Like the pop culture trope, the placebo effect has an ‘evil twin’. While the placebo effect is said to promote healing by influencing a person’s beliefs, the nocebo effect is claimed to harm through the same mechanism. Two sides of the same coin. Unfortunately, the evidence for a significant and consistent nocebo effect is just as flimsy as that for placebo.

This isn’t to suggest that the mind holds no power over the body. Our minds constantly influence our physical state; I can stand up and move simply by thinking about it. However, this does not imply that the mind’s ability to affect the body is boundless or largely unexplored. The contexts in which our minds exert control over our bodies are limited and typically mediated through nervous signalling or hormonal control.

When discussing the nocebo effect, the same handful of studies are frequently mentioned. One of the most prominent is the case study of the ‘placebo overdose’, published in General Hospital Psychiatry in 2007. In this paper, Reeves et al report on a 26-year-old man (referred to as Mr A) who arrived at the emergency room exclaiming, “Help me! I took all my pills”, before collapsing. Reeves notes that Mr A exhibited ‘rapid respirations’, appeared ‘drowsy and lethargic’, had a high heart rate (110 bpm), and very low blood pressure (80/40).

Doctors found an empty bottle of pills on him, labelled as part of a clinical trial for an experimental antidepressant. These were the pills that Mr A had taken; he denied taking anything else. Blood tests were conducted, revealing no evidence of paracetamol or aspirin overdose, and drug screening was negative. All other lab results were within normal range, including blood urea, nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolytes. The ER doctors gave intravenous saline to try and stabilise his blood pressure and, although it helped somewhat, his blood pressure remained low.

Four hours later, a doctor who was administering the drug trial arrived. He informed the attending physicians that Mr A was in the placebo group, and that the pills he had taken were fakes. Upon hearing this news, Mr A expressed surprise and ‘almost tearful’ relief. Within 15 minutes, he was fully alert, his blood pressure had stabilised at 126/80, and his pulse was 80.

For those worried for Mr A’s wellbeing, he was admitted to the psychiatric unit, and diagnosed with depression and dependent personality disorder. He was prescribed sertraline and psychotherapy, to which he responded well.

At first glance, the story of the ‘placebo overdose’ seems compelling. It also appears to directly contradict my view that placebo effects are generally limited to subjective reports, largely driven by things like confirmation bias and the subject expectancy effect. The Cochrane Review on placebo effects shares this stance: placebo effects do not manifest with objective symptoms.

In Mr A’s case, however, his symptoms were undeniably objective. His blood pressure and heart rate were measured, not reported. So, is this really a case of ‘placebos making you sick’?

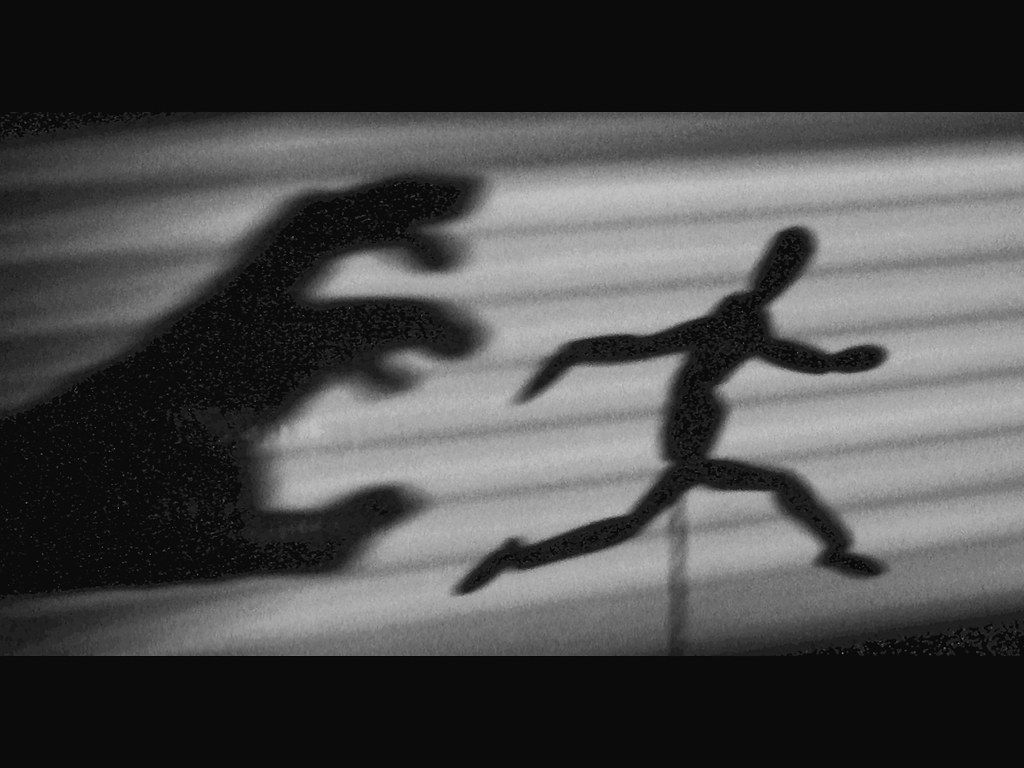

Don’t panic

The term ‘nocebo effect’ in this context is nebulous and mysterious: Mr A thought he was going to die, and so his body started to. When you die in the Matrix you die in real life; a demonstration of how the mind can affect the body. The mystery rather vanishes, however, when we simply reframe Mr A’s experience as a panic attack.

Mr A had a history with depression, having been prescribed amitriptyline when he was 22 years old. He stopped taking the medication shortly afterward, as he found the side effects intolerable.

In the weeks leading up to his admission to the ER, Mr A was again struggling with depression. During a particularly low and hopeless ebb, Mr A saw an advertisement for a clinical trial and decided to enrol, hopeful (one supposes) that this new antidepressant would result in fewer side effects than the amitriptyline.

During the first month of the trial, Mr A’s condition improved, but at the start of the second month, following an argument, he impulsively took all 29 remaining pills. He quickly regretted this and begged a neighbour to take him to hospital.

As panic set in, Mr A would start to hyperventilate, described by Reeves as ‘rapid respirations’. Hyperventilation increases blood oxygen but reduces blood carbon dioxide, leading to respiratory alkalosis, where blood pH rises. (This is also why cartoon characters breathe into a paper bag to calm down; it is a simple mechanism to prevent respiratory alkalosis by breathing more carbon dioxide!)

Respiratory alkalosis will cause peripheral vasodilation, an expansion of the blood vessels outside the heart, leading to a significant drop in blood pressure. Essentially, the same blood volume is now within a larger space, lowering the pressure. This also explains why Mr A’s lab results were normal, including for markers like creatinine and blood urea nitrogen. If, for example, the low blood pressure was caused by dehydration, these markers would be elevated. The intravenous fluids also had limited effect as the underlying issue was not blood volume depletion.

In response to the drop in blood pressure, Mr A’s heart would start to beat rapidly to try and compensate. This also then accounts for Mr A’s rapid heart rate, described by Reeves. Respiratory alkalosis will also induce constriction of the cerebral blood vessels, accounting for the reported drowsiness and lethargy, as well as his collapse. As Mr A experienced these symptoms, he likely interpreted them as signs of impending death, further reinforcing and exacerbating his state of panic.

Upon hearing the news that he had only taken placebos, Mr A would have calmed down. Once he stopped hyperventilating, his blood pH and blood pressure would quickly have returned to normal.

Perhaps it is reasonable to characterise this as a ‘nocebo effect’ or a ‘placebo overdose’, but I would argue that to do so is to lend undeserved credence to the power of the placebo. Mr A’s condition wasn’t the result of placebo administration. The objective symptoms reported were the result of hyperventilation, through well-understood and documented mechanisms. Scratching our chins and nodding sagely about the amazing power of the mind doesn’t explain anything, doesn’t reveal anything, and certainly doesn’t help people like Mr A.

Maybe a more valuable lesson we can take away from this case study is that panic attacks can be far more serious that we think, and those suffering them don’t just need to ‘pull themselves together’. And perhaps if Mr A’s doctors had recognised his condition for what it was sooner, he would have been spared those hours of pain, distress, and discomfort.