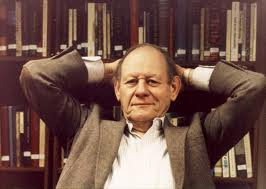

The following article is a press release from Prometheus Books, of which Kurtz was founder. Are more personal article was published by Kurtz’ former colleague , R Joseph Hoffman, on his blog. The photograph of Kurtz has also been reproduced from Hoffman’s blog.

The following article is a press release from Prometheus Books, of which Kurtz was founder. Are more personal article was published by Kurtz’ former colleague , R Joseph Hoffman, on his blog. The photograph of Kurtz has also been reproduced from Hoffman’s blog.

Paul Kurtz, philosopher, prolific author, publisher, and founder of several secular humanist institutions as well as the for-profit independent press Prometheus Books, died on Saturday, October 20, 2012 at his home in Amherst, New York. He was 86.

Professor Kurtz was widely heralded as the “father of secular humanism.” With his fifty plus books (many translated into foreign languages around the world), multitudinous media appearances and public lectures, and other vast and seminal accomplishments in the organized skeptic and humanist movements, he was certainly the most important secular voice of the second part of the 20th century. He was an ardent advocate for the secular and scientific worldview and a caring, ethical humanism as a key to the good life.

Kurtz was a professor of philosophy at the State University of New York at Buffalo from 1965 to his retirement in 1991 as professor emeritus. He founded the publishing company Prometheus Books in 1969, Skeptical Inquirer magazine and the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP) in 1976, Free Inquiry magazine and the Council for Secular Humanism in 1980, and the Center for Inquiry in 1991. Later projects included the launching of a scholarly journal, The Human Prospect, and a new nonprofit think tank, the Institute for Science and Human Values (both in 2010) where he served as chairman up until his death.

Paul Kurtz was born on December 21, 1925 in Newark, New Jersey. After graduating from high school he enrolled into Washington Square College at New York University, where he was elected freshman class president and became head of a student group called American Youth for Democracy. This was the beginning of his long romance with the power of ideas, but soon he would feel the call to serve his country.

Six months before his eighteenth birthday he enlisted in the army. In 1944 he and his unit found themselves smack in the middle of the Battle of the Bulge. Kurtz would later recall, “I was on the front lines for the rest of the war, in units liberating France, Belgium, Holland, and Czechoslovakia.” He entered both the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps shortly after they were liberated and met the survivors of Nazi brutality and their SS captors. It was an experience that would be seared in his memory for the rest of his life. Kurtz traveled with a copy of Plato’s Republic throughout the war, referring to it frequently during down times. His love of philosophy was becoming solidified during the most trying of times.

Upon the end of the war, Kurtz returned to the United States where he resumed his studies at New York University. It was there that he came face-to-face with the pragmatic naturalist Sidney Hook, the staunch anticommunist, humanist, and public philosopher who had studied himself under the leading American philosopher of the first part of the 20th century, John Dewey. Kurtz would later call this encounter “his most important intellectual experience.”

As “Dewey’s Bulldog,” Hook’s fierce commitment to democracy, humanism, secularism, and human rights exerted a powerful influence on the young student. Kurtz completed his undergraduate studies at NYU in 1948 and decided to continue his studies at Columbia University—where Dewey’s influence was even more palpable—but Hook and Kurtz would remain lifelong colleagues and friends. When Hook’s famous autobiography, Out of Step, was published in 1987, Hook sent a personal copy of the book to his former student with an inscription inside that read “Student, colleague, friend and co-worker in the vineyards in the struggle for a free society, who will carry the torch for the next generation.”

Kurtz went on to earn his MA and, in 1952, his PhD in philosophy at Columbia, where he studied under a group of distinguished professors—many of them former students of Dewey—and all scholars with sterling reputations of their own. The title of his dissertation was “The Problems of Value Theory.” His years at Columbia gave shape and definition to his life; he emerged from his rich educational experience as a philosopher firmly under the sway of pragmatic, naturalistic humanism. The upshot of this orientation was the abiding conviction that it was incumbent upon philosophers to descend from the isolation of the ivory tower and enter into the public arena where scientific and philosophical wisdom can be applied to the concrete moral and political problems of society at large and individual men and women engaged in the heat of life. This is the philosophical perspective that he would carry with him for the rest of his professional life.

Before settling at SUNY-Buffalo, Kurtz held academic positions at Trinity College in Connecticut (1952-59), Vassar College (1959-60), and Union College in Schenectady, New York 1960-65) during which time he also was a visiting lecturer at the New School for Social Research.

Kurtz was the editor of The Humanist magazine from 1967 to 1978 and was responsible for drafting Humanist Manifesto II, which was greeted with immediate enthusiasm upon its release in 1973. Endorsements rolled in from Sidney Hook, Isaac Asimov, Betty Friedan, Albert Ellis, B.F. Skinner, Maxine Greene, and James Farmer from the United States, and Nobel Prize–winner Francis Crick, Sir Julian Huxley, and A.J. Ayer from Great Britain. Altogether there were 275 signers. Humanist Manifesto II also became instant news, with a front-page story appearing in the New York Times, and articles in Le Monde in France and the London Times in Britain. An enduring phrase from that document stood as a clarion call to all clear thinking people that democratic, engaged, and responsible citizenship was needed like never before: “No deity will save us; we must save ourselves.”

The international skeptics movement got a lift in 1976 when Kurtz founded Skeptical Inquirer magazine. Concerned during the mid-1970s with the rampant growth of antiscience and pseudoscientific attitudes among the public at large, along with popular beliefs in astrology, faith healing, and claims of UFO and bigfoot sightings, Kurtz, along with fellow colleagues Martin Gardner and Joe Nickell, became a persistent foe of claptrap everywhere. As a critic of supernaturalism and the paranormal, he was consistently on the side of reason, always demanding evidence for extraordinary claims. It was during this period that Kurtz emerged in the public square as a stalwart proponent of the need for critical thinking in all areas of human life.

As a champion of many liberal causes during his lifetime, Kurtz became, during the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, an ardent supporter of women’s reproductive rights, voluntary euthanasia, the right to privacy, and the teaching of evolution in the public schools. And he was adamantly opposed to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or skin color. Yet Kurtz often found himself the target of both the extreme left and the extreme right, as his own critical and moderating intelligence often led him to embrace centrist positions on a variety of issues. He was a strong critic of supernaturalism and religious fundamentalism, but decidedly against the tone of the militant atheists.

During the student riots of the Vietnam era, Kurtz and his colleague Hook organized a moderate liberal-conservative coalition of faculty from across the New York state university system to oppose the often violent disruptions occurring on campus, as rebellious students set fires, blocked entrances to classrooms, and staged sit-ins. Kurtz found himself thrust into the middle of the drama and the spotlight, as SUNY-Buffalo became known as the “Berkeley of the East.” Kurtz’s battle against the mayhem made him a target of the student and faculty radicals. Soon he was being bitterly castigated as a “right-wing fascist” and “lackey of Kissinger, Nixon, and Rockefeller.”

But it was Kurtz’s deep involvement with the international humanist movement where his indelible mark will be felt for many years to come. Of all his contributions, it was his role as the leading intellectual and organizational figure in humanist and free-thought circles that he relished the most. It was the animating force of his prolific career. Bill Cooke, an intellectual historian, wrote in 2011: “Like Hook, Paul Kurtz has always been keen to distance humanism from dogmatic allies of whatever stripe. And like Dewey, Kurtz has wanted to emphasize the positive elements of humanism; its program for living rather than its record of accusations against religion. But it was Kurtz’s fate to be prominent at a time of resurgent fundamentalism.”

“Free Inquiry (magazine) was founded in 1980 at a time when secular humanism was under heavy attack in the United States from the so-called Moral Majority,” wrote Kurtz in 2000. His aims were twofold: by reaching out to the leaders of thought and opinion and the educated layperson, he sought to bring intellectual cachet and respectability to the philosophy of secular humanism while also forthrightly defending the scientific and secular viewpoint at a time when it was being demonized. The magazine grew to become a highly respected journal of secular humanist thought and opinion.

Kurtz was responsible for drafting four highly influential documents (“manifestos”) that served as guideposts for the secular movement from 1973 to 2010. These statements attracted the endorsement and support of many of the world’s most esteemed scientists and authors, including E.O. Wilson, Steve Allen, Rebecca Goldstein, Steven Pinker, Arthur Caplan, Richard Dawkins, Brand Blanshard, Ann Druyan, Walter Kaufmann, Daniel Dennett, Terry O’ Neill, Paul Boyer, Lawrence Krauss, James Randi, Patricia Schroeder, Carol Tavris, Jean-Claude Pecker, and many more. His last and most recent excursus was the Neo-Humanist Statement of Secular of Principles and Values (2010) a forward-thinking blueprint for bringing humanism far into the 21st century and beyond, emphasizing the need for a planetary consciousness and a shared, secular ethic that can cut across ideological and cultural divisions.

A genuine pioneer, Kurtz was always blazing new trails. He was the first humanist leader to call for and help implement a concerted worldwide effort to attract people of African descent to organized humanism. He helped establish African Americans for Humanism (AAH) in 1989. He was instrumental in helping to create and support, with Jim Christopher, Secular Organizations for Sobriety (SOS), a nonreligious support group for those struggling with alcohol and drug addiction.

Especially proud of his cosmopolitanism, Kurtz’s impact was truly global in scope. In 2001, he helped finance the first major humanist conference in sub-Saharan Africa (Nigeria). He helped establish humanist groups in thirty African nations, Egypt, Romania, and the Netherlands. He was so highly admired in India that he became virtually a household name.

Settling into his role as the elder statesman of a movement he saw take on wings around the world, he wrote, “Embracing humanism intellectually and emotionally can liberate you from the regnant spiritual theologies, mythologies that bind you and put you out of cognitive touch with the real world. By embracing the power of humanism, I submit, you can lead an enriched life that is filled with joyful exuberance, intrinsically meaningful and developed within shared moral communities.”

Kurtz’s joyful philosophy of life is presented in The Fullness of Life (1974) and Exuberance: A Philosophy of Happiness (1977). Of his many published works, the two he was perhaps most proud of are The Transcendental Temptation (1986) and The Courage to Become (1997). His core books on the importance of critical intelligence and the ethics of humanism include The New Skepticism: Inquiry and Reliable Knowledge” (1992); Living without Religion: Eupraxsophy (1994); and Forbidden Fruit: The Ethics of Secularism (2008). His primer What Is Secular Humanism? (2006) is about as cogent and clear an introduction to the topic as one can find. Meaning and Value in a Secular Age—a collection of his seminal writings about eupraxsophy—was published this year.

Kurtz is survived by his wife, Claudine Kurtz; son, Jonathan Kurtz, and daughter-in-law Gretchen Kurtz; daughters Valerie Fehrenback and Patricia Kurtz; daughter Anne Kurtz and son-in-law Jesse Showers; and five grandchildren, Jonathan, Taylor, and Cameron Kurtz, and Jonathan and Jacqueline Fehrenback.

The family has requested that gifts or donations in honor of Prof. Kurtz be given to the Institute for Science and Human Values. A public celebration of his life will be held at a future date.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was a very well-travelled eighteenth century aristocrat whose husband was appointed ambassador to Istanbul. Fortunately for us, she was also a prolific letter writer. Her legacy is still in print today.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was a very well-travelled eighteenth century aristocrat whose husband was appointed ambassador to Istanbul. Fortunately for us, she was also a prolific letter writer. Her legacy is still in print today.

The following article is a press release from

The following article is a press release from