This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 2, Issue 6, from 1988.

When the Turin Shroud was last put on display in Turin Cathedral in 1978, more than 3.5 million pilgrims flocked to see it, but if it ever goes on public display again it will be merely as a 14th century work of art.

The results of carbon dating experiments carried out at laboratories in Oxford, Zurich and Arizona were, after a considerable delay, officially announced on 13 October and indicate clearly that the shroud is a piece of linen which was woven between AD 1260 and 1390. The image on the shroud of an apparently crucified man is now quite unambiguously not the image of Jesus Christ mysteriously imprinted at the moment of resurrection.

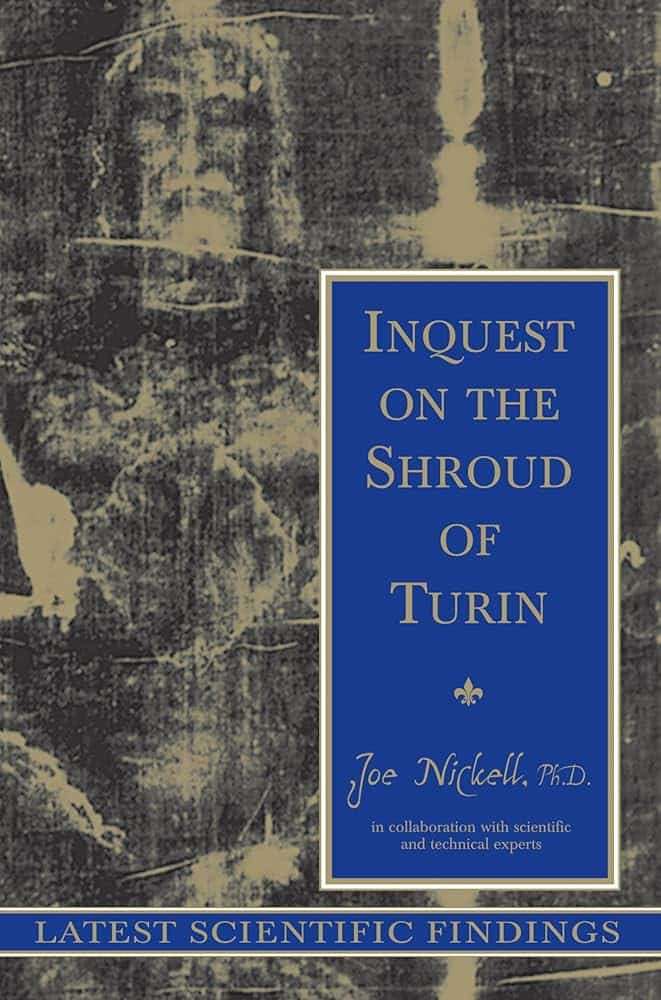

The only remaining mystery appears to be how a mediaeval forger managed to produce a lasting image which has some of the properties of a photographic negative. Dr Joe Nickell has spent a number of years researching this very question and has written a book on his findings entitled Inquest on the Shroud of Turin. On 29 September, two weeks before the long awaited official announcement, I interviewed Joe Nickell for the BBC Radio 4 programme, Science Now. What follows is an edited transcript of that interview.

SD: The aspect of the shroud which is in the news at the moment is the carbon dating, but what I’d like to talk about are the various hypotheses which have been put forward to explain the image. The reason for this is that, assuming that the question of the dating has been settled, I think the question in everybody’s mind is going to be how did the image get there, if it wasn’t by miraculous means at the time of Christ? Could you tell us a little about the various hypotheses that have been put up over the decades or over the centuries to account for the image?

JN: Of course. The shroud first came to light in the middle ages and the earliest report is a bishop’s report to Pope Clement that the forger had been found, and had confessed, and so the earliest claims are that the shroud image was cunningly painted. But, when the shroud was first photographed by Secondo Pia in 1898, it was found that the darks and lights on the negative were reversed. That is to say that when you looked at the glass plate negative you saw a positive rather than a negative image, and so the modern era of shroud studies really began there with people asking how it could be possible for a forger to produce a photographic negative in the middle ages.

Actually the question is a little bit of a bogus one because it isn’t a true photographic negative. There are blank spaces in the image that would not be in a photographic image. Also the colour of the hair is reversed, so that in a positive image Jesus looks like a white-haired and white-bearded old man.

But, putting that aside, the earliest obvious theory that would be consistent with the shroud being genuine was that it was simply an imprint made from the body being covered with the burial spices myrrh and aloes, and that this had caused an imprint on the shroud. The problem is, as I’ve found by experimenting along those lines, that you get a severe wraparound distortion. That is when you press a cloth around a three dimensional form like the human face with the nose sticking out the way it does, you get severe distortions with elongated eye sockets and other distortions that are really rather grotesque.

SD: So it’s a bit like a projection of the Earth’s surface onto a flat plane?

JN: It is a mapping type problem, yes, and it is such a severe problem there is no way of getting around it. Also people realised later that there were places which had been imprinted which would not have been touched by a draped cloth. So a fellow named Paul Vignon suggested that there must have been some form of imprinting across a distance. He postulated the so-called vaporograph theory, which included the notion that body vapours-weak ammonia vapours from morbid body sweat might have interacted with the burial spices on the cloth to produce a so-called vapour photo.

SD: But it seems to me that this would not give rise to a very detailed image.

JN: Right. In fact I experimented with that technology. I used a sculpture, coated it with ammonia and used a cloth treated with phenolphthalein and draped it over, and of course what I got is what most scientists could extrapolate would happen – a big blur. And that theory has been negated now and no one pays any attention to it.

Then, because of the faint brown or sepia colour of the image, which is approximately the colour of a scorch, people suggested that maybe it was caused by a burst of radiant energy at the moment of resurrection. The problem with that is that the image on the cloth is very superficial. It does not penetrate through the fibres to the back of the cloth. And while this was used to argue that it was not a painting, it also argues against radiation because there is no radiation known that would travel the varying distances from body to cloth and, as soon as it hit the cloth, drop to zero.

SD: So any kind of radiation, ultraviolet for instance, wouldn’t just scorch the very surface of the fibres. You’re saying it would penetrate?

JN: That’s right. But also there are problems with the fact that the image would really have to be focused in order to get an image that’s not blurred and distorted. What one is doing when one goes down that path is just invoking a miracle. And so the question then is whether there is any reason to invoke a miracle. Is the prima facie evidence of a nature that we should give up other explanations? And my position is that we know from a body of evidence that the shroud was produced by an artist in the middle ages.

SD: What scientific analysis, other than the carbon dating, has been carried out on the image and blood-stained areas?

JN: An earlier series of tests was done by a once-secret commission which later produced a report, although it has been very difficult for people to obtain copies of the original report. But we do know that they took threads out of the shroud from the so-called blood-stained areas and these went to forensic laboratories in which internationally known forensic experts tested them using all the standard tests, then the more specific tests for blood and blood compounds, and the fibres failed all those tests.

The Church authorities did not like this, apparently, so they issued a rebuttal report, but later the Shroud of Turin Research Project visited Turin and they lifted sticky tape samples from the fibres just by placing the tape on the cloth, peeling it off and mounting these on microscope slides. The samples were first analysed at the world-renowned McCrone forensic laboratories in Chicago. Immediately they found traces of various substances identifiable as paint pigments. They found red iron oxide of a type used in the pigment red ochre and smaller amounts of vermilion and rose madder.

SD: Are these all pigments that were used in medieval times?

JN: Right. Even some pro-shroud analysts found traces of the vermilion but much smaller traces than McCrone. One of the big questions was whether that red iron oxide was primarily on the image area or not. McCrone’s results, in a blind study, demonstrated that the iron oxide was on the image areas and very little on the off-image areas.

McCrone then took the view that the image was a painting. I have a problem with that viewpoint because again the body image is superficial and does not soak through the cloth whereas the so-called blood areas do soak through. Later tests after McCrone (although by pro-shroud people which makes a bit of a problem for objectivity) seem to have found that there is very little pigment or very little iron oxide, and that what you see as a body image is really just a yellowing of the cloth.

So what I think might have happened is that a powdered pigment was rubbed onto the fibres and over time that has caused a yellowing just by its presence on there. That is, by being slightly acidic, it has stained the cloth over time and most of the powder has been sloughed off.

SD: You have written a book entitled Inquest on the Shroud of Turin on your investigations into the shroud, and in the book you write about a type of rubbing technique which you have used to produce an image very similar to the shroud image. Can you tell me a bit about this and whether you feel that a medieval forger would have had the skill required to produce such an image?

JN: Joe Nickell master forger! Well, when I began to realise that wraparound distortion was a problem, and when I found out about the lack of history, the forger’s confession and so forth and also the presence of some reddish granules – although at that time we didn’t know what they were! – I began to seriously consider the possibility of artistry. I had eliminated contact imprinting. I had eliminated vaporography. The miraculous theory, of course, could not be tested and I felt was not yet warranted until we had tried everything.

So I then took the other category of possible solutions – artistry – and began to work on it. Immediately it occurred to me that a full three-dimensional sculpture would not work. But there did seem to be evidence that it was not a painting and that it did have three-dimensional information – there have been microdensitometer tracings and other studies that show that the darks and lights of the image are consistent with some kind of three dimensional form.

SD: Can we just recap on why you felt it wasn’t a painting? This was due to the lack of penetration of pigment into the fibres?

JN: Right. There was no evidence of capillary action where there would be a soaking of a fluid medium into the fibres of the shroud except in the blood areas. There also were no brush marks, and of course there was the phenomenon of light and dark reversal which would be another unusual characteristic for a painting.

And there were other indications. For example there were various flaws in the image that were interesting. There were the blank spaces we talked about earlier and a number of things that indicated to me that we might be dealing with some kind of imprinting technique from a bas-relief; a low sculpted relief, not a full three-dimensional relief, but not a flat plate like an engraving. So my first experiments were to try to make an actual print by coating the bas-relief and pressing cloth to it.

SD: So you’re talking about a fairly familiar technique – brass rubbing?

JN: Well that was the next step. Printing was a possible technique but it had some serious drawbacks. So I then tried a technique, as you pointed out, analogous to brass rubbing except that usually we put a paper on a fiat surface and rub it. In this case I was using cloth and a curved form, but by wetting the cloth and moulding it to the bas-relief I was able to form the cloth to the relief, rather like a mask.

Then, when the cloth was thoroughly dry, I took a dauber and some powdered pigment and rubbed it on carefully in strokes. When I did this the dauber hit the prominences and left the recesses blank, and since the prominences in a positive image, like a face, are in highlight my technique produced the prominences as dark areas. So it made a systematic quasi-negative image just like the shroud image. It had the darks and lights reversed, the hair was still white in the positive image, there were blank spaces and tonal gradations and, in all, there were some thirty points of similarity between my images and the shroud images at the visual or macroscopic level and even at the microscopic level.

The only differences, I believe, are those due to the effects of 600 years during which time the image would be expected to have yellowed the cloth and most of the powdered pigment would have sloughed off.

SD: How confident are you that you have arrived at the technique which was used in the 14th century to do the forgery?

JN: I have a very high degree of confidence. It is very unlikely, in my thinking, that the shroud is an ordinary painting. There are serious problems with that, although there are ways around the difficulties. For example if you wanted the pigment not to soak into the cloth you could give the cloth a coat of a sealer of some kind. The problem there is why would you have the blood areas soaking through; why would parts of it soak through and parts not? But it is also very difficult for a person to paint a negative image. It’s easy enough to copy one if you have one in front of you.

In other words, an artist can look at the shroud and copy it but, you see, he is sort of cheating because he has a negative already made for him to copy. It’s harder to take a positive image and translate it into a negative, whereas my technique does it automatically. And then I would point out that the technique I used duplicates a number of these very particular flaws and peculiar characteristics, and whilst those might be imitated by a counterfeiter, the question would arise why would you put these particular distortions, faults and flaws in? Whereas the answer for me for my technique is because that’s what my technique does. It just naturally produces them – blank spaces for example.

SD: So you’re saying for instance that when a negative photograph is taken of the shroud image and gives an apparently positive image the fact that the beard and hair come out white is a natural function of just the way it has been done?

JN: Yes, you see when we look at an ordinary photographic negative we’re looking at colours like brown hair which is dark because of its colour. But when we make a rubbing from a bas-relief, that which is raised will be dark, regardless. So the hair becomes dark on the original image but light on the apparently positive photographic negative, so there is that reversal of form. Now it may be that an artist, since rubbings were beginning to become common during the middle ages, had studied some rubbings and then did a painting imitating them.

I would point out too that there is evidence that the shroud image was once much darker than it is now. So it does appear that the image is losing pigment over time and so the problem is that when we try to figure out exactly what the artist did there is so little left of the original painting or printing that all we have is a residual stain and that does complicate it. Plus the fact that skeptical people with artistic training have really not been allowed access to it.

SD: Given the results of the carbon dating that seem to indicate clearly that the shroud dates back to the 14th century and not the 1st century, and given your findings on a fairly convincing method by which the shroud may have been forged, do you think this will kill forever speculation about the authenticity of the shroud?

JN: Well, it’s difficult to say. There may be some really pathological believers who simply can’t accept what everyone else will be able to accept.

But when you look at the totality of the evidence, and you look at the age of the cloth, which is now apparently established with a very high degree of accuracy as the same time as the forger’s confession, and you realise that this is supported by the lack of historical record, the method of wrapping the body which is contrary to Jewish burial practice, and the evidence from the paint pigment, the fact is that although we may disagree slightly about the method of artistic simulation, the skeptics have maybe too many techniques on their side whereas the believers have none. And so the evidence is just overwhelming and if all issues were this clear, life would be much simpler.

Joe Nickell’s book is published by Prometheus and contains photographs of ‘shroud-like’ images produced by the author using the technique discussed in the interview.

Header image: a replica Shroud displayed in a Polish church. Photo by Krzysztof D., Flickr