During the Second World War, the Nazis gave their soldiers meth, aka the drug methamphetamine. No one is disputing that. What is however worth disputing is the delivery mechanism of that meth – specifically, the existence of so-called “Panzerschokolade”. According to legend, the Nazis mixed meth with chocolate to create “tanker’s chocolate”. The only problem is, there is no evidence to suggest that this tanker’s chocolate ever existed.

Amphetamine was first made in Germany in 1887 by the Romanian chemist Lazăr Edeleanu and methamphetamine (meth) was first synthesised a few years later in 1893 by Japanese chemist Nagai Nagayoshi. By 1938, the pharmacology of meth was fairly well understood, and it was sold and marketed as a non-prescription drug in Germany under the brand name Pervitin. It was known to heighten alertness, increase risk taking and suppress the appetite.

The Nazis gave their soldiers Pervitin in the opening phases of the war. The drug helped the soldiers stay awake during battle, effectively curing sleep. However, they soon noticed side effects: after the period of alertness came a crash, with the soldiers becoming confused and irritable. Therefore, by 1940, the Wehrmacht cut back on using Pervitin, limiting its consumption to a few pills at a time.

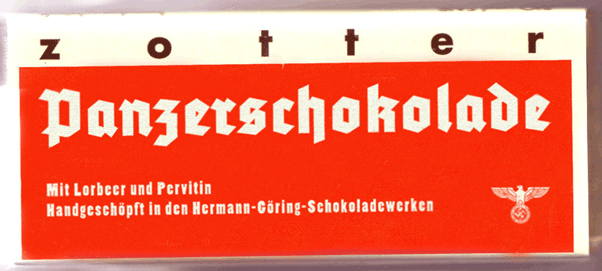

The huge consumption of Pervitin by the Nazis gave us the idea that they put it in everything, including chocolate. With the advent of the Internet, the following image did the rounds:

The image shows a wrapper for Panzerschokolade, made by the confectionary company Zotter. However, it is a fake. We know that it’s fake for several reasons. Firstly, the text roughly translates as “Panzer chocolate: with laurel and Pervitin. Handmade in the Hermann Göring Chocolate Factory”. It won’t surprise you to learn that the Hermann Göring Chocolate Factory never existed (Hermann Göring’s name was used for an industrial complex during the second world war, but that’s another story).

But the real kicker as to why this image is fake is that it’s attributed to the company Zotter. The company wasn’t founded until 1987, more than 40 years after the war ended. Zotter didn’t even open its first factory until 1999. The prevalence of the image caused Zotter to put out a statement where they denied any connection to so-called “Panzerschokolade”:

A fake image of a supposed “Panzerschokolade“(tank chocolate) in combination with our trademarked Zotter lettering has been circulating on the Internet for many years now, resembling a Zotter hand-scooped chocolate. According to the image, the chocolate should contain laurel and pervitin, a drug containing methamphetamine, which was handed out to soldiers during the Second World War to make them more efficient – ‘handmade in the Hermann Göring chocolate factory’. However, this Panzerschokolade never existed.

So, the “Zotter” Panzerschokolade is fake, but what about other brands? Another potential candidate is Scho-Ka-Kola. This German dark chocolate was first manufactured in 1936, and it was sold in round canisters. It was rationed to Wehrmacht soldiers in the second world war, and it was known as “Flyer’s Chocolate”. Yes, Scho-Ka-Kola was considered a pick-me-up, but it did not contain methamphetamine. The stimulant found in Scho-Ka-Kola is caffeine, provided by coffee and kola nuts. In fact, Scho-Ka-Kola is still made and sold today, having barely changed since the second world war.

As of yet, there is no good evidence for the existence of “Panzerschokolade”. But what would be considered good evidence? When historians talk about sources, there are two kinds: primary and secondary. Primary sources from the second world war would include photos, packaging and first hand accounts such as letters. Secondary sources are articles about primary sources, such as books and journal articles. They should make reference to the primary sources they refer to.

So, where is the primary evidence of Panzerschokolade? As far as I can tell, there isn’t any. Are there any photos of Nazi tank crews passing around a bar and chowing down? No. Do any museums have a tattered wrapper on display as a fascinating curio? Nope. What about a diary entry from a Wehrmacht soldier where he details perking up after munching on some meth-laden confectionary? Not to my knowledge.

Is there secondary evidence for the existence of Panzerschokolade? Yes there is. In his book “Shooting Up: A History of Drugs in Warfare”, Łukasz Kamieński, an associate professor at Krakow’s Jagiellonian University writes:

Methamphetamine was dispersed in the form of chocolate bars too – as Fliegerschokolade (flyer’s chocolate) for pilots and as Panzerschokolade (tanker’s chocolate) for panzer crews.

Does this mean that Panzerschokolade existed? Well, no. This statement is not referenced. Without references, this statement is not evidence in itself for the existence of Panzerschokolade. It could be a throwaway line put into the work based on a rumour the author heard. Maybe it’s something heard on the grapevine that’s become an accepted narrative without anyone checking it?

We cannot say with 100% certainty that Panzerschokolade never existed. After all, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. However, until primary evidence of Panzerschokolade comes to light, our working hypothesis has to be that it never existed.