This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 5, Issue 2, from 1991.

A small, inexplicable scratching in the wainscoting of a house in Cock Lane, a narrow thoroughfare within the purlieus of Smithfield and the parish of the tolling of the hanging bell of Newgate Prison, was the modest herald of a curious case which was to blossom into a classic eighteenth-century enigma. All London was set, literally, by the ears by the escalating furore of rappings, crashings and scratchings perpetrated by an alleged spirit entity nicknamed ‘Scratching Fanny’. No less a personage than Dr Samuel Johnson was to set forth upon intrepid investigation and, in due course, pronounce the prankish poltergeist a great sham, and the whole paradox was to culminate in court, with a man accused of murder by a ghost defending his good repute by counter-charging criminal conspiracy.

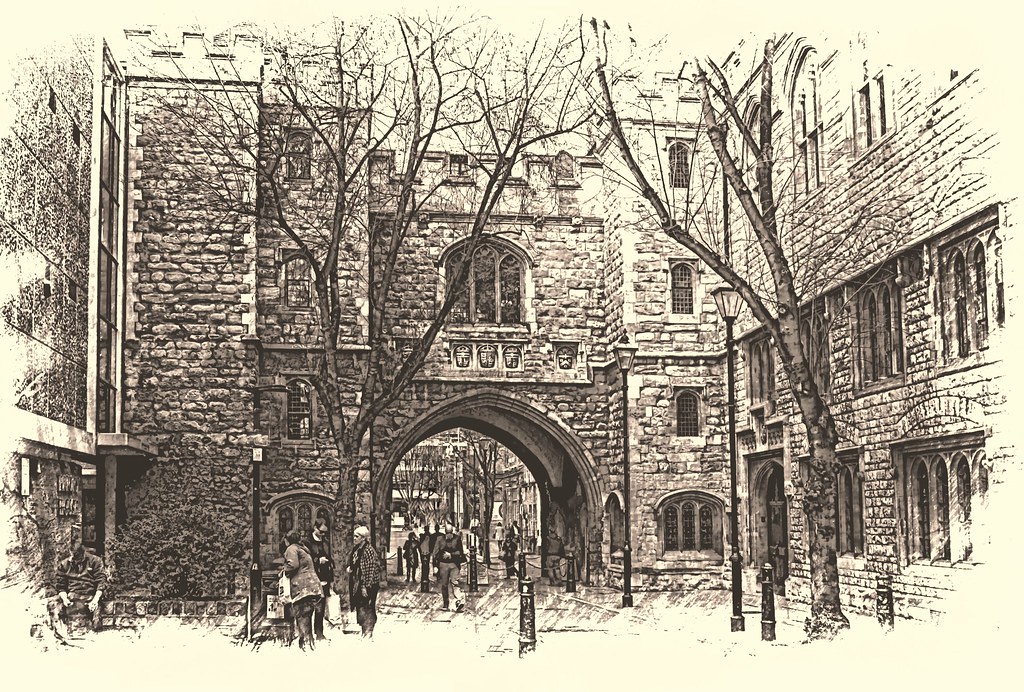

To unfold the origami-complex pattern of this ‘Cock Lane Tale’ we must travel first to Norfolk. There, in 1758, dwelt one William Kent, innkeeper and owner of the post office at Stoke Ferry, who, the previous year, had wed Elizabeth Lynes, daughter of a prosperous Norfolk grocer. Within 12 months she died in childbirth. Her sister, Fanny, who had come to tend her during her confinement, stayed on to look after the child, who soon died, and she remained with the widower. Predictably, they fell in love. Marriage was, however, out of the question. A deceased wife’s sister came within the forbidden degree of consanguinity. They decided to live together as man and wife, and, in October 1759, took lodgings in the Cock Lane home of Richard Parsons, officiating clerk of the church of St Sepulchre without Newgate.

In November, Kent had to attend a wedding in the country. While he was away, Elizabeth, Richard Parson’s ten year-old daughter, kept Fanny company, sharing her bed. And that was when, for the first time, the eerie scratchings and knockings were heard. Shortly after William ‘s return, the Kents left Cock Lane. Not only was Fanny by now a good six months pregnant and needing a house of her own, but bad feelings had blown up between Kent, who had lent Parsons, a feckless drunkard, 12 guineas, and Parsons, who having failed to make any effort at repayment, had been informed that the matter was in the hands of Kent’s lawyer.

On February 2, 1760, Fanny died, at the new house in Bartlet’s Court, Clerkenwell, of smallpox. She was buried in the vault of St John’s, Clerkenwell. In the course of the ensuing year William Kent did his best to put his twice shattered life back together. He set up in business as a stockbroker. He married again.

Meanwhile, at the house in Cock Lane the noisy manifestations had, after a lull, broken out afresh, the unquiet spirit which seemed to focus on and around the bed of little Elizabeth Parsons proving more boisterous than ever. Parsons called in a carpenter to dismantle the wainscoting. No down-to-earth explanation there. Turning his eyelids heavenwards, he humbly prayed the Reverend John Moor, assistant preacher at St Sepulchre’s, to bring his spiritual expertise to bear. A code of taps was introduced – one for yes, two for no, a scratching for displeasure.

By a system of leading questions, the entity was induced to state that it was the spirit of Fanny, that her ‘husband’ had poisoned her with red arsenic administered in purl (a popular restorative infusion of bitter herbs and ale or beer), and that she hoped he would hang! The spirit knocking while Fanny was yet alive was said to have been that of her sister, Elizabeth, warning her against Kent. It was a scenario which did not entirely displease the grudge-nurturing Parsons, and one, moreover, which it was his pleasure to bruit abroad. Neither was it exactly anathema to Fanny’s brothers and sisters, who were disputatious regarding her will, in which she had devised bar half-a-crown apiece to them – to William. A caveat was entered to prevent Kent from proving the will in Doctors’ Commons, but it stood legally invulnerable.

It was not until January 1762, that Kent saw an item in a newspaper, the Public Ledger, and became aware of the ‘phantastic’ accusation being levelled against him. Horrified by the public scandal, he went promptly to attend a seance at Cock Lane, and hearing the accusations rapped out, shouted angrily: ‘Thou art a lying spirit!’

In February 1762, the Reverend Stephen Aldrich, Rector of St John’s Clerkenwell, persuaded Parsons to allow his daughter, Elizabeth, to come to his vicarage to be tested by an ad hoc committee of learned investigators, including Dr Johnson. Fanny did not manifest. She had, however, previously promised to rap evidentially on her own coffin if at 1AM the investigators adjourned to St John’s vault. They did. She didn’t. Then… little Elizabeth was caught in the act of secreting a sounding board of wood in her bed. The Cock Lane Ghost collapsed amid widely echoed charges of fraud.

To complete his already partial vindication, William Kent brought, on 10 July 1762, the affair to the Court of Kent’s Bench at the Guildhall. On an information laid against them by William Kent, the Reverend John Moore, Richard Parsons, Mrs Parsons, Mary Frazer (who had acted as entrepreneurial ‘medium’ at Cock Lane), and Richard James (responsible for the prejudicial insertions in the Public Ledger) were charged with a conspiracy to take away Kent’s life by charging him with the murder of Frances Lynes.

The trial judge, Lord Mansfield, summed up for 90 minutes. The jury took a quarter of an hour to find all the defendants guilty. Moore and James were ordered to pay £588 to Mr Kent Richard Parsons was sentenced to two years imprisonment and three spells in the pillory. Mrs Parsons got one year, and Mary Frazer six months.

Parsons protested to the end that the knockings were genuine, and it must in all fairness be said that posterity has come to recognise that the Cock Lane manifestations did unquestionably bear the characteristic stigmata of similar outbreaks of poltergeistic infestation subsequently held by serious investigators of psychic phenomena to display the diagnostic hall-marks of paranormality.