If we define ‘fake news’ as the presentation of a news story that is either known, by its author, to be evidently untrue; or not known, by its author, to be evidently true, we are referring to some long-practiced activities, older than the existence of commercial newspapers.

At its simplest, fake news involves an attempt to dishonestly convince a reader, viewer or listener of a claim about some aspect of their immediate reality, such as their healthcare or their politicians. But there is also a more complex form of fake news: an attempt to dishonestly convince a reader, viewer, or listener of a claim about a rival news source. As Donald Trump’s habit of accusing the journalists attending his own press briefings of being creators of ‘fake news’ (or, oddly, just ‘fake news’ itself) suggests, in the context of some public awareness that news fakery can happen, it is possible to convince the public to classify as fake all claims that come from a certain person, organisation, company or grouping. Indeed, it is possible to convince the public that everyone except a single news source is lying to them – a fundamental component of conspiracist thinking.

This second form of news fakery can be achieved by a process that involves the first: one can publish a whole contrived news story, attribute that news story to one’s adversary and then sit back to wait for someone to discover that the story is fake and observe smugly while one’s adversary is cancelled. But there is an even more efficient, and less risky, way of discrediting one’s adversaries: fake the very existence of the fake news story, by publishing what looks like public reactions to that non-existent news story rather than the story itself.

This practice makes it much harder for anyone to show that one’s target did not actually publish that news story, as it is always possible to insist that the original is unavailable for scrutiny not because it never existed but because of the ephemeral, messy and plethoric nature of works of news media. It is plausible to insist that the original fake news story cannot be found because it was published in the evening edition of a certain newspaper rather than its morning edition, or because someone has made a mistake about what day it was published or what newspaper it was published in, or because it was broadcast only on late-night news on terrestrial television in just one region, or because its authors have deleted it from their website.

An early instance, though probably not the earliest instance, of this second form of news fakery occurred in the American film industry in early 1910. At the beginning of 1910, the filmmaking industry in the US was divided into two factions: an older faction, the seven production companies (including the Edison Company) who had orchestrated the formation of the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC) in late 1908 in an attempt to use patents to monopolise the production, distribution and exhibition of films throughout the USA and Canada, and a younger faction, the six production companies, most of them set up by distribution companies who were trying to operate outside of the reach of the MPPC’s patents.

The ‘independent’ production companies and distribution companies had formed the National Independent Moving Picture Alliance in September 1909. One of these ‘independent’ distributors was the Laemmle Film Service, run by Carl Laemmle, who in June 1909 set up his own production company, initially called Yankee Films but soon re-branded as Independent Motion Pictures, or IMP. These ‘independents’ were trying to carve out a share of the market for hiring films to cinemas in the face of a system of licenses that the older faction was using to try to persuade cinema managers across the USA and Canada that getting their films from anywhere other than the MPPC was basically illegal. And in this situation of desperation, they were willing to try anything.

At the beginning of 1909 there was no star system in the film industry in the USA: when creating publicity posters for a film, for example, it was normal not to give the names of anyone who acted in the film; credits in films might indirectly name the director of the production company if that production company’s name was also the director’s name, but would not name any other people involved in making the film unless that person was, for example, a famous theatre celebrity appearing in a film on a short-term basis. But during the Summer and Autumn of 1909 Carl Laemmle, on a trip to Europe, probably saw some evidence of the Pathé Frères company launching a publicity campaign for a film actor, one Max Linder, and when he got back to the USA in mid-October 1909 he seems to have decided to do the same thing for one of his employees.

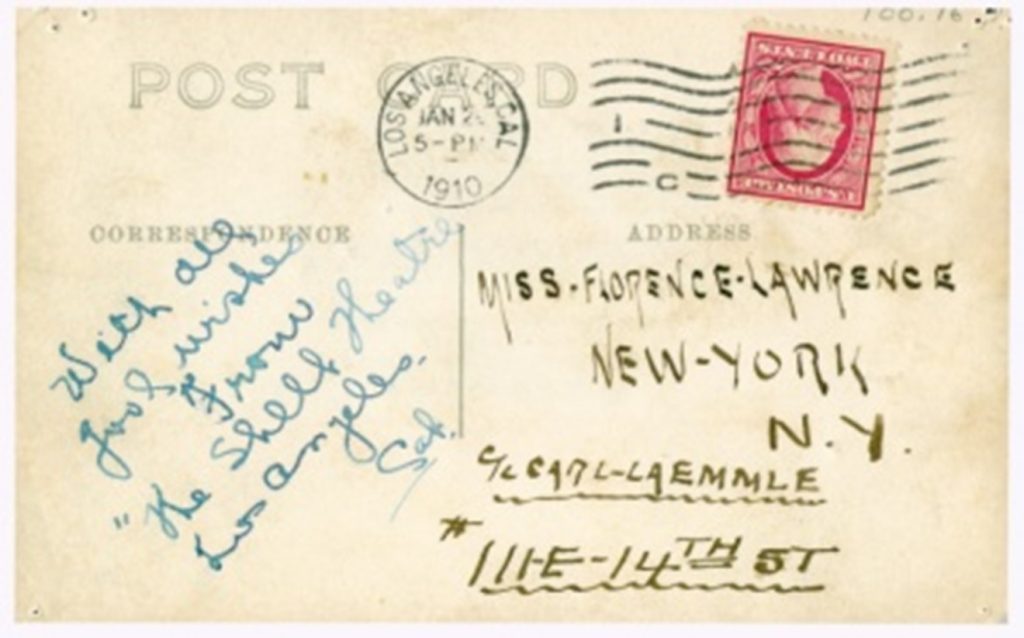

When Laemmle got back to the USA, he found that William Ranous, the director/producer who he had left in charge while he was away, had employed a new actress, a Canadian who was born Florence Bridgwood, who used the pseudonym Florence Lawrence, and who, significantly, had recently been fired by the Biography company, one of the members of the MPPC.

Florence Lawrence had accrued some recognisability during her time acting for films at Biograph, even though Biograph had never used her name in any publicity. That is, she was an asset that the older faction had somewhat short-sightedly thrown away. Finding that he now had such an asset on his hands, and willing to depart from the US industry’s norm of keeping film performers anonymous in publicity, Carl Laemmle jumped at the opportunity by launching a publicity campaign for her in which he used her name, in an attempt to gain an advantage over his rivals.

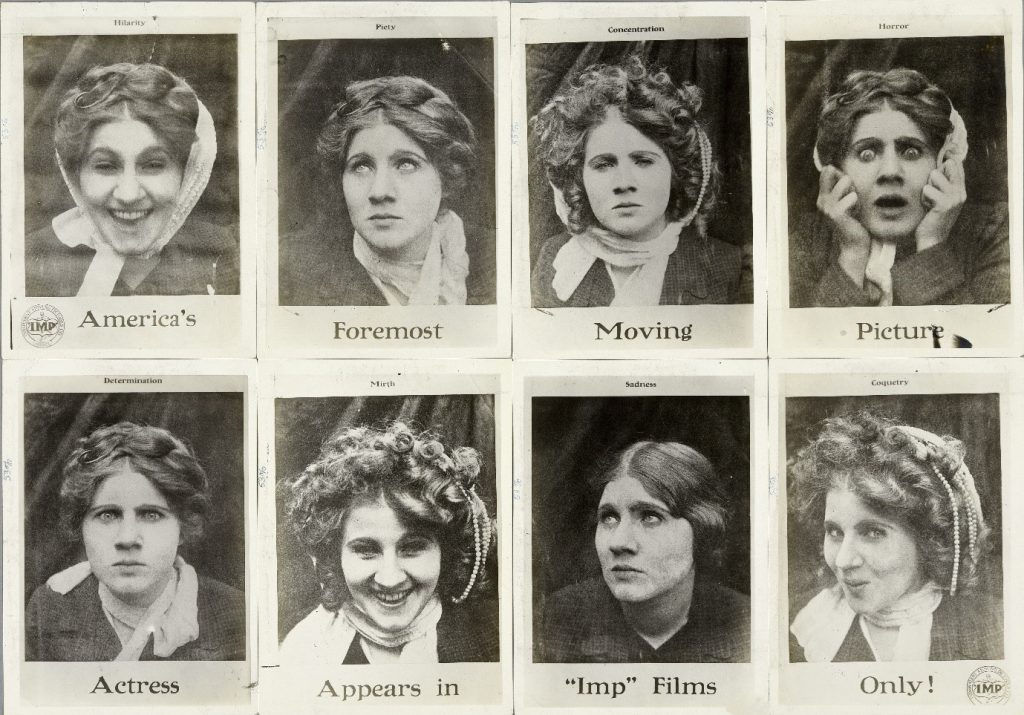

We can see evidence of this in a poster, dating from late January 1910, distributed by the Laemmle Film Service alongside Lawrence’s films, on display at a cinema in Los Angeles, a poster which refers to her as “America’s most popular moving picture actress”.

The eight photographs used on the poster have survived, and are reproduced below, with text under the photographs reading: “America’s Foremost Moving Picture Actress Appears in “Imp” Films Only!”.

Had Laemmle built Lawrence’s public profile and she didn’t agree to renew her contract when it expired in late 1910, Laemmle would have just built value in an asset that one of his rival companies could then use in competing against him. He therefore seems to have done everything he could to capitalise on Lawrence’s value during her time with him, including escalating this publicity campaign, and in collaboration with his press agent Robert Cochrane, he decided to use some second-order news fakery to do so.

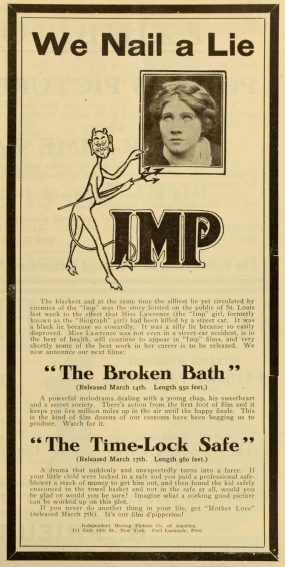

Reproduced here is an example of advertising that IMP placed in the film trade press in early March 1910.

Notice the opening text:

“The blackest and at the same time the silliest lie circulated by enemies of the “Imp” was the story foisted on the public of St. Louis last week to the effect that Miss Lawrence (the “Imp” girl, formerly known as the “Biograph” girl) had been killed by a street car. It was a black lie because so cowardly. It was a silly lie because so easily disproved. Miss Lawrence was not even in a street-car accident, is in the best of health, will continue to appear in “Imp” film, and very shortly some of the best work in her career is to be released.”

Before the publication of my 2019 book The Origins of the Film Star System, those film historians who have come across this advertisement in the trade press have got this story at least a bit wrong in a variety of ways, with some claiming that some St Louis newspapers published a news story which claimed that Florence Lawrence had died(1), and some claiming that no stories even mentioning the idea that Florence Lawerence had died had appeared in any St Louis newspapers(2).

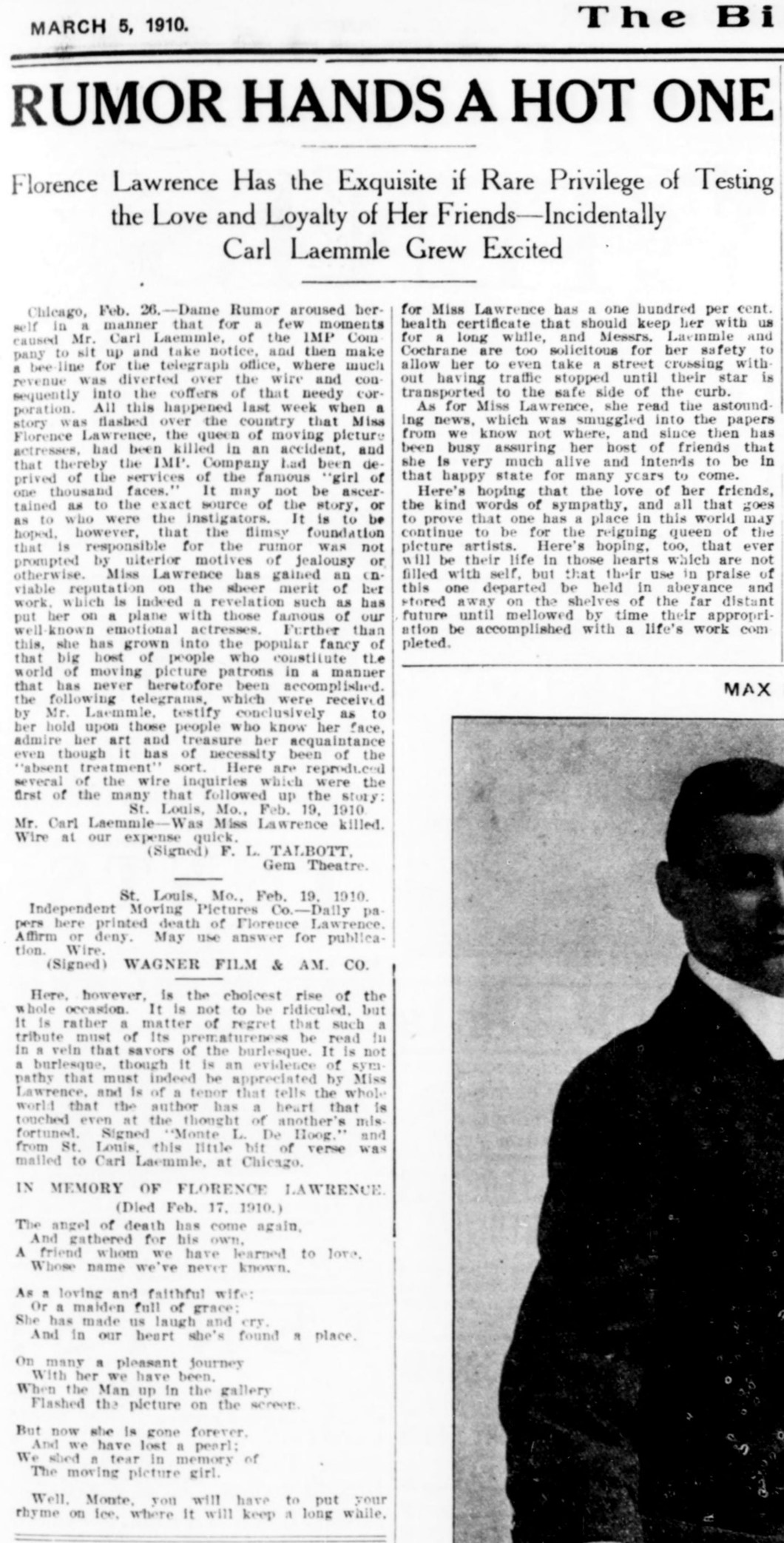

The truth is more complex, because some news stories were printed that referred to the belief that Florence Lawrence had died. The most elaborate of the surviving examples is reproduced and transcribed here, originally from Billboard in March 1910. To gloss some details: the Gem was one of St Louis’s independent cinemas, and the Wagner company was St Louis’s main independent film hiring company.

“Chicago, Feb. 26 – Dame Rumor aroused herself in a manner that for a few moments caused Mr. Carl Laemmle, of the IMP Company[,] to sit up and take notice, and then make a bee-line for the telegraph office [….] All this happened last week when a story was flashed over the country that Miss Florence Lawrence, the queen of moving picture actresses, had been killed in an accident, and that thereby the IMP Company had been deprived of the services of the famous “girl of one thousand faces.” It may not be ascertained as to the exact source of the story, or as to who were the instigators. It is to be hoped, however, that the flimsy foundation that is responsible for the rumor was not prompted by ulterior motives of jealousy or otherwise. Miss Lawrence has gained an enviable reputation on the sheer merit of her work, which is indeed a revelation such as has put her on a plane with those famous of our well-known emotional actresses. Further than this, she has grown into the popular fancy of that big host of people who constitute the world of moving picture patrons in a manner that has never heretofore been accomplished. [T]he following telegrams, which were received by Mr. Laemmle, testify conclusively as to her hold upon those people who know her face, admire her art and treasure her acquaintance even though it has of necessity been of the “absent treatment” [i.e. silent film] sort. Here are reproduced several of the wire inquiries which were the first of the many that followed up the story:

St Louis, Mo., Feb. 19, 1910

Mr Carl Laemmle – Was Miss Lawrence killed. Wire at our expense quick.

(Signed) F. L. TALBOTT.

Gem Theatre.

———

St. Louis, Mo., Feb. 19, 1910

Independent Moving Pictures Co. – Daily papers here printed death of Florence Lawrence. Affirm or deny. May use answer for publication. Wire.

(Signed) WAGNER FILM & AM. CO.

[…]

Signed “Monte L. De Hoog,” and from St. Louis, this little bit of verse was mailed to Carl Laemmle, at Chicago.

IN MEMORY OF FLORENCE LAWRENCE

(Died Feb. 17, 1910.)

The angel of death has come again

And gathered for his own,

A Friend whom we have learned to love,

Whose name we’ve never known

As a loving and faithful wife;

Or a maiden full of grace;

She had made us laugh and cry,

And in our heart she’s found a place

On many a pleasant journey

With her we have been,

When the Man up in the gallery

Flashed the picture on the screen

But now she is gone forever,

And we have lost a pearl:

We shed a tear in memory of

The moving picture girl.

Well, Monte, you will have to put your rhyme on ice, where it will keep a long while , for Miss Lawrence has a one hundred per cent. health certificate that should keep her with us for a long while, and Messrs. Laemmle and Cochrane are too solicitous for her safety to allow her to even take a street crossing without having traffic stopped until their star is transported to the safe side of the curb.

As for Miss Lawrence, she read the astounding news, which was smuggled into the papers from we know not where, and since then has been busy assuring her host of friends that she is very much alive and intends to be in that happy state for many years to come.

Here’s hoping that the love of her friends, the kind words of sympathy, and all that goes to prove that one has a place in this world may continue to be for the reigning queen of the picture artists. Here’s hoping, too, that ever will be their life in those hearts which are not filled with self, but that their use in praise of this one departed by held in abeyance and stored away on the shelves of the far distant future until mellowed by time their appropriation be accomplished with a life’s work completed.”

What is going on here? Of course, Carl Laemmle and Robert Cochrane are trying to make out that Lawrence Florence is much more famous and much more publicly adored than she actually is, as a way of trying to get the public to treat her as more famous than she actually is, which might in turn actually make her that famous.

Laemmle and Cochrane organised for Florence Lawrence to make a series of personal appearances, in the company of her fellow employee King Baggot in St Louis, Missouri on the weekend of 25th to 27th March 1910 (Baggot was a St Louis native), and Laemmle and Cochrane had probably already done so before creating this press release; these personal appearances both ‘responded’ to the non-existent public outcry about the news that she had died and created opportunities for further news stories about Lawrence being mobbed by fans. But in addition to this ‘fake it until you make it’ strategy, in this press release Laemmle and Cochrane are also orchestrating a piece of subtle second-order faking of fake news.

The press release claims that one of IMP’s competitors had published a fake news story about Florence Lawrence’s death, and its ‘evidence’ of this earlier fake news story takes the form of horrified responses to that news among residents of St Louis, both people who work in the film industry (the manager of the Gem and the manager of Wagner) and a member of the general public (the probably entirely invented ‘Monte L. De Hoog’). We can be very confident that no original news stories claiming that Florence Lawrence had died were ever published, but by faking these bits of evidence of a horrified reaction to such a story, IMP faked those original news stories indirectly. The staff at the IMP company did this both to try to discredit the MPPC companies by making them appear to have created a piece of fake news and to build the IMP company’s own reputation by making out that the IMP staff have heroically saved the public from an attempt to deceive them.

Billboard was reproducing most or all of IMP’s press release. Such press releases are designed to feed copy into national and local newspapers, and several local newspaper editors do seem to have been convinced by this claim that a story about Lawrence’s death had been printed somewhere, because versions of the story about the debunking of the fake news of Lawrence’s death appeared in some local Mid-West newspapers, including the St Louis Post-Dispatch on 6 March 1910(3), and on 7 March 1910 a contributor to Louisville’s Courier-Journal remarked that “it was only the other day that a report had gained wide credence that this charming actress had met with an accident while posing on the streets of New York”(4). That is, the attempt at discrediting IMP’s business rivals, without even naming them, met with some success.

In early 1910, then, in the era of print newspapers, we can identify industry awareness of some basic guidelines for how to conduct news fakery in the context of the public awareness that news fakery can happen:

- Do not actually directly fake the news. To do so means there could be a paper trail that might lead to you. Instead, print a third-hand ‘account’ of the fake news in the form of a report of people who have supposedly read/seen/heard that original news story.

- Attribute the act of hearing the fake news to a reputable source, so you can say that you have it on good authority that the lie existed.

- Avoid naming the people who are supposedly responsible for the fake news, but nonetheless imply their identity.

- Make the claims in the third-hand fakery both a) perverse, and b) imbecilic in their susceptibility to being shown to be incorrect.

- Make the claims in the third-hand fakery amenable to an act of refutation that serves one’s own interests (in Laemmle’s case, the announcement that as Lawrence was luckily not dead, it was incumbent on IMP to announce which films the public might see her in next).

This act of covertly faking a piece of covert-turned-exposed fake news and attributing that act of fakery to one’s opponent was a straightforward consequence of a highly competitive business environment, itself a product of the little-regulated form of capitalism that was practised in the USA at the time. (I say ‘little-regulated’, as anti-trust legislation did exist in the USA: with reference to the prohibitions against a monopoly that had been stated in the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890, decisions in several cases concerning the MPPC, at District Court level, Circuit Court level and Supreme Court level, in late 1915 through to early 1918, resulted in the MPPC’s dissolution, in spite of the argument that its pool of patents exceptionally gave it the right to control trade in and use of films in the USA.)

Fostering unwarranted public mistrust of one’s competitors is one natural consequence of any system that makes competition the crux of how humans interact with each other. Unwarranted public mistrust of anyone and everyone except for a single source of ‘information’ is one of the two fundamental components of the mindset behind conspiracy theorising (the other is a lowering of the burden of proof for that single source of ‘information’). Our habits of thought are shaped by large-scale systems to which we have grown so accustomed that we cannot even see them as systems anymore. With a knowledge of what capitalism prompts its subjects to do to each other, we should not be surprised at just how widespread that public mistrust and its resulting conspiracism currently is.

Footnotes

(1) Anon., ‘Heroes and Heroines of Moving Picture Shows’, St Louis Post-Dispatch Sunday Magazine, 6 March 1910, p. 4. Anon., ‘Famous Picture Actress is Still in Posing Land’, Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky) 113.15040 (6 March 1910), section 4, p. 8; this article included two of the eight ‘range photographs and claimed that the fake obituaries had been printed on 4 March 1910.

(2) Anon., ‘Love Picture and Two Star Comics’, Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky) 113.15041 (7 March 1910), p. 10.

(3) See, for example, Ralph Cassady, ‘Monopoly in Motion Picture Production and Distribution,’ 1959, The American Movie Industry: The Business of Motion Pictures, ed. Gorham Kindem (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1982, pp. 25-68, p. 52, Richard Schickel, The Stars (New York: Bonanza, 1962), p. 11, Alexander Walker, Stardom: The Hollywood Phenomenon (New York; Stein & Day, 1970), p. 31-2, Kevin Brownlow, Hollywood: The Pioneers (London: Collins, 1979), p. 156, Charles Musser, ‘The Changing Status of the Actor’, Before Hollywood: Turn-of-the Century American Film (New York: Hudson Hills Press/American Federation of Arts, 1987), pp. 57–62, p. 59, Richard Dyer MacCann, ‘Early Luminaries’, The Stars Appear, ed. Richard Dyer MacCann (Metuchen: Scarecrow, 1992), pp. 44-47, p. 45, Eileen Bowser, The Transformation of Cinema, 1907-1915 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), p. 112, Hugues Marc Antoine Bartoli, ‘Florence Lawrence: Myth and Legend of the Biograph Girl’, Classic Images 343 (January 2004), pp. 71-6, p. 73, Robert Kobel, Silent Movies: The Birth of Film to the Triumph of Movie Culture (London: Little, Brown & Co., 2007), p. 151, Richard Abel, Americanizing the Movies and “Movie-Mad” Audiences (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), p. 232.

(4) This has been the case for most (but not all) film historians who have written on the topic since Richard deCordova, Picture Personalities, 1990 (Champaign, Ill: University of Illinois Press, 2001), p. 58.