Hayley Stevens gets her smartphone out and goes ghost-hunting

Imagine the scene – a darkened room, the promise of ghosts. Only a candle illuminates the anxious faces of the ghost hunters seated around a table. The atmosphere is tense: “Are there any spirits?” one person asks tentatively. Silence falls for a few seconds and then comes the reply

“I found fifteen places matching ‘spirits’… nine of them are fairly close to you”.

A screen lights up on the table in front of them, and where traditionally a Ouija board and planchette may have sat; a list of locations helpfully compiled by Siri appears. Behold the modern era of ghost hunting, where the smartphone rules.

Admittedly, ghost hunters don’t actually use Siri to hunt for ghosts, but it’s not far from the reality. Modern ghost hunting has never really let go of its traditional roots of the Victorian Séance Parlours, and ghost hunters are often just upgraded Séance participants whose main aim is to talk to ghosts. The only thing that has changed is the medium they use to communicate with them. Traditionally, these were a table used during table tipping, a trance medium, or a Ouija board. Now it’s high-tech gadgets or, in more recent years, smartphone apps. Traditional methods are still often used, but the modern equivalents grow more and more popular every year, partially due to television shows that make ghost hunting with the gadgets and devices seem sexy and exciting.

The default functions of a smartphone can be useful – a torch, a compass, the camera and voice memos, for example. Yet there’s a whole range of specially designed ghost hunting apps just waiting to be downloaded by Zak Bagans wannabes everywhere. Some of them are even branded by popular ghost hunting television shows and advertised to fans at the end of each episode.

Most popular are those that take over the traditional role of gadgets in a ghost hunter’s arsenal. No longer do you need to carry around heavy flight cases full of different meters, dictaphones and photography equipment (with the hundreds of spare batteries and charger cables) when apps like ‘iEMF’ and the default voice-memos app will do the job just as well while being carried around in your pocket with just one cable. Need to set up motion sensors in a room to catch unseen intruders? No problem – there’s an app for that! Need to set up a ‘Trigger Object Experiment’ to see if an item left on its own will be moved by a ghost? Well you’re in luck because there’s an app for that too!

In Volume 23, Issue 2 of The Skeptic I reviewed an app called ‘Ghost Hunting Toolkit’ that offers numerous tools to aid you in your search for ghosts. From a vibration detector which detects whether an object is moving, or an interrogator that offers a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ button that a ghost can touch in response to your questions, to the power detector that requires the ghost to place its finger on the screen to detect how much energy it has – it’s difficult to tell if the developers are mocking the ghost hunters who buy it, or whether they’re dead serious with their claims.

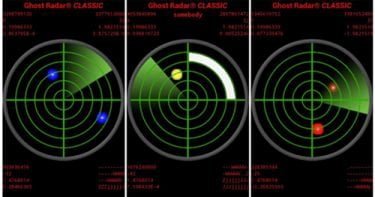

It gets weirder though. ‘Ghost Radar’ turns your phone into a sonar-like screen where blue, red and green dots appear at random to depict where spirits are in relation to you, and shows how strong their energy is. Stranger still is ‘iOvilus’, used to determine the messages ghosts are trying to communicate by reading slight fluctuations in the EM field. It corresponds these fluctuations with a dictionary of words “inputted by scientists” to reveal what the ghost is trying to say. The result is a list of random words spoken aloud by an electronic voice that the ghost hunters will often make fit with the spooky stories they’re dealing with. It’s a beautiful example of confirmation bias in action: believers ignore the words that don’t make sense, and go crazy for those that do, lauding them as evidence of a paranormal entity.

If there’s any doubt that such apps are actually used seriously during ghost hunts, a search for iOvilus or Ghost Radar on YouTube yields dozens of videos of them being used to detect and communicate with the dead.

Ghost detecting devices are often used in a similar fashion, and not as they’re designed to be. When EMF meters don’t find anything interesting they are turned into some sort of a planchette to be activated by the ghost in response to ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions. You might ask “Did you die here? Make the EMF meter light up for yes”, or “Is your name Elizabeth? Make the device beep to answer yes”. Similarly with torches, the battery cover is removed slightly causing the batteries to hardly touch the connector, and then questions are asked of the ghost in the anticipation they’ll turn the torch on and off in response. As you’d imagine, the battery occasionally touches the connector long enough to make the bulb light-up, and this is taken as a sign of spirit communication. As with the apps, the ghost hunters will often ignore the times the torch or EMF meter doesn’t respond in the way they’d like it to.

New technology is fun and exciting, but it will be apparent to The Skeptic readers that these ghost hunting devices and apps don’t make any progress in the field of paranormal research. In fact they simply make easier the use of pseudoscientific ideas that help ghost hunters with their biased approach to their cases.

So, gone is the glass divination and in its place is the smartphone: it brings nothing new to the table. However, not only is this a biased and illogical method of investigation, it is also unfair and potentially misleading for those who’ve witnessed something they cannot explain, who have turned to the ghost hunters for help in the hope they can provide some extra insight. It’s fine, even if misguided, to sit at home and talk to ghosts through your smartphone apps, but I think it crosses a line when such techniques are used to offer answers to scared or desperate strangers in their own homes.

So, gone is the glass divination and in its place is the smartphone: it brings nothing new to the table. However, not only is this a biased and illogical method of investigation, it is also unfair and potentially misleading for those who’ve witnessed something they cannot explain, who have turned to the ghost hunters for help in the hope they can provide some extra insight. It’s fine, even if misguided, to sit at home and talk to ghosts through your smartphone apps, but I think it crosses a line when such techniques are used to offer answers to scared or desperate strangers in their own homes.

The promotion of illogical ideas isn’t the only problem created by paranormal smartphone apps though. In 2012, there were international headlines from numerous ghost photos that were created using smartphone apps designed to help create hoax photos – from the ghost of Johnny Junior taken in someone’s front room in Gloucestershire1, to Jack, the Victorian gentleman photographed in the back garden of a family from Barnsley2.

Where hoax photos used to take some skill and time to set up and create, you now simply need an app and a photo upon which to add a ghost. Within minutes you can have a convincing ghost photo ready to prank your friends. There are similar apps for adding alien spaceships into your photos, and even apparitions of the Virgin Mary and Bigfoot too. Yet an increasing number of people are sending ghost photos created in this way to their local newspapers in alarm. The case of the Johnny Junior ghost photo in Gloucestershire is a great example of the harm that these sorts of apps can do.

A Cheltenham resident named John Gore contacted The Gloucestershire Echo to say that the ghost of a baby had been caught on a photo taken in his lounge. He told the paper:

“One of my cats kept scratching at the wall and jumping up in the area and we’re always taking pictures of the cats. When we got it through we were surprised to find the little figure just stood by the sofa. I have never really worried or had any ghost sightings before. We have had a few strange things happen before, like the TV kept changing channels and turning itself off.”

The paper ran the photo and the story, and it was instantly picked up by international news sources such as The Daily Mail and The Metro. There were problems with the photo though, the first being that the ghost in the photo was a fake created using an iPhone app which – having the same app – I recognised immediately. The second was that John Gore was associating the ghost in the photo with the death of a baby in the house a few years previously. He told the paper:

“I showed it to a lady over the road who has lived here for years. She said somebody who lived in the house before us had a child who died of cot death. It is hard to tell whether it is a boy or a girl, but we have called the ghost Jonny Junior, and it looks to be about a toddler’s age.”

With the speed at which the story spread it was extremely likely that the family who had lived in the house previously would read the story, see the address, and realise that it was allegedly their dead baby in the photo. With this in mind I phoned the journalist at The Gloucestershire Echo and explained how the photo had been created. Although she was resistant at first, I created a similar photo and sent it to her, at which she ran a follow-up story on the hoax. This resulted in an admittance of guilt from a friend of John Gore who had hoaxed the photo to prank his friend, but who had been too scared to admit to it after John Gore had gone to the press.

So we can see that it isn’t the apps themselves that pose a problem, but the context that they’re used in. A hoax photo intended to prank a friend going viral and making someone think that their deceased baby isn’t ‘at rest’ is problematic. Using ghost hunting apps in someone’s home and presenting them as a verified method of communicating with spirits is also a problem and poses numerous ethical implications, yet this is the reality we’re facing and there’s potential for it to get much, much worse.

Perhaps I am being dramatic when I envision the future of paranormal research being dominated with ghost hunters using their phones to first collect evidence of ghosts before then using their Wifi connection to upload it straight to their team websites, but the demand for new and more efficient ways to communicate with and capture evidence of ghosts is always growing, and the potential for new ghost hunting apps built up around nonsense ideas popular with ghost hunters is almost endless.

Perhaps someone will develop an app that enables ghost hunters to conduct experiments by filming television sets with their phones to see if they can capture ghostly faces? Or perhaps an app that enables you to join séances from a remote location? Or an automatic writing app that uses your touch screen keyboard instead of a pen?

Beware the app-aritions. They’re heeeere.

1 Johnny Junior – http://bit.ly/M0LkeO

2 Jack the Victorian Ghost – http://bit.ly/Mmpl2v

Hayley Stevens is a vocal skeptical paranormal researcher and has been actively investigating ghosts and monsters since her teens. She blogs at Hayley is a Ghost and The Heresy Club, and is a co-host for Be Reasonable, a podcast from the Merseyside Skeptics Society.