Note – contains references to sexual assaults

This story was originally written in Portuguese, and published to the website of Revista Questão de Ciência. It appears here with permission.

Between the 1950s and 1980s, a group of people in New York City decided to abandon monogamy and the traditional notion of family. Women who wanted to have children were encouraged to have sex with a large number of partners, in order to obscure the identity of the parents as much as possible. Couples who were too attached and who preferred to have sex only with each other were warned and criticised. Children were raised communally and, preferably, as far away from their biological parents as possible.

At first, this alternative model of life was adopted and maintained more or less freely and voluntarily. However, as time went by and charisma and power became increasingly concentrated in the hands of the leader, the psychological and emotional pressure to obey and conform to the group’s rules took on an increasingly authoritarian tone.

The leadership began to claim responsibility for authorising (or not) members to have children; women who refused to have sex with any member of the community on request (and especially with the leader) were ostracised. One reticent girl was told: “Shut your mouth and spread your legs.”

The members led normal lives during the day – doctors, lawyers, artists, writers – but at night they returned to the collective’s communal apartments. In these environments, deviations from the group’s norms and expectations were recorded and pointed out by informants. Delinquents ran the risk of public humiliation or expulsion.

It sounds like a religious cult… but it was ‘psychotherapy’. The community was made up of patients, students and therapists linked to the Sullivanian Institute for Psychoanalytic Research, a group established in Manhattan in 1957 that dissolved in 1991 with the death of its founder and supreme guru.

The story is told in a recently released book, “The Sullivanians,” by Alexander Stille, a journalism professor at Columbia University. Its founders – psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Jane Pearce and her colleague (and, at different times, lover, husband and adversary) Saul Newton – took the group’s name and its initial inspiration from the work of American psychoanalyst Harry Stack Sullivan, who died almost ten years before the Sullivan Institute opened its doors.

Mommy

Sullivan, a neo-Freudian, emphasised the psychological importance of adult friendships and peer relationships, in addition to the childhood relationship with parents, which was the focus of Freudian orthodoxy. As Stille succinctly put it, “Sullivan believed that personal growth comes from relationships with others, even in adulthood.” In Stille’s words, Pearce and Newton “took these ideas much further.”

They essentially argued that the family was a toxic structure, and that the worst thing that could happen to a child was to be raised by his or her biological mother: “Pearce and Newton believed that the nuclear family caused most psychological problems and that the mother inevitably crushed the vitality of her children.”

Read this way, in the journalist-historian’s objective text, the phrase “the mother inevitably crushes the vitality of her children” sounds like the tired old joke that, from the point of view of the psychoanalytic tradition, all problems always end up leaving a trail that leads back to the mother. But this is not exactly a cliché or a joke. It is much more a reduction to the absurd, what remains after the small talk and rhetorical flourishes are put in parentheses and, finally, we have a clear view of what is, in fact, being said, without beating around the bush.

Consider, for example, this excerpt from an overwhelmingly positive 1964 review of Pearce and Newton’s book, “The Conditions of Human Growth,” published in 1963:

…the self-system is shown here acting (…) in an attempt to prevent the eruption of the unbearable anxieties caused to the infant by the mother’s inevitable withdrawal and rejection of certain aspects of its vitality. Thus, from the very beginning, socialization becomes a form of unconscious and painful hypocrisy (…). The cliché of not throwing the baby out with the bathwater is not much fun for infants, especially if their mothers are sensitive to dirt or nudity.

Let us remember that none – absolutely none – of this has the slightest basis in evidence. As is often the case in the psychoanalytic tradition, what we have are armchair musings, supposed introspective insights based on concepts that derive from armchair musings and previous insights, sometimes illustrated by case histories, always of dubious credibility and cherry-picked.

Much of “The Sullivanians” is made up of testimonies from former members of the group, some traumatised survivors, others with more positive memories. All of them, however, point to Saul Newton’s inflated ego, the autocratic, cruel and misogynistic nature of his personality, his megalomania and paranoia. There is the moment when he starts demanding oral sex from patients during therapy sessions, declaring rape part of the therapy. There is the moment when he carries out a “coup d’état” that excludes Jane Pearce from the leadership of the Institute.

The collapse of the Sullivanian community began in the 1980s, after a young mother, unable to accept the separation from her baby imposed by the group’s doctrine, “kidnapped” her own daughter and then went to the press, seeking support from the people and the authorities.

Analytical culture

One issue that Stille only touches on in his book is the extent to which psychoanalytic culture facilitated, enabled, or fuelled the Sullivanian sect. That “psychoanalytic culture” is the milieu formed by artists, intellectuals, and professionals, united by reverence for the image (academic or popular) of what psychoanalysis is or should be, its aura of authority, and its inflated claims to validity. It stems from an atmosphere where what one breathes are the ideas and words of Sigmund Freud, as filtered by other intellectuals, thinkers, and popular culture; an environment in which these ideas, words, and their multiple versions become part of the everyday lexicon and are accepted as part of the common sense of educated society.

It is no coincidence that the Sullivanian experiment began at a time when psychoanalysis was at the height of its prestige,” the journalist writes. And further on: “In the mid-20th century, psychoanalysis reached the culmination of its prestige, popularity and authority, especially in the United States (…) Time magazine put Freud on the cover three times between 1924 and 1956.

Early on, in the 1950s, the Sullivans had their moment in cultural fashion: in 1955, Clement Greenberg, then New York’s most influential art critic, began seeing a disciple of Saul Newton and was enchanted.

At a time when it was – to paraphrase an art historian interviewed by Stille – almost impossible to be taken seriously in society, as an artist or intellectual, without having to sit on a couch, Greenberg’s seal of approval gave the Sullivans a chic, “hip” air, even before the institute was formalised. Jackson Pollock, facing a creative crisis, decided to seek treatment from a Sullivansian therapist, following what might be described as an emphatic suggestion from “Clem” Greenberg.

Describing the scene on the Upper West Side, a section of Manhattan favored by musicians, artists, and journalists in the 1950s, Stille writes:

The area was teeming with intellectuals and psychiatrists: a common joke was that if you threw something out a window on the Upper West Side, you were likely to hit a shrink.

At the right hand of the Father

Fanaticism, isolation, disconnection from reality, blind and abject obedience to the leader-guru – these are pathologies normally associated with religion, esotericism or political ideology. The idea of psychotherapy as the raw material of a fanatical sect seems difficult to process. But psychoanalysis has characteristics that make it vulnerable to this type of degeneration.

Psychologist Robert Jay Lifton, a scholar of “thought reform” systems – “brainwashing” would be a more melodramatic term – identifies two characteristics that are always found, together or separately, in the formation of sectarian movements. One is ideological totalism, defined as “an all-or-nothing set of ideas that claim to contain nothing less than absolute truth and virtue.” The other is the presence of an omniscient and infallible guru, or, as Lifton defines it, a “mental predator.”

It is very difficult to deny that psychoanalytic doctrine – both Freud’s original and its more popular dissenting theories – has totalist pretensions. For those who really take it seriously, psychoanalysis is the interpretative key that opens the doors not only to psychopathology, but to all human behaviour, to the political-economic situation and to the very essence of civilisation.

The predisposition of psychoanalysis to produce gurus venerated as omniscient, targets of idolatry, is also a historical fact, starting with Sigmund Freud himself. The stenographer in charge of taking notes on Jacques Lacan’s seminars, Maria Pierrakos, describes, in an autobiographical pamphlet (“Lacan’s ‘Scouter’”) and in terms worthy of a New Testament narrative, the atmosphere surrounding the French theorist’s speeches:

… the Master arrives, goes up on stage and begins to speak; a mystical silence sets in (…) would it be possible to miss a single word? (…) On stage, only a privileged few (…) I saw a very beloved disciple ascend to the right hand of the Father….

In a famous series of lectures given in 1975 (“Nostalgia for the Absolute”), one of the great intellectuals of the 20th century, George Steiner, placed Freud’s work on his list of “meta-religions” or “mythologies,” intellectual systems used to fill the emotional and social vacuum left by the loss of prestige of Christian dogmatism in the West.

Steiner lists the characteristics of these meta-religions: they are “totalising”; they have, in their conception, a “prophetic vision”, a narrative of origin with a genius-hero as protagonist; this genius-hero establishes a group of faithful disciples, from which some heretics break away; they are systems endowed with their own symbolic scheme, with jargon, emblems and metaphors that are specific to them.

“These great movements, these great gestures of the imagination, that have tried to replace religion in the West, and Christianity in particular, are very similar to the churches, the theology that they seek to replace,” he points out.

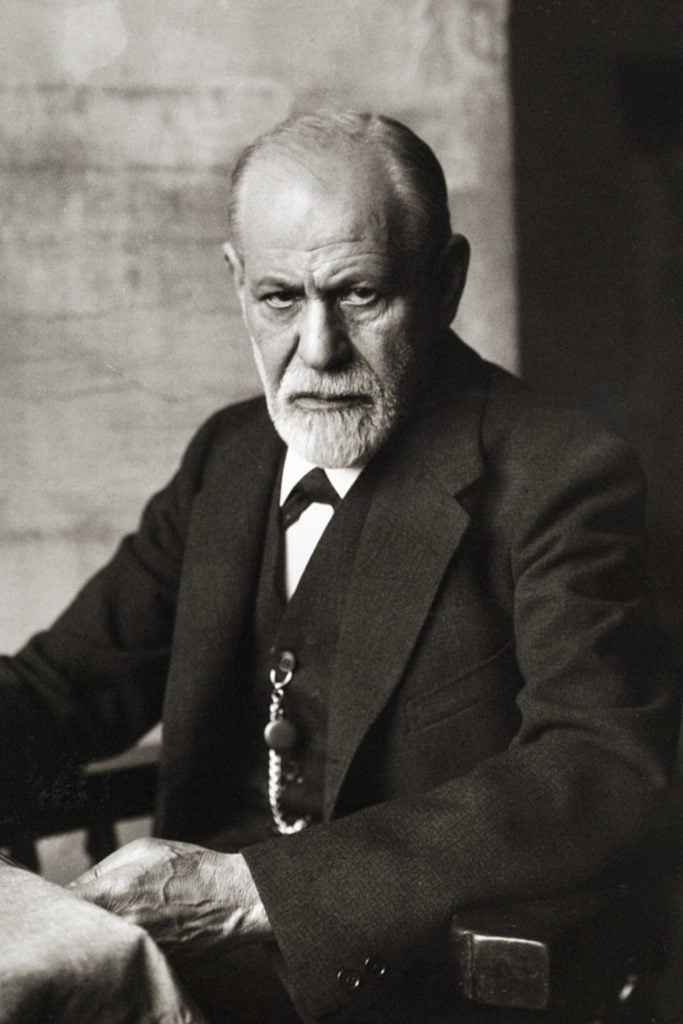

Steiner is not alone. The philosopher and anthropologist Ernest Gellner, in his book “The Psychoanalytic Movement”, also accuses psychoanalysis of being a religion in disguise: with irony, he says that the official history of the movement could very well be called “The Life and Passion of Saint Sigmund” (the house where Freud lived in London, converted into a museum, certainly resembles a shrine full of relics. The photo that illustrates this article is of the office, preserved today as it was in the 1930s).

It should not surprise us, therefore, that the similarity between psychoanalysis and religion, detected by Steiner, Gellner and so many others, includes the tendency, found in Christianity, Islam and the most varied creeds, to occasionally inspire fanaticism.

In any case, this is a curious risk for something that is presented as a therapeutic proposal. If psychotherapy came with a leaflet, it could be included on the list of possible adverse effects that should be carefully observed.