Negative feelings about “Big Pharma” have inundated our popular media. The pandemic and its associated medical misinformation, the controversies surrounding “Pharma Bro” Martin Shkreli and the Sackler Family’s Purdue Pharma bankruptcy have led people to believe that for Big Pharma to succeed, it requires people to remain sick.

With these stories and many others, it’s not hard to see why many people feel that “Big Pharma needs sick people to prosper,” and how this refrain could come to affect how people feel about pharmaceutical companies. While the pharmaceutical industry has done unethical and reprehensible things, as Dr Steven Novella writes over on Science-Based medicine:

“It has become fashionable, however, to not only criticize the pharmaceutical industry but to demonize them – and the term “big pharma” has come to represent this demonization. Cynicism is a cheap imitation of skepticism – it is the assumption of the worst, without careful thought or any hint of fairness.”

As a person that has worked in the pharmaceutical industry, I have felt that demonisation even in skeptical spaces. I have worked in the pharma industry for seven years, in positions from sourcing starting materials, sampling and analysing raw materials, and manufacturing and analysing intermediate products, active pharmaceutical ingredients, and finished products. I do not speak for any of the companies that I have worked for, and all views and opinions are solely my own.

While my experience does not cover senior management, sales or marketing, most of my post-college career has been in R&D and in the manufacturing and testing of drug products. Working in the industry, from raw material to finished products, has led me to have some insight into the “big pharma” conspiracy.

When I got my first job at a contract research organisation (CRO), which did specialty testing, our first day was focused on the history of the FDA in America and why it was created.

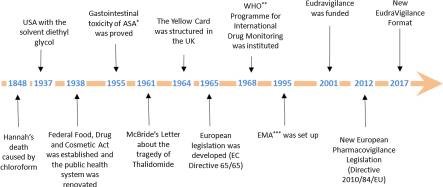

Throughout history, there have been many instances of drug adulteration and bad science that have led to deaths. The number one goal of those who manufacture and test pharmaceutical products is to prevent these incidents. As the world has learned from these tragedies, more tools and regulations have been created to not only catch similar incidents, but also to identify any new issues before a product goes to market. Many of the tools and systems that are put in place are used all the way through the process.

Working at the CRO, whose business was to specialise in analysing many different companies’ pharmaceutical and food raw materials all the way through to their finished products, informed me about many of the regulations and tools the industry uses to keep the end users safe from impurities and contamination. One of the most critical tools is current good manufacturing practice (cGMP) documentation. This takes scientific documentation to the next level, and is codified in the US and audited by the FDA.

As a brief overview, the principles of cGMP documentation are Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneously recorded, Original or true copy, and Accurate, plus complete, consistent, enduring and available (ALCOA+). In simpler terms: read a step, do a step, then document a step, and ensure that data is accessible. These regulations and document system together form a way of organising the manufacturing and testing process. This style of thinking highlights its purpose: everything a person or company does may influence the end user of the product. This might seem counterintuitive, but it is very effective for motivating staff to do the utmost, even on the longest days.

Another important set of tools, that go hand-in-hand with cGMP, are the pharmacopoeias. These include the United States Pharmacopeia-National Formulary (USP-NF), European Pharmacopoeia (EurP or EP), Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP), British Pharmacopoeia (BP), and Chinese Pharmacopoeia (ChP). These pharmacopoeias include monographs (a list of tests and specifications for a raw material, its active pharmaceutical ingredient or API, and/or inactive ingredients), general chapters (how to perform testing), and general notices (like presenting the basic assumptions, definitions, and default conditions for the interpretation and application of the pharmacopeia). While the pharmacopoeia outlines the minimum quality a material must have, many companies have extra quality checks and specifications. These additional specifications may help ensure that the purity of the final product exceeds the regulatory requirements.

At one point in my career, I was responsible for writing and revising raw material specifications. To create these specifications, I had to work with many people who were responsible for thinking about a unique aspect of the material. This team of people includes, but is not limited to toxicologists, material scientists, engineers, quality control scientists, and quality assurance. Not only did we have to consider the pharmacopoeias as they currently were, but it was our job to also think about what new regulations might come.

In addition to the chemicals that made up the product, we had to consider the reactors, tubing, and any other elements that could touch the process. When I would draft specifications, the documents would be reviewed by at least four people before a final Quality Assurance review, to ensure that all the information complied by each group was accurately documented and would meet or exceed the regulatory requirements. Most companies have this practice to ensure accuracy and accountability.

As time passed in my career, I saw the introduction of another key goal for pharmaceutical companies: creating a sustainable manufacturing and supply chain. This is not just a push from a regulatory body for more sustainable practices, but represents a culture change within the companies themselves. Some of that push is from the public, but most is from the younger generation in the pharmaceutical industry fighting for change. I have been part of the sourcing efforts and supplier grading to evaluate how sustainable a supplier’s manufacturing process is. From the outside, it may look like not much is being done, but more and more companies are starting to really challenge themselves and their supply chain to put such policies in place.

If we look at “big pharma” from a bottom-up approach, we can see that – while far from perfect – there are hardworking people wanting to make a difference in people’s lives. Like many things in the world, pharmaceutical companies must be weighed with nuance. Many of the tools and regulations discussed here continue to evolve through companies – and their employees – wanting to do better.

As we rightly scrutinise the pharma industry, we need to keep in mind that businesses are made up of people, and we need to have an empathetical eye, to avoid demonising everyone within an industry. Over the timeline of licensed and regulated pharmaceuticals, the average worker within the industry is genuinely trying to improve standards, ensure there’s less chance of accidental harm, and improve the safety of their products.