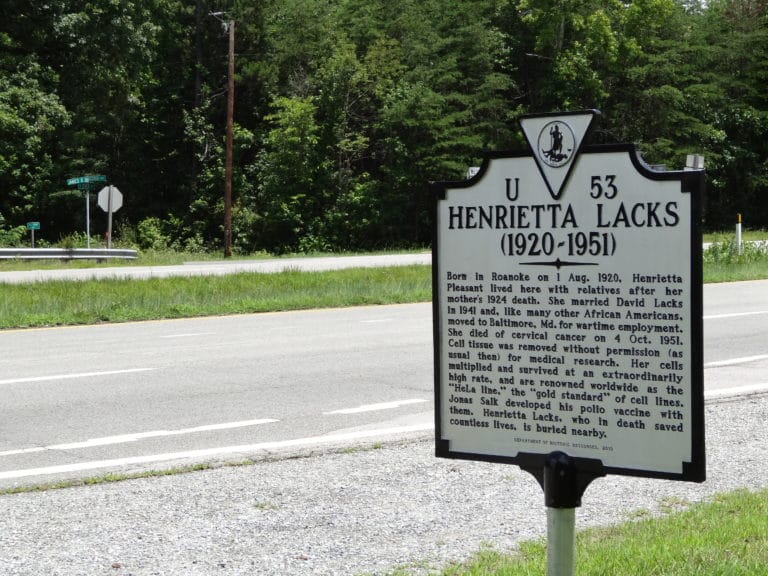

On the 29th January, 1951, a woman named Henrietta Lacks called into John Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, complaining that she felt a ‘knot’ in her womb.

Henrietta was a descendant of slaves and slaveholders, growing up farming the same land on which her forebears toiled, and that her relatives still farm today. She was the daughter of a poor tobacco farmer from Clover, Virginia. As part of an aspiring black middle class with rural roots, she left her childhood home to join a migration to Baltimore in 1941 with her husband and their two children, where her husband had a job as a steelworker. They had three more children, the last of whom, Joseph, was born at John Hopkins – the only hospital in the area that admitted black patients, in wards assigned for ‘Coloreds’. After Joseph’s birth, she suffered a severe haemorrhage, which prompted her visit back to the hospital because of the ‘knot’.

She was tested and a sample of a mass on her cervix was sent off for testing. The result of the biopsy showed she had a malignant epidermoid carcinoma (it later transpired she was misdiagnosed and actually had an adenocarcinoma, but the treatment would not have been different).

Henrietta was treated using radium tube inserts and discharged after a few days, with follow-up instructions to return for X-ray treatments. It was during her treatments that two samples of cells were removed from her cervix: one was a set of healthy cells, the other were from the tumour.

These cell samples were sent to one of John Hopkins’ cancer researchers, George Gey. He noticed that the cancerous cells exhibited unusual properties. Normally, cells cultured for laboratory analysis typically only survive a few days, which made it difficult to do multiple tests, as fresh samples would be required. Henrietta’s cells were different; they reproduced at a very high rate and could be kept alive almost indefinitely. This meant that many different tests could be done, without the need for multiple cell harvests.

Henrietta Lacks remained at John Hopkins until her death on the 4th October, 1951. During a partial autopsy, it was discovered that her cancer had metastasised throughout her entire body. She was buried in an unmarked grave in Lackstown, Virginia on land that was owned by slaveowners and later given to members of the Lacks family who were descendants of the slaves. Her exact burial site is unknown.

During her autopsy, one of Gey’s lab assistants, Mary Kubicek, was instructed to take further cells samples from Henrietta’s body, so that Gey could culture them for study. From these samples, he was able to start a cell line he named HeLa – Gey’s method of naming samples was to use the first two letters of a patient’s first and last names – a cell line that was effectively immortal, as the fast rate of reproduction and long life meant that they could be used, reproduced and studied indefinitely.

This was the first time that cells could be grown in a laboratory setting at a rapid rate – the first immortal cell line. As such, these cells were incredibly popular amongst researchers, as well as incredibly medically useful. In 1954, Jonas Salk used HeLa cells to help develop his polio vaccine. He also created the first ‘cell factory’, where HeLa cells were grown out on a production line in huge quantities. These cell samples were mailed out to researchers all over the world.

HeLa cells were used in some groundbreaking research, as well as some slightly more ethically dubious research – Chester Southam used HeLa cells to test if cancer could be transmitted by injecting them into prison inmates, as well as if you could use them as a type of cancer vaccine. They have been used for research into cancer, radiation, toxicity studies, and have been sent into space to test the effects of zero gravity on human cells.

George Gey, the researcher who originally took the cell samples, was a firm believer in confidentiality. The source of the HeLa cell line was kept secret until after his death in 1970.

In the early 1970’s, a large proportion of the HeLa cell line became contaminated by other cell cultures, so questions were asked about the original source of HeLa.

In 1975, after the providence of HeLa became known, Henrietta’s family began to receive requests for blood samples from researchers but had no idea why. It was only through a dinner party that they began to realise Henrietta’s role in scientific research 24 years after her cells had first been cultured, when a guest asked one of the Lacks family if they were related to the mother of the HeLa cell line. Henrietta’s close family had assumed that they might be being screened for cancer. However, this was an attempt to get a ‘clean’ sample of cells that might become another HeLa line.

The bounds of fairness, respect and courtesy had been breached in the case of the Lacks family. The gulf between them and the researchers – race, class and education – didn’t help matters. The researchers hadn’t offered any explanations.

The family were understandably both overwhelmed at finding out that Henrietta’s cells still lived and were being used for important scientific research, and furious that the original samples – as well as the samples taken during the autopsy – were taken without consent. When the family and wider black community found out about HeLa, it was seen as the case of a black woman whose body had been exploited by white scientists. Whilst John Hopkins never sold the HeLa cells, they have been used in commercial ways – cosmetic sensitivity testing, glue sensitivity testing, and other such tests. The original researchers may not have profited from HeLa, but others have. To date, over 11,000 patents originate from HeLa cells.

In the 1980’s, family medical records were published without consent and in 2013, researchers published the genome of HeLa cells; the family only discovered this when told by Rebecca Skloot, the author of a book about Henrietta. After complaints by the family, the genome was removed from public databases. Members of Henrietta’s family now sit on a committee that helps to oversee use of the HeLa genome. To date, none of the family have received any money from HeLa.

Until the Lacks family and the National Institutes of Health agreement, HeLa cells were considered to be ‘fair game’ – commercialised, bought, sold, had their genomes published and even used for some ethically dubious research. Under the new agreement, in part brokered by Rebecca Skloot on behalf of the family, the Lacks now have a say in how HeLa is used and what information on it can be made publicly accessible. Researchers who want to use the HeLa cell line have to agree to restrictions such as not sharing the genome information with others, reporting back on their results to the committee, and acknowledging the Lacks family in their publications.

It has also helped spark debate on ‘tissue rights’, especially amongst minorities; until relatively recently, courts have ruled that ‘discarded tissue’ was not the property of the donor, and could be used for commercial purposes. These days, people repeatedly ask if scientists or companies can commercialise cells or tissue, doesn’t the patient – as the provider of the raw material – deserve a say about it, and maybe a share of any profits that result? The forms given to people having surgery or biopsies usually spell out that tissue removed from them may be used for research. But patients today don’t really have any more control over removed body parts than Henrietta did. If your DNA or cells were used to create cures for diseases or used commercially, wouldn’t you at least want a say in how they’re used or a percentage of the profits generated?

Henrietta never knew her cells had been taken and died before the significance of her contribution to science, however unwitting, was known. Her legacy in the world of medical research cannot be overstated; to medical researchers, HeLa cells are as well known as lab coats, petri dishes and test tubes.

Henrietta Lacks may be the mother of the immortal cell line that bears her name and has made some people and companies very rich, but her name remains virtually unknown. Her family is not after fame or riches – they have never asked for money from the National Institutes of Health, just that her name is recognised and the hope that, in the future, people who have cell cultures taken might have a say in how they’re used.

Her grave site is still unknown, although a spot close to where her mother is buried, which is believed to be her resting place, only got a headstone in 2010 which was donated by Roland Pattillo, a faculty member of the Morehouse School of Medicine, a colleague of George Gey and friend of the Lacks family.

The donated headstone reads:

Henrietta Lacks, August 1, 1920 – October 4, 1951

In loving memory of a phenomenal woman, wife and mother who touched the lives of many.

Here lies Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal cells will continue to help mankind forever.

Eternal Love and Admiration, From Your Family

Mark Duwe is a web-designer who works mostly in advertising, but he also teaches astronomy in evening class. He’s a qualified homeopath (he didn’t take the final exam and passed with flying colours) and thinks reality is good enough without having to invent stuff.