This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 4, Issue 3, from 1990.

They cannot destroy fairies by antediluvian tests, and when once fairies are admitted other psychic phenomena will find a more ready acceptance.

– from a letter to Edward L. Gardner from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 21 October 1 920.

The normal attitude of establishment science to such nonsense and the damaging effect it can have on the popular understanding of science is one of studied academic disdain. But occasionally, very occasionally, a major scientific or public institution makes a stand against pseudoscientific nonsense.

A few years ago the Natural History Museum featured a small gallery display entitled ‘The Feathers Fly’, which questioned Sir Fred Hoyle’s authority on evolution and in particular paleontology. Sir Fred and friends, who had put forward the notion that the famous intermediate reptile/bird fossil Archaeopteryx was a fake, have kept their heads below the parapets ever since.

A new exhibition at the British Museum, which runs until September 1990, is much larger and tackles a much broader spectrum of – this time – real fakes. Although it is primarily concerned with artistic and antiquarian fakery, there is much of interest to the student of scientific pathology. There is a potted history of faking, from pieces of the ‘true cross’ to the Cottingley ‘fairies’ photographs, a section on dating and detecting fakes and a look at some still problematic artifacts.

The first section of interest, section three of the exhibition and the catalogue, is entitled ‘The limits of belief: religion, magic, myth and science’. In it we are treated to a potpourri of the real outer limits of belief. Faked letters purportedly from J.C. himself, but Anglo-Saxon or Medieval concoctions, sought to provide extra Biblical ‘evidence’ for his curative powers and his gentile appearance. Reliquary pendants containing bits of saints, pieces of the true Cross and drops of the milk of the Virgin Mary launch us into a weird world of mythical beasts and alchemical transmutations. Griffin’s claws (ibex horns), Mermen (half fish and half monkey) and Sea Bishops (contorted Skates) lie alongside an iron knife with a golden tip.

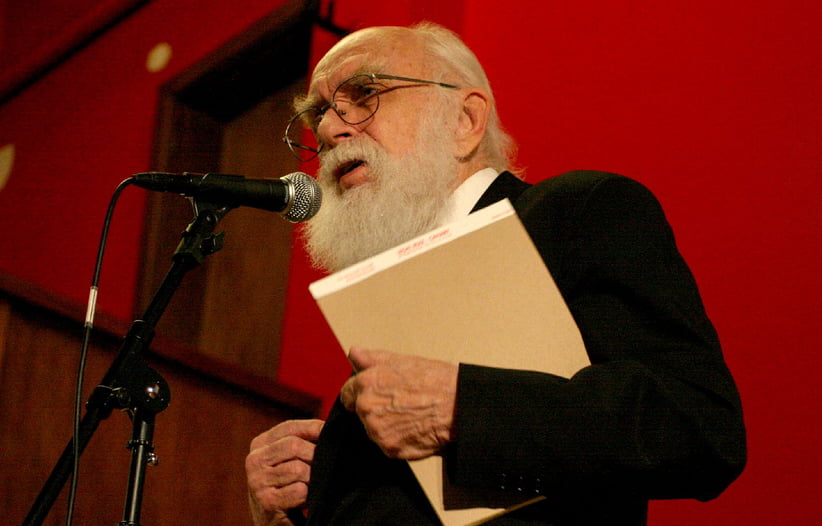

An early James Randi noted ‘the Imposter with legerdemain trick, changing the plain knife, after its dipping, deceived the Eyes of his nimble motion, and brought forth the other with the Gold Blade; then again the Great Elixer being spilt on the ground, and pretended could never be made again… (it was) purchased by the late possessor, at a very considerable price.’

These lead on to more ‘scientific’ frauds. The carved fossils used to hoax Professor Beringer of Wurzburg in the early sixteenth century. The penny didn’t drop until he saw his own name in one of the fossils. He then tried to buy up all the copies of his monograph on them. The same cannot be said of Conan Doyle who seems to have gone to his grave believing in the cut-out fairies of a pair of young Yorkshire lasses. This display could have been improved if a copy of Princess Mary’s Gift Book from which the cut-outs were taken had been included.

The famous Piltdown Man hoax must, however, take pride of place in this section. The original skull fragments are on display as well as the associated fauna and artefacts, including the carved bone ‘cricket bat’! This must have been the real clincher that the British Piltdown Man was higher up the evolutionary scale than the continental Neanderthalers or Heidelberg Man. The discoverer, Charles Dawson, has always fallen under suspicion as the perpetrator, but there have always been other likely candidates and motives galore. However, further exhibits point the finger at Dawson as an inveterate local hoaxer.

It was a revelation to me that the infamous ‘Toad in the Hole’ (PG Tips Unexplained Mysteries of the World No.4) was communicated by the same Charles Dawson to the Brighton and Hove Natural History and Philosophical Society in 1901, 11 years before he announced Piltdown Man. Other ‘finds’ of Dawson’s have since been proved to be fakes. These include a supposed Roman cast-iron statuette (now considered 19th century), stamped Roman tiles from Pevensey Castle (early 20th century fakes), a Norman prick spur (no such thing says the BM) and a prehistoric hammer made from a recent Red deer antler. ‘Say no more’ as the saying goes.

The next section of interest to readers of the Skeptic is section 9: ‘The scientific detection of fakes and forgeries’. This has interesting examples of the techniques of ultraviolet and X-ray radiography, mass spectrometry and thermoluminescence as well as various dating methods. Central to the latter is the Turin Shroud. This is on display as a very effective life-size transparency, but although the accompanying caption states that the carbon-14 date is definitely AD 1260-1390 it pulls back from a definitive trouncing of the shroud by ending on a note of compromise: ‘However, until it can be properly established how this striking image came into being, the mystery remains incompletely resolved.’

The final section, ‘The limits of expertise’ looks at some tantalising examples of where the experts agree to differ. The Vinland map, The Grime’s Graves female figurine and phallus and the ‘Aztec’ rock-crystal skull (PG Tips 23) which, although the teeth seem to have been incised by a jeweller’s wheel is still on the ‘problematic’ list.

Fake? The Art of Deception was an exhibition at the British Museum, Great Russell St, London WC 1, from 9 March to 2 September 1990. Admission £3, concessions £2. exhibition catalogue £16.95.