith based on fallacious mathematics” (Nichols, 1998). The German weekly journal Der Spiegel described Drosnin’s book as an “esoteric tome” and spoke of a “code without a future” (Der Spiegel, 1997). James Randi made the following remark: “The bottom line, of course, is that if you have a big enough text, and the ‘rules’ are as loose as they are, you can find ANYTHING you want” (Trull, 1997).

A scam that’s run its course

Of course, Eliyahu Rips also distanced himself from Drosnin’s book. He stated that he had not cooperated with Drosnin, that he did not support Drosnin’s reasoning, and that he considered the attempt futile to gather predictions from the Bible code (Rips, undated). However, all that did not bother Drosnin in the least. In the year 2002, he went one better with a further book which appeared under the title The Bible Code II: The Countdown (Drosnin, 2003). This work is hardly to be outdone in presumptuousness. Drosnin still does not discriminate between the Bible code described by himself and the work of Rips. The author does not waste one word on the criticism of his code fantasies, but solely responds to the criticism regarding the statements of the Israeli scientist. Of course, Drosnin also conceals that Rips had already distanced himself from Drosnin’s bestseller and instead once again presents the mathematician as his partner to whom he regularly talked over the telephone and whom he frequently went to see during his research.

With regard to contents the second Bible-code book offered little new information. Meanwhile Drosnin inevitably claimed to have also discovered the attacks on the World Trade Center in the year 2001 along with some other important events in world history in the Bible. The scientific level of the work again is bottom drawer. Thus the book neither contains mathematical nor statistical details. But Drosnin had apparently learned in the meantime what Nostradamus already knew: when making prophecies of world events one should not be stingy with horror scenarios. In The Bible Code II Drosnin therefore presents a coming “nuclear holocaust” for the year 2006 which explains the subtitle The Countdown. However, the aforementioned catastrophe has not yet not happened.

With his second Bible-code publication Drosnin found that his scam had run its course, as the sales figures of The Bible Code II fell short of its predecessor. But in the year 2003, another kind of honour was bestowed on Drosnin: he received an invitation from the US Department of Defense where intelligence staff interrogated him on the whereabouts of Osama Bin Laden. However, a suitable Bible passage for this extremely interesting question has not been found yet.

Already years ago, Drosnin advertised the third part, entitled The Bible Code III: The Quest. But the release was deferred repeatedly. The Neue Zürcher Zeitung did not refrain from offering critical words in advance: “To find the word pairs ‘too much’ and ‘fantasy’ in it [in the third Bible-Code book] will only be a question of assiduity and computing power.” (Schmitt, 2006). In October 2010, the book was finally published (Drosnin, 2010). The title had been changed to The Bible Code III: Saving the World. The content of this third Bible-Code work didn’t take anybody by surprise. Drosnin reports of additional prophecies he has allegedly discovered in the Bible. This time he found, among others, the elections of Barack Obama and David Cameron, the financial crisis of 2007, the Madoff scandal, and of course the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 – too bad none of these events had been mentioned in Drosnin’s second Bible code book (released in 2003). Another topic Drosnin continues in his new book is the warning of a global disaster (“atomic holocaust”). He does not waste much time explaining why such an apocalypse didn’t take place in 2006, which is what he predicted in the second Bible code book. Instead Drosnin describes a new scenario: an atomic terror attack, which might result in World War III. During all his code work Drosnin had Eliyahu Rips as an important partner – at least if Drosnin tells the truth. As Rips distanced himself from Drosnin years ago, such a partnership would certainly be a surprise.

It is quite obvious that Drosnin’s third attempt to make people believe in a Bible code has so far not been very successful. A Google search reveals that the media interest in the new book is almost non-existent. Amazon listed The Bible Code III at position 8,911 in the bestseller ranking (checked on November 30, 2010) with only 15 reviews. The first book of the series received 351 reviews.

Does at least the Rips code exist?

While the professional circles had only ridicule for Drosnin’s Bible code, the slightly less spectacular works of Rips and Witztum found considerably less opposition. Nevertheless, these works too encountered well-founded criticism. A publication of the already mentioned mathematician Brendan McKay and three other authors in the journal Statistical Science (McKay, Bar-Natan, Bar-Hillel, & Kalai, 1999) is considered as the most important work on this topic. First and foremost, the four scientists pointed out that the approach to code searching chosen by Rips and Witztum while appropriate was but only one of several possible alternative solutions. Regarding the selection of the Rabbis, Rips and Witztum took some liberties; the same applied to the spelling of the names, for which in almost every case there were several alternatives. With regard to the definition of the statistical model – particularly the distance dimension – there also was room for manoeuvre. Rips and Witztum could use this considerable leeway to choose the parameters in such a manner that the highest-possible hit rate would be achieved. The analyses of McKay and his colleagues actually showed that almost any other choice of parameters than Rips’ would have led to a less spectacular result. However, the experts around McKay avoided stating explicitly whether they thought Rips and Witztum had deliberately chosen favorable parameters or whether it was a coincidence or a mistake.

Apart from statistical arguments, McKay and his colleagues pointed out another problem: Rips and Witztum claimed to have conducted their experiments with the original text of the Torah – referring to the Koren edition published in 1962. But there are different versions of all Torah texts and therefore it is practically impossible to indicate an original text. The Koren version, for example, does not match in every detail with the scrolls from the Qumran caves which are considered as the oldest source of the Torah. It is obvious, though, that if the Bible code really existed, one single missing letter could suffice to make it collapse like a house of cards.

Further criticism followed. In the year 2003, the BBC produced a report on the Bible code in the course of which the Rips-Witztum experiment was repeated. This time the significance level was only between 0.3 and 0.5 – i.e., not statistically significant – instead of at 0.00002. Thus the “statistical proof of a miracle” (McKay et al., 1999) turned into a banality. It is not pure chance that the interest in the subject has decreased notably within the last few years.

Meanwhile, Rips added fuel to the fire with a new publication. In it, he claims that the Torah contains a code which alludes to the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in the year 2001 (Rips & Levitt, 2006). This statement was a surprise, because until then Rips’ code discoveries only referred to the names and dates of birth and death of important Jews. However, Rips’ new theory had little to do with Drosnin’s baubles, because the former is mathematically precise. Due to the fact that meanwhile the interest in the Bible code generally has decreased, there has not been much reaction to the new Rips code so far. It is quite striking that once again there are numerous code-search parameters which can be optimized in view of a most spectacular result. Thus, one may continue to entertain some doubts about the miracle.

In the end, the Bible code will probably rank among the long succession of other spectacular codes all of which probably only exist in the imagination. This includes, for instance, hidden messages in the works of Shakespeare which ‘prove’ that in fact they were composed by Francis Bacon (see Kahn,1996, for example). Further codes of this kind are allegedly to be found in the Koran, in the Egyptian pyramids, the Voynich manuscript, on the Shroud of Turin, in the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach, and in the Nazca geoglyphs – just to name the most important examples (Schmeh, 2008). Perhaps somebody will also scan this article for a code soon. There are certainly ample possibilities to find one.

References

- Begley, S. (1997). Seek and ye shall find. Newsweek, June 9.

- Coy, P. (1997). He who mines data may strike fool’s gold. Business Week, June 16.

- Der Spiegel (26/1997). Code ohne Zukunft.

- Drosnin, M. (1997). The Bible Code. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Drosnin, M. (2003). The Bible Code II: The Countdown. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Drosnin, M. (2010). The Bible Code III: The Quest. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Drösser, C. (1997). Wer suchet, der findet. Die Zeit, November 21.

- Kahn, D. (1996). The Codebreakers. New York: Scribner.

- McKay, B. (1997). Assassinations foretold in Moby Dick!

- McKay, B., Bar-Natan, D., Bar-Hillel, M., & Kalai, G. (1999). Solving the Bible Code puzzle. Statistical Science, 14, 150–173.

- Nichols, R. K. (1998). The Bible Code. Cryptologia, 22, 121–133.

- Rips, E. (undated). Public statement by Dr. Eliyahu Rips.

- Rips, E., & Levitt, A. (2006). The Twin Towers cluster in Torah Codes. The 18th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Hong Kong, 20–24 August 2006.

- Safran, J. (2004). John Safran vs God. Episode 7, SBS TV.

- Schmeh, K. (2006). Gibt es versteckte Botschaften in der Bibel? Skeptiker, 3, 88–91.

- Schmeh, K. (2008). Versteckte Botschaften; Die faszinierende Geschichte der Steganografie. Heidelberg: Dpunkt-Verlag.

- Schmitt, S. (2006). Merkel: Kanzler; Saddam: Knast. NZZ Folio 1.

- Thomas, D. D. (1997). Hidden Messages and the Bible Code. Skeptical Inquirer, 21(6), 30–36.

- Trull, D. (1997). Cracking “The Bible Code”.

- Witztum, D., Rips, E., & Rosenberg, Y. (1994). Equidistant letter sequences in the Book of Genesis. Statistical Science, 9, 429–438.