While writing a previous column, I was informed that ‘culture war’ is perhaps not as widespread a term as I had thought. I was surprised, since the term is ubiquitous on this side of the pond and there is no end of culture war discussion in American political media. Yet it appears the term is only just now oozing into non-American zeitgeists, as various media interests seek to globalise current hot button American culture war issues like trans rights and “woke” critiques of historic figures. Many of you may have avoided these discussions, assuming they’re another toxic American export, akin to cultural high fructose corn syrup. I can’t blame you; we’re not sending our best. Sadly, as skeptics, the culture war is something we can’t ignore. As I discussed in my first article, skepticism is fundamentally tied to social justice, which makes us combatants in the culture war whether we like it or not.

Battle reports from the culture war are often deeply contradictory, and not always for purely partisan reasons. Some have declared that the culture war is over and conservatives lost, while others declare it will rage out of control forever. Some consider the culture war a crucial battlefront for social change, while others argue it’s a distraction that sidelines genuine change. Some argue that culture wars are a universal phenomenon, while others see it as a distinctly American pastime. Some argue that the current culture war is fundamentally distinct from prior incarnations, while others argue it’s an understandable evolution of the same debates about justice going back hundreds or thousands of years.

Debates over these narratives are themselves a part of the meta level of the culture war, the level at which individuals try to shape how we understand the discourse itself. These meta level debates about narratives seem to be increasing in our very online internet world. I’m going to explain how I understand the culture war, and though my explanation is undoubtedly tied up with my own narratives that I inherited from my progressive leftist upbringing, I hope it will shed some light on this complex phenomenon for those not raised within it.

I believe the culture war is ongoing, that it is unlikely to end any time soon, and that it’s likely to get worse before it gets better. While it can be used as a distraction, I believe the culture war is a crucial front for social change, because it is fundamentally a conflict between competing ways of understanding the world, and the implications go far beyond the toppling of a few statues. While culture wars exist across the world, I worry that America remains in the grip of a particularly virulent conflict, one that stretches back through much of American history. To motivate this view, let me provide a much-abridged history of America’s culture war.

Social Justice vs Traditional Values

Out of the many attempts to define the culture war, I’m most sympathetic to Russell Johnson’s account of it as a conflict between competing worldviews, which Johnson labels “social justice” and “traditional values”. Understood this way, the culture war traces its roots at least as far back as the American Civil War, which centered on the traditional value of conserving slavery.

As a debate between progressive “social justice” values and “traditional” conservative values, the culture war transcends discrete topics like gay marriage, and so maintains prominence in a world of rapidly passing topic fads. The other advantage of this definition is that it avoids the misconception that the culture war is only about “social” issues like gay marriage, and so is separate from economic conflict. The resistance to racial equality in the US has always walked hand in hand with overwhelming fear of economic equality, exemplified in the resistance to reconstruction, the persistence of Jim Crow policies, and the anti-communist paranoia that has driven much of right wing politics in America from World War One onward. Indeed, during periods like McCarthyism, one could argue the culture war centered on economic fronts, and issues like homosexuality were involved more insofar as they were associated with communism. The key point is that “traditional values” can mean being pro-life or it can mean the freedom to be as exploitatively capitalist as the law will allow.

While the roots of the culture war go back as far as slavery and colonialism, the historical accounts of America’s culture war that I find most valuable emphasise the rapid social change of the 60’s and 70’s as the jumping-off point for the current round of open conflict. Slavery and segregation made America a powder keg of racial animus, and the greater autonomy women achieved during wartime raised serious doubts about the relegation of women to the domestic sphere. These tensions came together to produce the period of violent cultural upheaval that we now call the civil rights era.

Despite modern universal love for figures like Martin Luther King Jr, the civil rights movement was not well received at the time by the white majority, even in northern states. It wasn’t until JFK’s assassination that Lyndon B. Johnson had sufficient political power to pass the 1964 Civil Rights Act, a major piece of legislation that outlawed discrimination based on a variety of features, including race and sex. There is a story, possibly apocryphal, that Johnson’s comment on signing the law was “we have lost the South for a generation”. Whether he said it or not, the comment turns out to be an understatement, as Democrats have never recovered in large swaths of the deep south, with the recent and notable exceptions of Virginia and Georgia, two states with large minority populations.

The Southern Strategy

Johnson couldn’t have imagined how much the GOP (another term for the Republican Party) would go all in on the “Southern strategy” – the explicit plan by post civil rights Republicans to hold power by focusing their energy on playing to white fear and anger over desegregation and other forms of social progress. GOP strategists believed they could control a large enough share of the white majority so that they wouldn’t need to court minority voters. As Kevin Philips, one of Nixon’s political strategists, put it (Content Note: racial slurs that are central to the point being made):

From now on, the Republicans are never going to get more than 10 to 20 percent of the Negro vote and they don’t need any more than that… but Republicans would be shortsighted if they weakened enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. The more Negroes who register as Democrats in the South, the sooner the Negrophobe whites will quit the Democrats and become Republicans. That’s where the votes are. Without that prodding from the blacks, the whites will backslide into their old comfortable arrangement with the local Democrats.

Despite the existence of quotes like this, and the clearly traceable shift of racist whites from Southern Democrats to the GOP, many on the right in America will still deny the Southern strategy was even a thing, or that the current demographic splits between the left and right in America are in any way the result of deliberate acts on the part of Republicans. I don’t know how anyone can hold such a position when you read this quote by another Republican strategist, Lee Atwater (Content Warning: even more racial slurs):

Y’all don’t quote me on this. You start out in 1954 by saying, “N****r, n****r, n****r”. By 1968 you can’t say “n****r”—that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states’ rights and all that stuff. You’re getting so abstract now [that] you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I’m not saying that. But I’m saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me—because obviously sitting around saying, “We want to cut this”, is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than “N****r, n****r”. So, any way you look at it, race is coming on the back-burner.

Atwater claimed that Ronald Reagan, who he advised, had no need to continue the Southern strategy. However, I would argue Reagan’s use of “welfare queens” and his aggressive war on drugs were both a straightforward continuation of the euphemism model that Atwater laid out. What’s more, Reagan’s smashing of unions continued the conservative war against anything that remotely resisted rampant capitalism.

As I mentioned, the Southern strategy wasn’t purely racial in nature. There was a corresponding backlash to the sexual revolution lead by conservative women like Phylis Schlafly that successfully resisted the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. Schlafly and others like Jerry Falwell aimed to reinforce an in-group mentality amongst white Christians by fearmongering about abortions, ‘pinko’ atheists, and feminists coming to destroy the institution of family.

On every front, the GOP aligned against social justice and progress, treating it as an existential threat to “traditional American values”. During this period there were constant right wing attacks on media and academia as hotbeds of communist unrest, which provided one major contribution to our post-truth world. In essence, everything we hear about on a daily basis now is one continuous cultural conflict more than 60 years in the offing.

Identity politics

As Ezra Klein has pointed out, it was also during this period that personal identities started to stack up in a unified way that made a critique of any one part of a person’s identity a threat to every part of their identity. There are a range of theories for why this happened, and I’m most sympathetic to the ones that focus on a combination of new technology granting greater media access and America’s dreadful winner-take-all political system that was built on a bunch of terrible compromises made with slavers to preserve the union. These factors produce the two massive and unwieldy political parties we know today.

The Democrats claimed the mantle of social justice, while frequently pushing neoliberal compromises, while the Republicans continue to actively resist social justice and the use of government to improve people’s lives, for fear of government overreach. Reagan in particular was successful at bringing together a mix of economic libertarians and fundamentalist Christians with an agreement that the libertarians would be free to focus on de-regulation of the economy while the fundamentalist Christians would be free to war against abortion, sexual liberation, and all the other heretical parts of the modern age. The unifying theme was Reagan’s famous quote, which is still central to the GOP ethos today:

Government is not the solution to our problems; government is the problem.

From the 80s to the 00s, a great deal of conservative political energy was focused on resistance to “the homosexual agenda”. It seems the GOP has lost so decisively on this issue that many seem to have suppressed any memory of Republican efforts to deny gay people basic human rights. Yet, as recently as 2004, Bush strategist Karl Rove was able to weaponise anti-gay marriage ballot measures to get Bush re-elected, a move that subsequent GOP strategists repeated in the 2010s with trans bathroom bills. The same playbook is still in use today, the target has simply shifted from gay people to trans people. One could also argue that the “war on terror” was a key part of the culture war. Muslims have not fared as well in terms of a sudden turnaround in acceptance, but the focus on them has waned, at least in America, as the battle over “wokeness” has gained ascendancy.

Culture war radicaliation hit another major speed boost with the election of Barak “did you know his middle name is Hussein?” Obama. This should have come as no surprise, but the intensity of the blowback was still unnerving. It wasn’t necessary for racism to be conscious in the minds of every GOP individual, though it was clearly conscious for many. Racial anxiety seems to work on a variety of levels. Research suggests our minds can mask it as economic anxiety, thereby generating a victimhood permission structure that justifies the anxiety. The key evidence that Obama’s response produced a unique reaction, besides the historic resistance by the GOP towards policies they previously supported, is the substantial uptick in membership amongst the sorts of radical organiations we saw storming the Capitol Building on January 6th. These militias feared that Democrats would use governmental tyranny to force a victory in the culture war, seizing guns and destroying traditional values once and for all. That fear was weirdly intensified by a president of colour, who presented an unavoidable visual reminder of a changing world.

Enter, Donald Trump

It was this energy that Trump harnessed, first with Birtherism and then with “Make America Great Again”, a phrase that exemplifies the traditional values side of the culture war divide. Trump knew how to activate culture war fragility in his followers, using it to isolate them and then using that isolation to heighten their anxiety further. Trump took the fertile ground the GOP had cultivated for 60 years and easily turned it into a cult of personality, with himself as the champion of traditional values, despite having lived a life that exemplified the opposite. There was a debate during the 2016 election over how many of Trump’s followers took him “seriously but not literally”. I think the storming of the Capitol makes it clear that, for many MAGA supporters, it was both.

Hopefully all this makes clear why my outlook on culture war armistice remains grim. Despite being out of office, Trump is still the leader of the GOP. The recent removal of Liz Cheney from GOP leadership merely for criticising Trump’s persistent and dangerous promotion of a “big lie” around his election loss proves that the GOP has no intention of bucking its current spiral. Meanwhile, racial animus itself isn’t going away, and there are a cadre of well-poisoners out there making sure any discussion on the subject is doomed from the start.

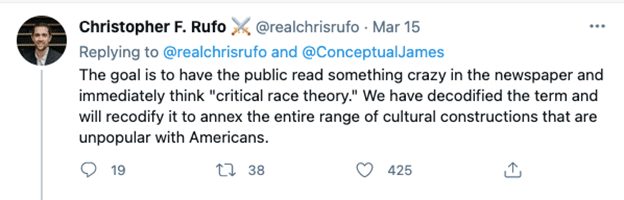

Take, for example, Chris Rufo, who I previously highlighted enjoying white nationalist memes with his face on them. Rufo is a conservative pundit who has continued the Southern strategy tradition of using euphemisms with his attack on Critical Race Theory, a view he admits he has willfully misrepresented to create a racially charged boogieman that doesn’t get the same blowback as overt racism:

Genuine social progress

If the culture war has been this constant tool of GOP politics, does that mean it really is a distraction from genuine progress? I don’t think so, because the culture war has also been a site of genuine success for progressive elements, and not just to get political power but also to enact some amount of social justice. It’s hard to imagine that the shift in opinion towards gay rights would have happened so quickly, relatively speaking, without concerted efforts by gay rights activists to fight the culture war on as many fronts as possible, from media representation to the mainstreaming of HIV/AIDS as an issue that extends beyond the gay community, to the centering of violence against LGBTQ youths like Matthew Shepard. Similarly, there is some hope that continued mainstreaming of democratic socialist ideas provides a path for addressing wealth inequality, a major exacerbating factor in the current culture war.

I wish I had more positive things to say about the right’s role in the American Culture War, but the traditional values they’ve chosen to defend seem deeply immoral to me. The most I can say in favor of the conservative position is that human society is changing very rapidly. Change can bring conflict and the risk that some valuable knowledge may be lost along the way. I do hope that conservatives can find a way to promote traditional values that really have retained their importance, such as community, and resist the urge to tie those values to things better left in the past, like regressive gender roles and sexual norms.

In future articles, I will look more closely at individuals and organisations involved in globalising the culture wars, as well as the focus on education as a key battlefield. For now, let me just say that the fight is worth fighting, and while we may sometimes be skeptical that progress is possible, it’s worth persevering, because you really can’t know which way things will break next.