On Sunday 14th November, Liverpool was the scene of a terrorist attack. Just before 11am, a taxi pulled up to Liverpool Women’s Hospital, and just as the car stopped, an explosive device went off inside of it. The event was captured on video, and you can clearly see the moment the bomb goes off, the windscreen blows out, the car starts emitting white smoke, before the smoke turns black and the vehicle is soon engulfed in flames.

There was only one person killed in the explosion – the bomber himself, a 32 year old called Emad al-Swealmeen, who was born in Iraq and arrived in the UK in 2014, claiming asylum as a Syrian refugee. Al-Swealmeen had seen his asylum application turned down in 2014, and his appeal was rejected in 2015. Whether the Home Office made any efforts to remove him from the UK since that appeal was rejected is unclear – the department has refused to provide any information to the media on how it handled the case.

One other person was hurt was the taxi driver David Perry, who managed to get out of the car shortly before it burned. David suffered some injuries and required some surgery to his ear, but was discharged the next day and is recovering.

By all accounts, the incident could have been a lot worse – it’s not clear if the bomb was designed to go off when it did, or whether it detonated prematurely, possibly as a result of the car coming to a stop. It was described by Assistant Chief Constable Russ Jackson as having the potential to have caused significant injury and death. The timing of the explosion raised a lot of alarms, too, as it was at 11am on Remembrance Sunday, just before the country fell into a customary two minute silence in order to remember those who lost their lives in war.

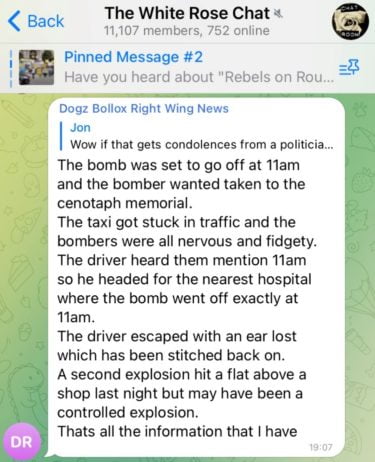

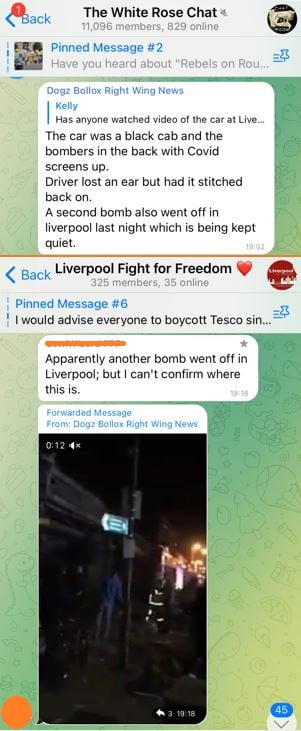

Within minutes of the bomb going off, the speculation began – as did the proliferation of misinformation. There was the speculation that al-Swealmeen’s real target was the Cenotaph, given that it was Remembrance Sunday. I saw this rumour spreading both on Twitter and also via Telegram, where the conspiracy theory channels I monitor were taking a keen interest. Except, this clearly couldn’t have been the case, because Liverpool’s remembrance event wasn’t taking place at the Cenotaph – it was taking place at the Anglican Cathedral, on Hope Street. The people who were confidently spreading the information they’d received from their sources hadn’t even bothered to check if there was a public event on at the Cenotaph.

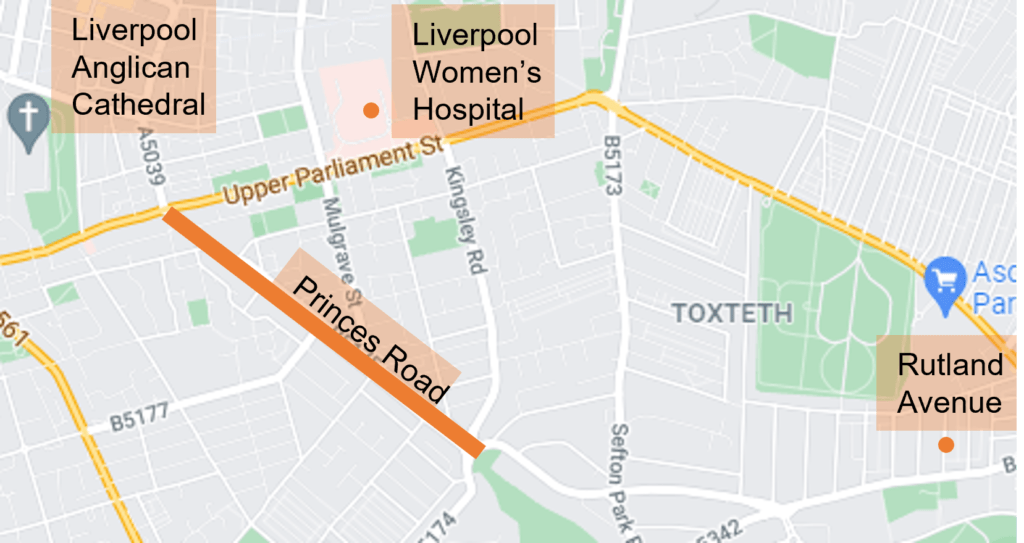

Soon, those in the know switched their facts, to assert that their sources told them the bomber had been targeting the cathedral after all, but was foiled by unexpectedly heavy traffic. Again, this made little sense: he started at Rutland Avenue – from there, most routes to the cathedral (such as Princes Road – effectively a dual carriageway) were not busy at that time on a Sunday morning.

If he was indeed foiled by the traffic, why would he have pulled into the car park of the Women’s Hospital, on Crown Street? There were those confidently asserting that he simply got dropped off at the Women’s Hospital in order to walk to the cathedral – again, a completely nonsensical idea to anyone remotely familiar with the area or the hospital car park.

In one Telegram channel, a local conspiracy theorist explained that al-Swealmeen had asked to go to the cathedral, but the taxi driver saw him acting suspiciously and so decided not to take him to his destination, but to head for the nearest hospital instead, just in case. One might wonder why a nervous taxi driver would choose to drive to the hospital with the specialist neonatal clinic. “If you’re sitting next to a bomb set to go off in 5 minutes you don’t choose what hospital you drive to”, came the reply. Again, the story didn’t add up: how would the driver have known he had five minutes left to act? During a journey that would normally take less than 10 minutes? And if it were the case, would the driver detour to a place that was densely packed with sick people and newborn babies, rather than find somewhere less populated?

When it was subsequently confirmed that al-Swealmeen had asked the taxi driver to take him to the hospital, those who were so confident that the cathedral – or was it the Cenotaph? – was the target once again quietly adjusted what their official sources had been telling them all along.

That the hospital was the intended target made sense to some speculators on social media, including some who would consider themselves critical thinkers, as they sagely opined that the bomber was an anti-vaxxer stepping up the campaign of violence and intimidation against hospital workers. Or, given the specialism of the hospital, it was definitely an anti-abortion advocate who was there to take away women’s reproductive rights. None of this was based on anything other than speculation, none of it any better than that from outright conspiracy theorists, yet it was shared with confidence, adding to the confusion and misinformation as events were still unfolding.

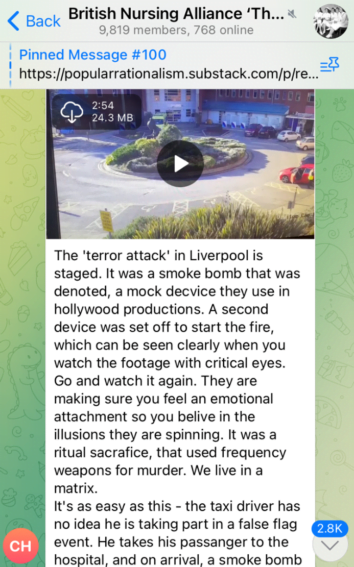

Soon, footage of the explosion emerged, inevitably instantly becoming the subject of intense scrutiny by those looking to reveal the ‘truth’. Several Telegram channels shared a viral frame by frame analysis of the explosion, with a knowing voiceover explaining that it just didn’t seem right. According to the analysis, the white smoke pouring out of the car was nothing but a smoke bomb. The narrator worried less about explaining what made the windows blow out and the windscreen fly high into the sky.

As the driver exited the vehicle, and as several other passers-by move away, the smoke began to turn darker – the narrator explains that there is “still no fire in the car”. The video zooms in to show a man dressed in black come out of the hospital and begin walking around the car. “What’s he doing now?” asks the narrator, “Oh, what’s that? Did that just set on fire, or did he set it on fire?”.

Despite the viral conspiratorial musings of our narrator, this is weak evidence of a false flag event. For one, his narration is a poor fit for what we see in the video – such as the explosive force great enough to send the car’s windscreen high into the air, or the smoke turning from white to black (a likely indication that the small fire has spread and is beginning to burn some of the inner materials of the car). Just because flames aren’t visible throughout the video, doesn’t mean the car wasn’t on fire throughout.

Equally, for this conspiracist hot-take to hold any merit, it would help to understand what the point of this extra step would be. Once ‘They’ (whoever They may be) had set up al-Swealmeen and a smoke bomb, what would be the benefit of an extra step which involved another device and co-conspirator? Why blow the car’s windows and fill it with smoke, only to then have another man have to come along to set it on fire? Why is that a better explanation of what we saw – what could that subterfuge possibly accomplish?

Once the excitement of the bomb had begun to lose interest for conspiracy theorists, they turned to the ongoing police investigation. One Telegram user shared a video of the aftermath of a second bomb, which the authorities were keeping quiet. This second bomb, apparently, had exploded in a flat above a shop ‘somewhere in Liverpool’. Where in Liverpool? No idea, just somewhere, but the police are covering it up.

Despite the cover up, however, there was a video of the aftermath of the explosion, which was quickly spread around dozens of channels. In the video, twenty or more people can be seen standing in the dark around a large cordoned-off space as police officers and firefighters survey the smashed glass and widespread debris. If the police were truly covering up any information about this supposed second explosion, they clearly weren’t doing a very good job, given how widely the video was circulating. Perhaps their cover-up efforts were too focused on somehow making sure that none of the dozens of people seen in the video would mention to anyone what they saw, nor take any footage (besides the footage we were obviously watching). Presumably, the police would have had to work hard to ensure nobody reported any of the dozens of alarms that could be heard loudly going off throughout the whole video, alerting anyone who somehow missed the explosion. The police would clearly have their work cut out.

Except, of course, they wouldn’t, because this was not a second explosion related to the bombing of the Women’s Hospital – this video was actually footage of a 2017 gas explosion that brought down a building in Bebington, on the Wirral. It had nothing at all to do with the bomb.

This kind of speculation in the wake of a terrorist attack is, of course, nothing new – we’ve seen it countless times before, from the intense scrutiny that emerged following the September 11 attacks, to the dangerous online ‘witch hunt’ that accompanied the Boston Marathon bombing. However, this kind of speculation only serves to provide an environment where misinformation and rumour thrive – causing further confusion.