This story was originally written in Portuguese, and published to the website of Revista Questão de Ciência. It appears here with permission.

Disinformation is, in the strictest sense of the word, the composition and dissemination of information that is knowingly false or misleading with the aim of influencing individuals, groups or public opinion in favour of strategic, political, ideological, economic or even personal interests. It is not new for people, companies, institutions and governments to deliberately lie, whether to protect themselves, attack, discredit or hinder opponents and enemies, promote their agendas or obtain some kind of gain or profit.

There is no shortage of historical examples. From the Allied operations that helped convince the Nazi leadership that the invasion of Europe would take place through the Calais region in World War II, to the oil industry’s struggle to first deny the harmful effects on public health of adding lead to fuels, and then global warming and climate change, to the tobacco industry and the link between smoking and cancer.

Until recently, disinformation initiatives were laborious and slow. But today, with the internet and social media, lies travel at the speed of light, reaching well-defined target audiences with surgical precision, or as weapons of mass destruction of truth, credibility or public trust in people, policies or institutions. It is no coincidence that in recent years we have seen the rise of several anti-science movements, from the seemingly harmless flat-earthers to the clearly dangerous anti-vaccine movement, as well as the advance of radical ideologies, notably the far right, and religious fundamentalism.

In an attempt to understand this phenomenon, however, a new science has also emerged. It is called “Agnotology”, the study of the production and promotion of ignorance, of how people, groups, communities or even entire societies can remain or are kept ignorant or oblivious to certain information and facts, and the interests that this serves.

This field already has its researchers in Brazil, such as Nayla Lopes, a PhD student in Political Science at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG). As part of her thesis, Lopes seeks to establish a link between denialism in the Covid-19 pandemic and a deliberate promotion of ignorance in the government of former president Jair Bolsonaro.

“My goal is to study people’s denialist behaviour regarding the pandemic,” she says. “Before, I had the impression that there would be a limit to this behaviour, that ensuring the survival of oneself and those one cares about would outweigh this denialism. But what we saw was that this limit being repeatedly exceeded. People risked their own lives and the lives of those they cared about in the midst of one of the biggest health crises in history.”

Question of intention

According to Lopes, one of the biggest challenges of agnotology is to determine the intentionality of the spread of ignorance. Fortunately for her – and unfortunately for Brazil – the former president himself did not shy away from offering evidence of this in relation to the pandemic, with measurable impacts on the number of cases and deaths from Covid-19 in the country .

On more than one occasion, for example, Bolsonaro confessed that he was “the only head of state in the world” to have gone against the main recommendations of experts and health authorities to prevent the spread of the disease, such as social distancing. At the same time, there is no shortage of examples of the times he encouraged people to gather in crowds, some of them at the worst moments of the pandemic in Brazil, when the country was recording thousands of deaths per day. These were events in which he also made clear his opposition to the use of masks, another fundamental non-pharmacological measure to try to control the spread of the virus.

“By repeatedly saying that he was ‘the only head of state’ who was against these non-pharmacological measures and using this as a kind of ‘badge of honor’, Bolsonaro only gives more proof of his intention”, considers Lopes.

This also includes the discourse of minimising the health crisis, such as the many times the former president referred to Covid-19 as a “little flu” that could be easily cured by a non-existent “early treatment”.

“Who expects the president of a country to lie blatantly?” asks the researcher. “This type of minimisation by a person whom the public looks to for information and leadership fuels a tendency to calm down and become less alert at the individual level. Which, in the case of the pandemic, has made people even more vulnerable to the disease.”

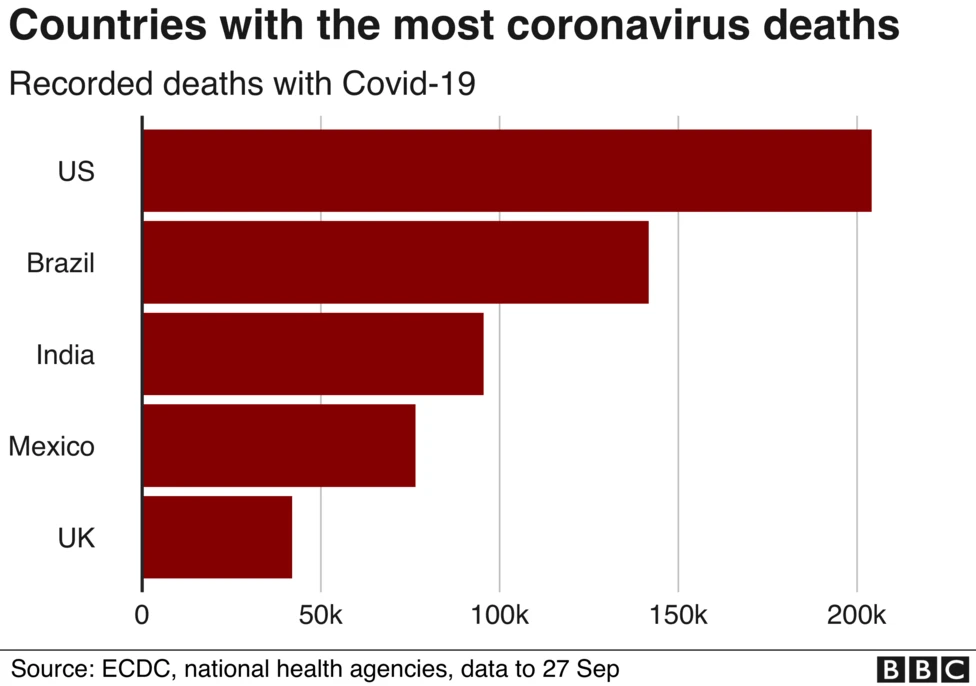

The result was a direct, and tragic, impact on pandemic statistics in Brazil: “It is no coincidence that we observed, for example, that places with a higher proportion of Bolsonaro supporters also had a higher mortality rate from Covid-19 .”

Furthermore, the former president did not act alone. It was not uncommon for Bolsonaro, members of his government, or his supporters to enlist supposed experts to try to legitimise his denialist discourse, in a typical disinformation tactic and further evidence of intentionality.

“When people first started talking about agnotology, the studies were about the tobacco industry and its strategy of spreading uncertainty and doubts about the relationship between smoking and cancer, the ‘merchants of doubt’ (a reference to the title of the book by science historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway on the subject),” Lopes recalls. “And experts play an important role in constructing this discourse. The tobacco industry funded studies to sow doubts about the scientific consensus, and the oil industry followed suit with climate change, in a format that seeks to bring scientific legitimacy to the agnotological discourse. During the pandemic here in Brazil, for example, we had the so-called ‘Doctors for Life’, a group that gained notoriety by prescribing useless ‘Covid kits’ and defending nonexistent ‘early treatment’.”

Lopes explained for those studying agnotology, the process of promoting ignorance, disinformation is key. And it can come in many forms, not necessarily lies, such as the straw man fallacy or anecdotal evidence, causing confusion in the public’s mind.

“There is no need to lie to present a denialist framework of reality,” she emphasises. “During the pandemic, for example, Bolsonaro said he took hydroxychloroquine and got better from Covid-19. But he could very well have taken nothing and got better, too. It is not a lie that he got better, but it changes the focus of the issue. Personal experience is not necessarily a lie, but it is incompatible with the scientific method. It is all part of the tactic of sowing doubt, and thus science is discredited by agnotological agents.”

Documentary evidence

Another important aspect of the work, says Lopes, is the collection of documentary evidence of the deliberate promotion of ignorance by these agnotological agents. In the cases of the tobacco and oil industries, history has shown how they accumulated knowledge about the relationship between their products with cancer and climate change, respectively, and their actions in an attempt to cover up or confuse the issue. The Covid-19 pandemic, however, is a recent event, which initially makes it difficult to study with the benefit of time and distance.

Once again, however, the former president, members of his government and his supporters made the researcher’s work easier, leaving many traces of denialist actions. Lopes recalls that, while in the first wave of the pandemic it was still possible to have doubts about the best strategy to face the health crisis, from mid-2020 and the beginning of the second wave of Covid-19, it was already established that hydroxychloroquine did not work against the disease, and the search for a supposed “herd immunity” was not only illusory but dangerous, with the potential to cause thousands of deaths and the collapse of health systems.

“There are more than a thousand warning documents ignored by the Bolsonaro government ,” she says. “From the second wave onwards, it was already possible to distinguish what worked and what didn’t in preventing the disease. Even without a vaccine, it was already possible to alleviate the situation with non-pharmacological measures. The information was available. So much so that Boris Johnson in the United Kingdom, and even (Donald) Trump in the US, in a way corrected the course. Bolsonaro insists to this day that he was right, even in the face of the tragic numbers of the pandemic in Brazil.”

The Brazilian Senate’s pandemic parliamentary inquiry also helped to accumulate documentary evidence about the denialist actions of the federal government and its supporters during the health crisis. Among them, Lopes cites the attempt to change the hydroxychloroquine package insert, discussed in a meeting at the Planalto Palace, and the “Brazil cannot stop” campaign, also conceived and implemented by the presidential office via the Presidency’s Communications Secretariat (Secom).

“The idea of all this was to mislead and confuse the public. There’s no way to say it wasn’t intentional”, he says.

Another example of this, the researcher adds, was the so-called Covid-19 “data blackout” promoted by the federal government. Back in June 2020, the Ministry of Health stopped releasing consolidated figures on the pandemic in the country, and then, forced by the Supreme Federal Court (STF) to provide the information again, manipulated the structure of the epidemiological reports to reinforce the government’s denialist discourse, such as with the decision to highlight the number of recoveries and minimise deaths. These decisions led Brazilian media outlets to join forces in a consortium to verify the information and ensure its credibility with the public.

“Information control is another aspect of this action. Not only the framing, but also the provision of basic information about the pandemic was neglected by the Bolsonaro government,” she says. “Even if people did not want to be guided by what political leaders said, they had difficulty informing themselves about the reality of the pandemic in the country so they could make their own decisions.”

Given this, Lopes believes he will have sufficient evidence to support the agnotological thesis of promoting ignorance in the Bolsonaro government that helped fuel the denialism of part of the Brazilian population in the face of Covid-19.

“Hydroxychloroquine, early treatment, herd immunity, people didn’t come up with these ideas alone,” she says. “Putting it all together, we have a very likely scenario of agnotological intentionality on the part of Bolsonaro, his government and supporters regarding the pandemic.”