Being a skeptic is easy. All we must do is not accept a claim unless we see evidence for it. Then we must examine that evidence, but before that we don’t have to do anything. The point of skepticism is not to deny but to withhold assent. If someone tells me that I should get up in the morning and hand over 10% of my income, I don’t have to do that until I see some evidence for why. It’s a worldview that appeals to my laziness; I don’t have to do anything because the burden of proof is on the person making the claim.

Being a skeptic is easy — until it suddenly is not. Skepticism is hard when we have to defend concepts or people that we would normally despise. During the pandemic years I found myself defending the pharmaceutical companies — notably Pfizer, for whom I have a lecture on their practice of price inflation (Epanutin), and marketing of drugs for uses other than intended (notably Bextra). The practice was highly unethical and not unique to Pfizer; but I found myself saying and writing, “yeah, I know they did those things, but the vaccine seems to be effective and largely safe…”

Then several months ago, I found myself earning scorn from some and credit from others because I was defending the former Pope against people labelling him a Nazi. I tried to point out that the evidence is clear that all German boys were conscripted in the Hitler Youth at the age of 14, with the threat of criminal prosecution if they did not comply. So, yes, while he did wear the uniform, it’s more akin to being a child soldier than a willing participant, and there is a salient difference between being forced to do something and wanting to do it. Here I am, an avowed atheist and skeptic defending the individual singularly responsible for enforcing the crimen sollictationis — the document which guided the Vatican’s behaviour in hiding priests from legal consequence. His actual crime is reprehensible enough that it is unnecessary to have to make up another for him. In both cases I feel an ethical obligation to adhere to what seems to be the truth.

Evidence, we say, will move us. That mantra is the one thing that I brag about the most when people ask me what the advantage of skepticism is. Sure, we tend to care less about a person’s race, sexual orientation, gender identity, or any of the other things that have been historically used to devalue entire groups of people; that is the moral position, but it is the moral position because there is no evidence that any of those things makes an individual less of a person. It’s the suspension of assent without evidence that is, again, our greatest virtue.

Inevitably, this becomes very difficult when the evidence runs counter to something we want to be true. Which brings me to the topic of Medical Marijuana/Cannabis. I know plenty of cannabis enthusiasts who have assured me that the plant has medical benefits. Some of these people are even skeptics, so it should be an easy enough task to find the evidence that confirms the medical benefits of the marijuana plant. Unfortunately, the evidence is not as robust as the legends make it out to be.

There are two disclaimers I have to put forth: the first is that in the US and the UK; legal restrictions on the substance have made it difficult to even research it for medical reasons. In the UK this restriction was repealed in 2018, while in the US the problem varies between jurisdictions but as a drug, it remains a schedule 1 — the most serious of classifications, which renders research into it very legally odious to conduct.

The second is that I am not anti-marijuana. I personally don’t care for it, and as someone with a PhD in Philosophy I know that I’m in the minority of non-pot smokers in my discipline. My position is similar to Mill’s: do what you want, as long as everyone consents, and no one is being harmed.

The concept of medical marijuana seemed to be nothing more than a gateway argument. It was a way to open the door to full legalisation. I thought it was similar to the way that people, during the American experiment with alcohol prohibition, could get medical whiskey prescriptions (including a certain UK Prime Minister). Yet smokers assured me that it had benefits that were as good, if not better, than their pharmaceutical counterparts. Given the fervour by which they advocate for its effectiveness, it felt like the evidence must exist.

Glaucoma

There are two frequent claims I have heard advocating medical ganja, and the first is that it helps with Glaucoma. Glaucoma is a condition affecting the eye that can result in total blindness. There are a number of factors that cause glaucoma, and a few different kinds of glaucoma as well. Whatever vision loss an individual receives from the condition is considered permanent.

The most common factor in developing the condition is internal eye pressure, with family history being a close second. Though I should communicate that family history means an elevated eye pressure which causes the glaucoma. There is no known cure for the condition, but there is treatment to stem its development. But why would anyone think that smoking the reefer would help with glaucoma?

In 1980 a study, “Effect of Marihuana on Intraocular and Blood Pressure in Glaucoma,” (Merrit et al 1980) found that after use the internal pressure of the eye decreased enough to provide relief. In 1978 Green et. al found the same thing in rabbits using a topical oil treatment. This was an important finding, because the treatments for glaucoma at the time had deleterious side effects. Lighting up a spliff seemed to be effective and with fewer and less severe side effects. So, the evidence supports the claim, right?

Well, no. The first problem is that there is a difference in the concentration of THC. According to Pujari and Jempel (Pujari and Jempel 2019), the Merrit study used a concentration of 2%, while concentrations today greatly exceed that, and we should all understand that dosage matters. Secondly, it must be understood that the undesirable side effects for glaucoma medication were present in the 1970s. Medical science has developed treatments that have mitigated those side effects and are more effective at treating the condition. Most importantly though, the treatment works temporarily – very temporarily. According to Sun et al, to keep the condition under control would require frequent use though out the day; and while that may appeal to some people, the point here is to be treating a condition not spending the entire day blazed.

Cancer

The second most common claim about smoking endo was that it helped with cancer. This would mean that we could place this substance next to literally every other alternative medicine. The trouble with calling something a “cancer cure” is that the term is basically a red flag for a CAM treatment. Can the devil’s lettuce cure cancer?

The main problem with this claim is that there are a lot of different cancers. “Cancer” is more of an umbrella term than a specific disease, so the claim that one substance can cure all cancer is a bit farfetched to begin with. I’m not going to run through each of the different type of cancers and whether smoking a blunt will help treat it; so, I’ll make a general claim that there does not appear to be evidence that bud is going to help treat cancer. One study showed some promising signs that THC combined with Temozolomide (the standard chemo-therapy agent) could help stem the growth of a particular form of glioma (Torres et al 2011). The important thing about this study is that the combination of THC with the Temozolomide was not the animal subject getting baked and then undergoing chemotherapy, it was purified THC administered to target glioma cells that were chemo-resistant.

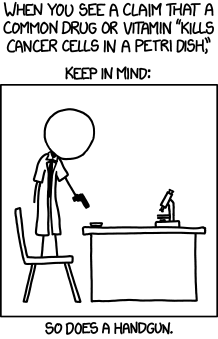

In breast cancer the effect seems to be null. In pre-clinical settings there was evidence that THC worked to inhibit some of the growth of oestrogen receptor positive breast cancer cell lines (Dobovisek et al 2020). However, this claim was based on a pre-clinical overview of research, which was theorising on the interaction between cannabinoids and sex hormones. While this does show the possibility of effectiveness, more research is certainly needed. Many things can stop cancer cells in a lab, not all of which translate well to actual human patients, and the authors warn about the interaction between THC and established treatment regimens.

Another claim is that dagga helps fight lung cancer. Despite what enthusiasts want to claim, smoking anything is bad for you. Inhaling smoke should not be considered “healthy.” While inhaling some burning substances may be healthier than others, this is in relative terms and not in absolute terms. Aldington et al (2008), showed an 5% increase in lung cancers in young adults who are habitual users of the wacky backy. Given that habitual use actually increases the risk of lung cancer, it’s contradictory to assume that it would help.

As a cancer treatment it looks like there is no sufficient evidence to make the claim. However, as some of the more zealous advocates are probably screaming at their screen, it doesn’t help treat cancer, what it does is help treat side effects of chemotherapy.

To be as brief and glib as possible: chemotherapy is a carpet bomb tactic. The treatment attacks everything with the understanding that cells which normally belong to the body will begin reproducing and the “flukes” will have been eradicated. As a treatment it is devastating to the human body. The side effects of chemotherapy include all manner of digestive complications: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, and constipation. These conditions may create an unwillingness to eat in the patient. There is evidence that suggests medical marihuana will alleviate these problems while improving the quality of life of patients undergoing treatment (Worster et al 2022). Unlike those people who claim that diet helps treat cancer, refusing to eat is not going to help the patient get better. One side effect of getting ripped is that the user gets “the munchies” – the irresistible craving for Funyuns, takeaway tacos, and sliders. It’s not a direct medical benefit, but it does help the patient overcome the unwillingness to eat.

Pain

That herb treats pain seems obvious. However, we should be clear on what we mean by a “treatment.” Are we asking whether a substance addresses the cause of a condition which is causing chronic pain or are we asking if the intervention covers up the sensation of pain with a different feeling? Cannabis-based pain therapies have so far only been suggested to do the latter. In this manner they function no differently than alcohol—if I’m drunk, I don’t feel the pain; likewise, if I’m blitzed, I do not perceive the pain.

A meta-study released in 2022 by Gedin et. al argues that cannabinoid success in treating pain is not objectively verifiable. They concluded from an overview of 20 studies involving 1,459 individuals that what seems to be the mechanism of action is our good friend the placebo effect. The presence of the placebo effect is easy to explain here – reported pain can be modified by the expectation of a positive result due to the favourable press coverage of a once illegal drug, as the authors write, “The unusually high media attention surrounding cannabinoid trials, with positive reports irrespective of scientific results, may uphold high expectations and shape placebo response in future trials.”

To conclude, more research is certainly needed. The restrictions on running studies on the substance are being slowly chipped away and its placement as a schedule 1 drug in the US is an absurdity. However, as Science Based Medicine has written, the current state of the science does not provide the conclusions that advocates have claimed.