Natasha Byrne investigates the role of a very modern medium in the proliferation of a very modern condition

It’s enough to make your skin crawl: relentlessly itchy skin, insect-like crawling and biting sensations, coloured fibres sprouting from open weeping sores and debilitating ‘brain fog’. Sound like science fiction? Not to over 14,000 families worldwide (Savely & Stricker, 2010) who have claimed to suffer from the controversial disease of ‘Morgellons’ – a highly distressing condition with strange symptoms and, as yet, an unknown cause. Many sufferers believe that they are infected with a mysterious parasite but other speculations range from alien creatures, bio-terrorism and nanotechnology to a by-product of genetically modified food. However, much of the medical community dispute that Morgellons exists at all and point to a diagnosis of Delusional Parasitosis (DP): a psychiatric condition where sufferers believe they are infested by organisms that are not actually there (Gieler & Harth, 2008). So if Morgellons really is a delusion rather than a parasite, then does that mean that delusions can be infectious?

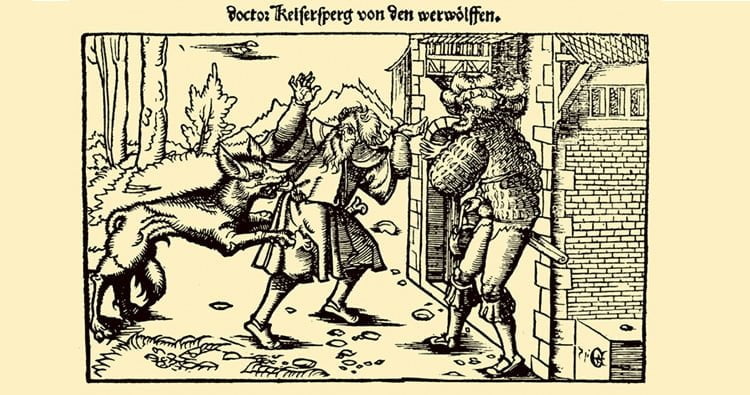

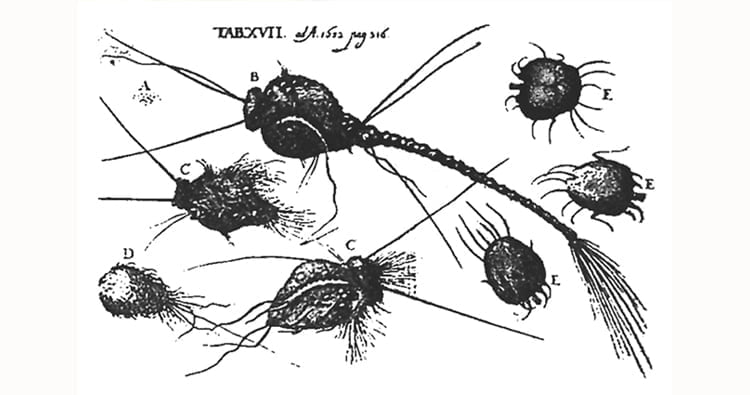

In 2001, Mary Leitao became concerned when her young son developed sores around his mouth that felt like they were crawling with bugs. On closer inspection with a toy microscope, she was astonished to find strange coloured fibres that appeared to be emerging from his wounds. Taking her son to several doctors, alarm bells began to ring for Leitao when not one would believe that there was anything unusual about his condition, telling her repeatedly that the ‘fibres’ must have come from their clothes (DeVita-Raeburn 2007; Elkan, 2007). Determined to find an answer, Leitao searched the internet and found an historical account of a peculiar disease. ‘Morgellons’ was first described in the 1670s by an English physician, Sir Thomas Brown, when he observed strange dark hairs sprouting from the backs of young children. These were later drawn by Dr. Michel Etmuller as a type of parasite with long tails (Kellett, 1935). Leitao felt sure that this is what had afflicted her son and so established the Morgellons Research Fund (MRF; no longer active) and website to research the disease, fight for recognition, and serve as a register for those who also believed they had the mysterious disease.

The plight of Morgellons sufferers caught the attention of the media when a pharmacologist, Randy Wymore and a paediatrician, Rhonda Casey, analysed fibre specimens from a Morgellons patient and failed to match them to any common environmental substances (Elkan, 2007). Thousands of registrations to the MRF followed the media coverage, mostly from California, Florida and Texas but also in all US states and 45 countries worldwide. Sufferers usually report open and slow healing skin lesions, intense itchiness and sensations of crawling insects, as well as the presence of coloured fibres or granules protruding from their sores (Fair, 2010). Other common symptoms include joint and muscle pain, sleep disturbances and cognitive impairment known by the community as ‘brain fog’ (Savely et al, 2006).

Growing media interest and a proliferation of the condition prompted some research, but studies produced ambiguous results. A study by Virginia Savely and Raphael Stricker (2010) found an unusually high number of tick-borne diseases in a sample of 122 Morgellons patients and 96.8% tested positive or suspect for Lymes disease, a bacterial infection. Conversely, a report on the MRF website (Stricker, Savely, Zaltsman & Citovsky, 2007) indicated that Argobacterium, bacteria used for making genetically modified crops, was present in skin samples from five patients but not in samples from controls. Another researcher found that DNA from one individual’s fibres matched a strain of fungus (Kilani, 2002).

Speculation from the Morgellons community is rife due to the inconsistencies of lab results and lack of appropriate treatment. Theories posted on online discussion boards include: parasites, “my suspicion is that this is a tiny nematode [flatworm] or similar bug which can live in the small intestine and also periodically moves to the skin” (posted by ‘jeanlong’, 2010); alien species, “These heavy chem trails [chemical trails deliberately sprayed by aircraft] may be dragging these ‘alien’ organisms down to Earth covering everything” (‘NotDelusional’, 2010); implanted nanotechnology, “I think we are being infested with ‘Smart Dust’ technology. It is being done so the whole world can be mapped out and surveiled (sic) 24/7 by those who have control issues” (‘terracer’, 2011); genetic modification, “I think it is possible that foreign DNA has entered the body through GM foods and agrobacterium” (‘2manyfibers’, 2009). The lack of thorough testing and government involvement in what many see as a frightening and debilitating condition has also sparked accusations of a government cover up. Such suspicions could be fuelled by the fact that the medical community remain largely sceptical about the legitimacy of Morgellons as a real disease and instead believe it to be a form of psychogenic illness.

The term psychogenic illness describes symptoms that are spread within a group that have no possible physical cause (Bartholemew & Muniratnam, 2011). In other words, the illness must be psychological. Indeed, many patients who believe they have Morgellons symptoms have been given the diagnosis of Delusional Parasitosis (DP) as the two conditions share some key characteristics (Savely & Stricker, 2010). Both involve an unwavering conviction that an organism has infected the body, despite lack of physical evidence, and attempts to extract it can result in self-inflicted skin damage (Gieler & Harth, 2008). However, the Morgellons community have fiercely rejected this label, possibly due to the stigma of a psychiatric diagnosis (Freudenreich et al, 2010). One group of researchers (Harvey et al, 2009) proposes some middle ground: the similarities to DP may suggest the two presentations are polar ends of the same broad disorder but with reversed cause and effect. Morgellons has (as yet unknown) physical causes that also produces psychological consequences, whereas DP is psychosomatic. Medical professionals attempting to treat Morgellons have had limited success, but recorded cases have shown improvement with hypnosis (Gartner, Dolan, Stanford, & Elkins, 2011) antipsychotic medication (Freudenreich et al, 2010; DeBonis & Pierre, 2011) and antibiotics (Harvey, 2007; Robles et al, 2008).

In 2008, increasing media attention and pressure from the Morgellons community prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) agency in the United States to fund a $500,000 clinical study to discover the cause of the mysterious symptoms. The results of the study were highly anticipated by the Morgellons community and many expected that they would finally get an explanation and validation of this strange condition. The long-awaited results were published early this year but were not what the community had been hoping for.

From the evaluation of 115 self-diagnosed Morgellons patients, Michele Pearson and colleagues (2012) could find no evidence of a new and distinct physical disease. They failed to find the presence of parasites or microbacteria and the majority of skin lesions examined were either consistent with insect bites, self-infliction or skin, or nerve conditions. Furthermore, fibre samples that were analysed were found to be environmental: the majority most likely from skin fragments or cotton. So, if there were no common physical signs of disease then were there any other shared characteristics that could account for the symptoms?

Drug testing showed that half of the sample tested positive for drug use. Formication (sensations of crawling under the skin) is a well-known side effect of drug use and withdrawal (e.g. ‘cocaine bugs’), which could explain some symptoms. Further to this, around 60% showed some cognitive impairment, 63% presented with clinical somatic complaints and 37% showed co-occurring psychiatric conditions. However, cause and effect relationships are not clear. Although the authors were careful not to rule out Morgellons as a new disease, they also did not reject the similarities to DP and suggested that patients may benefit from treatments that are effective for DP. So if Morgellons really is a delusion then how could it be spread to so many?

Delusions can be formed when ambiguous experiences are misinterpreted (Maher, 1974). Initially, sensations or experiences can become noticeable to the individual because of their intensity, because they cause distress or if they just won’t go away (Kirmayer & Sartorius, 2007). For DP patients, this could refer to a number of sensations such as skin irritation, dermatitis or insect bites as in the CDC study, or perhaps even just contact with something dirty. Attention can become biased toward these sensations and so excessive scrutiny is paid to any other ‘symptoms’ that may be related, such as peculiar markings on the skin. The stress of having strange symptoms or chronic irritation could also have physical effects (Kirmayer & Sartorius, 2007). These can include aches and pains, nausea, worsening of eczema and lethargy. The individual might then try to find an explanation for their experiences, but if the diagnosis given by a professional is not acceptable then they may look elsewhere… and where better to find information on obscure diseases than the internet?

Self-diagnosis from the internet is inherently problematic as information that is presented as fact is often not backed up with credible evidence. The internet can also act as a ‘carrier’ for spreading ideas and memes (an idea or concept that acts like a gene by being inherited, selected and mutated; Lustig et al, 2009; Freudenreich et al, 2010). In the case of Morgellons, it is possible that the internet had a key role in the spread of the condition and allowed one person’s delusion to develop into an outbreak.

Colligan and Murphy (1979, p.82) define mass psychogenic illness (MPI) as “the collective occurrence of a set of physical symptoms and related beliefs among two or more individuals in the absence of an identifiable pathogen”. Although MPIs are not common, there have been some well documented cases in recent history. For example, a rash of seizures amongst elementary school students in America was attributed to mass hysteria (Roach & Langley, 2002). On a wider scale, outbreaks of widespread Koro (unfounded fear of penis, vulva or nipple shrinkage resulting in death) have occurred in West Africa, China and South East Asia (Dzokoto & Adams, 2005). MPIs such as these often appear when there is mounting fear over terrorism, environmental contaminants or epidemics (Bartholomew & Muniratnam, 2011). This is reflective of the emergence of Morgellons, as there was a culture of fear after the 9/11 terrorist attacks as well as rising unease about GM food, chemical pollutants and vaccination scares. All of which had their own associated conspiracy theories and anti-authority movements. It has also been found that a local condition can develop into a MPI given widespread media attention (Dzokoto & Adams, 2005; Halvorson, Crooks, Lahart, & Farrell, 2008). With Morgellons, 75% of the symptoms in the CDC samples began to emerge on or after 2002; at the same time that the MRF and online community became established (Pearson et al., 2012). Undoubtedly, media attention brought the concept of Morgellons into the public’s awareness. From this, individuals who identified with the symptoms could reinforce their self-diagnosis through the social and group processes of the online community.

The internet allows individuals to connect with others who share the same experiences and also receive sympathy and validation of their problems. Once within a supportive community, group processes can abound where individual views are reinforced and exaggerated and the group consensus becomes increasingly polarised amongst pressure to subscribe to popular opinion (Turner & Pratkanis, 1998). Individuals may have to continually fight for public and medical acceptance of their condition and may rely on confirmation biases to do this. That is, accepting and presenting evidence that verifies their beliefs and discounting evidence to the contrary (Freeman et al, 2002). This could mean, for example, that any benign foreign materials that are present in lesions are counted as evidence of parasites or Morgellons fibres. Additionally, identifying as part of a group (e.g. the Morgellons community) may accentuate suspicions toward the motives of other ‘out’ groups (e.g. medical professionals; Tajfel, 1970) and create mistrust and breed conspiracy theories.

As well as social processes reinforcing delusions, many Morgellons discussions are focussed on encouraging rigorous cleaning or treatment rituals that may actually be detrimental to wellbeing and worsen symptoms. Suggestions for ‘treatment’ can include bathing with hydrogen peroxide, having a restricted diet and exhausting cleaning routines with other harsh chemicals. Furthermore, sufferers may isolate themselves for fear of ‘infecting’ others and become more dependent on the online community. Cycles such as this can lead to strong belief in the delusion and further deterioration (Kirmayer & Sartorius, 2007).

It is possible to see then, how someone may become ‘infected’ with Morgellons over the internet. The media exposure around Leitao’s interpretation of her sons condition could have presented a possible explanation for many individuals’ ambiguous symptoms. Searching Morgellons on the internet can then allow for hyper vigilance and confirmatory biases towards certain symptoms and inclusion into the supportive online community can validate self-diagnosis. Isolation, stress processes and following others suggestions of dubious home treatments could also worsen symptoms and create a cycle of dependence on the community, which may also result in a mistrust of dissenting medical professionals. All of these factors could account for a fixed delusion of infestation. However, it is also important to remember that current lack of evidence for a physical cause does not rule it out. There is the possibility that a proportion of Morgellons sufferers may actually have an unknown physical condition and experimental findings are being confounded by a larger majority experiencing an MPI.

So, beware. Next time you surf the net, you may get more that you bargained for…

Author

Natasha Byrne is a graduate from Goldsmiths University, currently working in a community mental health team.

References

2manyfibers (2009). Interesting Theorie. Retrieved 06/03/2012 from http://www.morgellons-disease-research.com/Morgellons-Message-Board/morgellons-theories-speculations/

Bartholomew, R.E., & Muniratnam, M. C. S. (2011). How Should Mental Health Professionals Respond to Outbreaks of Mass Psychogenic Illness? Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25(4), 235-240.

Colligan, M. J., & Murphy, L. R. (1979). Mass psychogenic illness in organizations?: An overview, Journal of Occupational Psychology, 52, 77-90.

DeBonis, K., & Pierre, J. M. (2011). Psychosis, Ivermectin toxicity, and “Morgellons disease”. Psychosomatics, 52(3), 295-6

DeVita-Raeburn, E. (2007) The Morgellons mystery, Psychology Today, 40(2), 96.

Dzokoto, V. A., & Adams, G. (2005). Understanding Genital-Shrinking Epidemics in West Africa: Koro, Juju, or Mass Psychogenic Illness? Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 29(1), 53-78

Elkan, D. (2007). The itch that won’t be scratched. New Scientist, 195 (2621), 46–9.

Fair, B. (2010). Morgellons: contested illness, diagnostic compromise and medicalisation. Sociology of health & illness, 32(4), 597-612.

Freeman, D., Garety, P. a, Kuipers, E., Fowler, D., & Bebbington, P. E. (2002). A cognitive model of persecutory delusions. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 41(4), 331-47.

Freudenreich, O., Kontos, N., Tranulis, C., & Cather, C. (2010). Morgellons Disease, or Antipsychotic-Responsive Delusional Parasitosis, in an HIV Patient: Beliefs in The Age of the Internet. Psychosomatics, 51(6), 453-457.

Gartner, A. M., Dolan, S. L., Stanford, M. S., & Elkins, G. R. (2011). Hypnosis in the treatment of Morgellons disease: a case study. The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 59(2), 242-9

Gieler, U., & Harth, W. (2008). Psychodermatology: The Mind and Skin Connection. American Family Physician, 59(4), 287-8.

Halvorson, H., Crooks, J., Lahart, D. A, & Farrell, K. P. (2008). An outbreak of itching in an elementary school-a case of mass psychogenic response. The Journal of School Health, 78(5), 294-7.

Harvey, W. T. (2007). Morgellons disease. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 56(4), 705-6.

Harvey, W. T., Bransfield, R. C., Mercer, D. E., Wright, A. J., Ricchi, R. M., & Leitao, M. M. (2009). Morgellons disease, illuminating an undefined illness: a case series. Journal of medical case reports, 3, 8243

jeanlong (2010). Morgellons Treatment. Retrieved 06/03/2012 from http://www.morgellons-disease-research.com/Morgellons-Message-Board/morgellons-treatment/

Kellett, C. (1935). Sir Thomas Browne and the Disease called the Morgellons. Annals of Medical History, 7, 467-479.

Kilani (2002). Investigation of Novel Organism Implicated in Morgellons Disease. Retrieved 31/01/2012 from http://www.morgellons.org/docs/clongen1.pdf

Kirmayer, L. J., & Sartorius, N. (2007). Cultural models and somatic syndromes. Psychosomatic medicine, 69(9), 832-40.

Lustig, A., Mackay, S., & Strauss, J. (2009). Morgellons disease as internet meme. Psychosomatics, 50(1), 90

Maher, B. A. (1974). Delusional thinking and perceptual disorder. Journal of Individual Psychology, 30(1), 98-113

NotDelusional (2010) ‘Upper Atmpsphere Bactrium and ???’. Retrieved 06/03/2012 from http://www.morgellons-disease-research.com/Morgellons-Message-Board/morgellons-theories-speculations/

Pearson, M. L., Selby, J. V., Katz, K. A., Cantrell, V., Braden, C. R., Parise, M. E. & Paddock, C. D., et al. (2012). Clinical, Epidemiologic, Histopathologic and Molecular Features of an Unexplained Dermopathy. PLoS ONE, 7(1)

Roach, E. S., & Langley, R. L. (2004). Episodic neurological dysfunction due to mass hysteria. Archives of Neurology, 61(8), 1269-72.

Robles, D. T., Romm, S., Combs, H., Olson, J., & Kirby, P. (2008, January). Delusional disorders in dermatology: a brief review. Dermatology Online Journal. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18713583

Savely, V. R., & Stricker, R. B. (2010). Morgellons disease: Analysis of a population with clinically confirmed microscopic subcutaneous fibers of unknown etiology. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology, 3, 67-78.

Savely, V. R., Leitao, M. M., & Stricker, R. B. (2006). The mystery of Morgellons disease: infection or delusion? American Journal of Clinical Dermatology, 7(1), 1-5.

Stricker, R.B., Savely, V.R., Zaltsman, A. & Citovsky, V. (n.d.) Contribution of Agrobacterium to Morgellons Disease. Retrieved 31/01/2012 from http://www.morgellons.org/suny.htm

Tajfel, H. (1970). Discrimination in Intergroup Experiments. Scientific American, 223, 96-102.

Terracer (2011). ‘Nano Sterility’. Retrieved 06/03/2012 from http://www.morgellons-disease-research.com/Morgellons-Message-Board/morgellons-theories-speculations/

Turner, M. E., & Pratkanis, A. R. (1998). Model of Groupthink. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 73, 210-235.

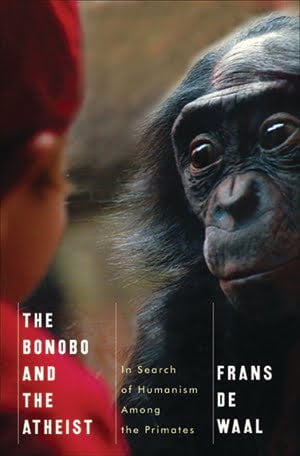

Is human nature a beast that needs to be tamed? Should we “throw out Darwinism in our social and political lives”? Or are we naturally altruistic, empathetic and moral?

Is human nature a beast that needs to be tamed? Should we “throw out Darwinism in our social and political lives”? Or are we naturally altruistic, empathetic and moral? For example, research has shown that moral decisions involve areas of the brain in humans and other animals that deal with emotions and – significantly – the evaluation of others’ emotions. Human morality is “firmly anchored in the social emotions, with empathy at its core” (De Waal,

For example, research has shown that moral decisions involve areas of the brain in humans and other animals that deal with emotions and – significantly – the evaluation of others’ emotions. Human morality is “firmly anchored in the social emotions, with empathy at its core” (De Waal,  The fact that it is social animals alone who display similar behaviour to ours is the key. It has been suggested by Dawkins that “humans are nicer than is good for our selfish genes”. But we give help roughly at the same level as we need it; tigers are solitary animals who neither need nor give help, for example. Behaving pro-socially makes society work and affords the benefits of social living to the individual.

The fact that it is social animals alone who display similar behaviour to ours is the key. It has been suggested by Dawkins that “humans are nicer than is good for our selfish genes”. But we give help roughly at the same level as we need it; tigers are solitary animals who neither need nor give help, for example. Behaving pro-socially makes society work and affords the benefits of social living to the individual. Tessa Kendall is a writer, researcher and campaigner, one of the organisers of London Skeptics in the Pub and Soho Skeptics.

Tessa Kendall is a writer, researcher and campaigner, one of the organisers of London Skeptics in the Pub and Soho Skeptics.

Noblett had been swimming across lake Windermere early one morning, accompanied by his colleague Andrew Tighe who was in a rowing boat when they report that a mysterious wave came out of nowhere, hitting both swimmer and boat. They both explained that there had been no boats on the lake prior to or during their journey, and that they hadn’t seen anything in the water as it passed behind them both.

Noblett had been swimming across lake Windermere early one morning, accompanied by his colleague Andrew Tighe who was in a rowing boat when they report that a mysterious wave came out of nowhere, hitting both swimmer and boat. They both explained that there had been no boats on the lake prior to or during their journey, and that they hadn’t seen anything in the water as it passed behind them both. When we left Windermere and headed towards Drumnadrochit in Scotland to begin our research into the Loch Ness Monster case, I thought we had left any mention of the wels catfish behind. Indeed the species of fish didn’t come up in conversation until the second day of our visit when Joe and I were sitting in the Loch-side home of Steve Feltham, who lives in his van on Dores Beach on a permanent look out for the Loch Ness Monster. He makes money by selling models of ‘Nessie’ to tourists (I have one sitting proudly on my desk). When you hear about Steve you would be inclined to think that he is on a fool’s errand, but once you meet him and start to listen to his story you realise that he is a man who has incredible insight into Loch Ness and the many mundane things that can, and are, mistaken for some sort of beast in the water.

When we left Windermere and headed towards Drumnadrochit in Scotland to begin our research into the Loch Ness Monster case, I thought we had left any mention of the wels catfish behind. Indeed the species of fish didn’t come up in conversation until the second day of our visit when Joe and I were sitting in the Loch-side home of Steve Feltham, who lives in his van on Dores Beach on a permanent look out for the Loch Ness Monster. He makes money by selling models of ‘Nessie’ to tourists (I have one sitting proudly on my desk). When you hear about Steve you would be inclined to think that he is on a fool’s errand, but once you meet him and start to listen to his story you realise that he is a man who has incredible insight into Loch Ness and the many mundane things that can, and are, mistaken for some sort of beast in the water.

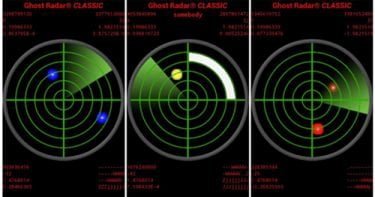

So, gone is the glass divination and in its place is the smartphone: it brings nothing new to the table. However, not only is this a biased and illogical method of investigation, it is also unfair and potentially misleading for those who’ve witnessed something they cannot explain, who have turned to the ghost hunters for help in the hope they can provide some extra insight. It’s fine, even if misguided, to sit at home and talk to ghosts through your smartphone apps, but I think it crosses a line when such techniques are used to offer answers to scared or desperate strangers in their own homes.

So, gone is the glass divination and in its place is the smartphone: it brings nothing new to the table. However, not only is this a biased and illogical method of investigation, it is also unfair and potentially misleading for those who’ve witnessed something they cannot explain, who have turned to the ghost hunters for help in the hope they can provide some extra insight. It’s fine, even if misguided, to sit at home and talk to ghosts through your smartphone apps, but I think it crosses a line when such techniques are used to offer answers to scared or desperate strangers in their own homes.