Yesterday, news broke of a new clinical trial targeted at people who were overdue their cervical screening for cervical cancer.

The trial itself is fantastic. It is important and it is, as Dr Anita Lim, from King’s College London who is leading the trial puts it, a “game-changer”. However, the media coverage of this important trial leaves a lot to be desired.

The trial, funded by North Central and East London Cancer Alliance and supported by the NHS, is targeting people in parts of London who are behind on their cervical screening schedule. The goal is to provide access to screening for people who might otherwise miss it, for the varied reasons people delay, put off or otherwise miss their regular screening appointments. People who miss their screening opportunities are at a greater risk of developing cervical cancer than those who undergo their screening on schedule.

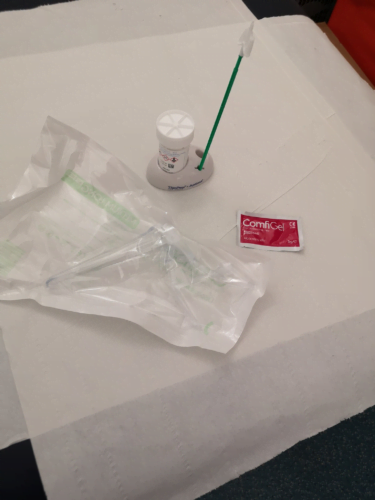

31,000 people will take part in this study, which involves providing participants (either through the post or from a GP practice) with an at-home swab, which they’ll then send off by post to be examined for the presence of a virus called HPV.

HPV and cervical cancer

Cervical cancer is almost always caused by infection with a virus called human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV is really common: most sexually active adults will encounter it in their lifetimes, some more than once. There are over 100 different types of HPV, of which 14 are linked to an increased risk of cancer. HPV spreads through genital contact including through the sharing of sex toys, or vaginal, anal or oral sex. HPV isn’t treatable, but in most cases, it doesn’t cause any problems and will clear up on its own within two years.

Simply having the virus does not mean you will develop cancer, but it does increase your risk of certain cancers. Think of how most floods might be caused by a leak, but not every leak causes a flood. The link is strong enough that testing for the presence of HPV can be a reliable screening tool to indicate the need for follow up testing to help prevent cervical cancer. If testing via cervical screening (either from a swab or from a smear) indicates that you have one of the high-risk for cancer types of HPV, further testing can be done.

Cervical screening

Currently, in the UK, if you are due to undergo cervical screening you will be invited to make an appointment for a cervical smear test. There are some reasons why you might not be automatically invited for a cervical smear test when needed, including in some instances if you are trans. So, if you think you should be having a cervical smear test and have not been invited for an appointment you should contact your GP practice. You should have cervical cancer screening if you have a cervix and are between the ages of 25 and 64.

A cervical smear test is a test where a sample of cells is taken directly from the cervix and sent off to a lab. In the lab, the sample is tested for the presence of HPV and, if the person is at risk for cervical cancer based on that test, the cells are examined under the microscope for changes that might indicate early signs of cancer.

HPV swabs

Taking a swab of the vagina is another way to test for HPV. Similar to the swabs we take for COVID-19, in this case a swab is run along the inside of the vaginal tract and sent to a lab for testing. If the person is considered at risk for cervical cancer, they will be invited for further tests to identify any cell changes that might indicate early signs of cancer. Public Health England suggests that self-testing for HPV using swabs might be an option for non-attenders but that the implementation of this requires assessing. That’s the purpose of this trial.

Swabs aren’t smears

So, the swabs aren’t smears, but who cares? As long as people get tested, what does it matter what we call it?

In covering this story, the BBC wrote:

“Smear tests: Women to trial ‘do-it-at-home’ kits for NHS” continuing to say that “About 31,000 women in London are being offered “do-it-at-home” tests to check for early warnings of cervical cancer, as part of an NHS trial.”

Meanwhile, the Independent repeatedly referred to the testing as a “home smear test”.

There are consequences to this messaging. Firstly, it gives the impression that what is to be conducted at home is a smear test, which this home testing isn’t. Smear tests cannot be conducted from home – they require cells to be scraped from the cervix, and it isn’t very easy to find your own cervix, nor is it easy to scrape cells from a cervix if you haven’t been trained to do it. It might not seem an important distinction – but examining those cells is how you tell if you have any pre-cancerous changes to those cells.

Detecting HPV in the vagina using a swab can tell you if you’re at risk of developing cervical cancer, but not whether you actually have any pre-cancerous changes. If people administering these tests are led to believe either that it’s the equivalent to a smear test or that it is able to detect cancer, what happens when they get a “positive” result? Do they then believe they have cancer? What are the potential consequences to that misunderstanding? At the very least we risk putting people under undue stress, anxiety and worry as they try to understand the result.

In reality, if you get a positive HPV swab result, it does not mean you have cancer, nor does it mean you will definitely get cancer. It just means there’s an increased risk, so you should get a smear test done as soon as possible.

There are other issues with the messaging too: if, as a result of these stories, people are led to believe that a cervical smear is so simple it can be self-administered from the comfort of your own home, there is a risk that people who would usually get their smear on time, but find it inconvenient and uncomfortable, instead decide to wait until the “home-smear” is available.

Might some people postpone their smear because they mistakenly believe self-testing is right around the corner? I hope not, but we do already know that there are lots of factors that play into delaying screening and I think it’s important to keep screening messaging accurate in order to prevent contributing to this.

This testing isn’t being made available for everyone – it’s currently being proposed as a solution specifically for people who are unable or unwilling to get a smear test. It is to catch the “non-attenders” who might otherwise go unscreened.

That is also important information. Many people are aware that there are issues of medical bias when it comes to health concerns that predominantly affect women, and this coverage has triggered concerns that this is a sign that the NHS is undermining women’s health care by transitioning to a screening option that relies on self-administration. This is absolutely not the case, there are no plans for self-administration for screening of cervical cancer to become the routine norm.

This is a contingency plan; a way to screen people who are not currently getting screened for cervical cancer.