This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 5, Issue 2, from 1991.

In 1895, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered X-rays, and shortly afterwards gamma rays and alpha and beta particles were first detected. These discoveries made researchers more willing to accept the existence of new forms of radiation. Without this openness the strange affair of N-rays might never have started.

One of the scientists conducting research into the properties of the newly discovered X-rays was Professor Rene Blondlot (1849-1930), head of the Department of Physics at Nancy University and a member of the French Academy of Sciences. He was a distinguished scientist and an expert in the physics of electromagnetic radiation. His research into whether X-rays were waves or particles (they are now known to be both), by seeing what effect polarised X-rays had on the intensity of a spark, indicated through the increased brightness of the spark that they were waves. But further tests showed that the radiation he was using on the spark could not be X-rays. He concluded that the cause of the visible change in spark brightness must be a new form of radiation which he was later to call N-rays, after the University of Nancy.

It was from this mistaken conclusion that the N-ray affair began. Blondlot next devised a series of increasingly sensitive experiments and devices for the detection of N-rays. The best of these involved phosphors, substances which emit light when struck by radiation. In early 1903, after he had investigated some of their properties, he published details of his discovery of N-rays. Soon experiments to detect N-rays were being performed by scientists all over the world.

While most researchers failed to detect N-rays at all, teams in France were discovering many unusual properties of the rays. Some substances opaque to visible light such as wood, paper and aluminium were found to be transparent to N-rays, and Blondlot even used aluminium prisms in his research. In contrast, water was found to be opaque to N-rays. The professor of medical physics at Nancy, Augustin Charpentier, discovered that N-rays were emitted by both living and dead bodies, and if shone on the eyes they improved a person’s ability to see in the dark. During 1904 an increasing number of scientific papers were published on N-rays and their properties.

Outside France, many leading physicists were unable to detect N-rays using Blondlot’s experiments. Some of these physicists met at the year’s meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and decided that one of them should visit Blondlot’s lab in Nancy. The physicist chosen was Robert W Wood (1868-1955), Professor of physics at Johns Hopkins University in the US and an expert in optics and spectroscopy. He was also the author of the humorous book How to Tell the Birds from the Flowers, and had in the past combated fraud by revealing that some spiritualists were fakes.

It was in September 1904 that Wood visited Blondlot’s laboratory. During his three-hour visit he was shown several experiments displaying various properties of N-rays, and he later described what happened in a letter to Nature (29 September, 1904). The first experiment involved the effect of N-rays on the brightness of a spark. Wood saw no difference between when the N-rays were concentrated on it and when his hand stopped them. He was told it was because his eyes were not sensitive enough.

Wood then asked the others to watch the screen upon which the light of the spark fell, and to say the exact moment when he blocked the rays. Not once were they able to correctly answer, despite having claimed that the change was distinctly noticeable. Next, Wood was shown photographic evidence of N-rays which clearly showed a difference in spark brightness. Wood saw that not only did the variability in spark brightness make accurate work impossible, but the manual control of the multiple photographic exposures was also a source of error. Knowing which photos were supposed to show N-rays, the operator could, in each exposure, unconsciously keep those photos exposed for a fraction of a second longer. At this point Wood still remained unconvinced. It was what occurred in the following experiments which convinced him N-rays did not exist

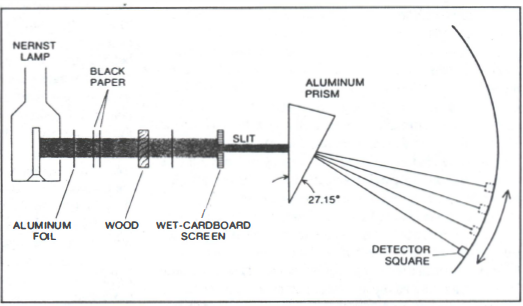

In a darkened room, Blondlot demonstrated how, with the use of an aluminium prism, a beam of N-rays could be separated into four beams of different wavelengths. These four beams were detected by moving a piece of cardboard with a phosphorescent strip painted down the middle along a curved steel support. Wood tried moving the detecting device along the curve but noticed no change in its brightness. While Blondlot prepared to take some measurements, Wood took advantage of the darkness to secretly remove the prism. Blondlot then took the measurements, getting the same values he normally got. Wood replaced the prism before the lights were turned back on. Next, Wood asked if he could move the prism so that Blondlot and colleagues could decide by the use of the detector if it was refracting the N-rays to the the left or the right. Three attempts were made but they were not correct, even once. They claimed that their failure was due to fatigue.

Finally, Blondlot showed Wood some experiments which showed how N-rays improved eyesight. He was taken into a room which was dimly lit so that the hands of a clock on the wall could not be seen. When an N-ray emitter (a steel file) was held close to a subject’s eyes, the subject claimed to be able to distinctly see the hands of the clock. After trying and failing to see any difference, Wood suggested a test. He chose when to move the file near the subject. Realising that the room was light enough for the subject to see when the file was being moved he secretly replaced it with a wooden ruler of the same size and shape which lay on one of the desks in the room. Despite the fact that wood was one of the substances unable to emit N-rays, the experiment was still a success.

Wood left Blondlot’s lab convinced N-rays did not exist, and that much of the evidence was purely imaginary. In his letter to Nature he described his visit and conclusions. This explained why so many top scientists had been unable to detect N-rays, simply because they did not exist, and it destroyed most of the support for N-rays outside of France.

Blondlot responded to Wood’s letter by increasing the accuracy of his experiments, but he still claimed to obtain successful results. During 1905, he and his supporters began to claim “it was the sensitivity of the observer rather than the validity of the phenomena that was called into question by criticisms like Wood’s.” Similar claims have been made in more recent times in paranormal research.

By this time in France, N-rays were also losing support because physicists had unsuccessfully tried to detect them using experiments like those suggested in Wood’s letter. In 1905, a French science journal published details of an experiment which would definitely show whether or not N-rays existed. Blondlot did not reply until 1906, when he refused to participate in such “a simplistic experiment … let each one form his own opinion about N-rays” he said.

And they did.