Weird. It’s the word that’s defined the 2024 US presidential election. Democrats are experiencing unexpected success simply by pointing out how incredibly weird the right wing of American politics has become, and they’re not wrong:

There is a reason for the rapidly escalating weirdness of the American right that goes beyond the cognitive dissonance that comes of holding regressive views while society grinds slowly forward. The truth is that everything has gotten weird, because High Weirdness has gone mainstream, and the American right has it the worst.

In his book High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies, Erik Davis defines high weirdness as “a mode of culture and consciousness that reached a definite peak in the early seventies, when the writers and psychonauts… pushed hard on the boundaries of reality – and got pushed around in return.”

Davis attributes the term to Rev. Ivan Stang’s 1988 catalogue of strange stories, High Weirdness By Mail: A Directory of the Fringe: Mad Prophets, Crackpots, Kooks & True Visionaries.

High weirdness is fundamentally about skepticism of normie, mainstream beliefs and narratives. It arises from the often-accurate concern that those narratives are legitimising myths that suppress understanding and thereby allow dominant groups to maintain their power over society. The founders of high weirdness, who often called themselves psychonauts to emphasise their goal of exploring the uncharted spaces within their own minds, saw the world around them as asleep, and it was their obligation to wake everyone up.

In order to achieve their goal, the psychonauts sought to problematise all things normie through revelations of the weirdness that permeate our universe. For example, when he wasn’t busy cataloguing weirdness, Stang co-founded the Church of the SubGenius, a parody religion that overlaps significantly with Discordianism, an ironic cult that has significantly impacted internet culture. In fact, the counterculture author Robert Anton Wilson helped popularise both high weirdness and Discordianism through his conspiracy-based fiction, particularly The Illuminatus! Trilogy book series:

High weirdness has been mainstreamed through the adapting of weird stories from writers like H.P. Lovecraft and Philip K. Dick, as well as through the increasing popularity of science fiction more broadly.

The psychonauts of high weirdness were inspired by a blend of interconnected sources that all questioned dominant cultural narratives. The precursors to high weirdness include the cosmic horror of Lovecraft the Gnosticism of the Nag Hammadi, the psychoanalysis of Carl Jung, and the shamanism of indigenous and non-western traditions. To open their minds to the weird truths of the universe, the psychonauts were down to try anything, from Ayahuasca to Zoroastrianism.

The result was a lot of insight and a lot of harm caused by transgressive behavior in the name of seeking insight. Along with questioning taboos around drugs, the psychonauts questioned taboos around sexuality, which often resulted in pressuring people into sex they did not want (ie, rape). In their search for the truth, they contributed to the rise of drug culture, anti-government activism, and what we now ironically call the post-truth era.

You see, it’s tempting to think of modern skepticism as a reaction to the rampant spread of misinformation, but that oversimplifies the story. It’s more accurate to say that modern conspiracy theory culture and modern skepticism both arise out of high weirdness. As a result, both inherit a messy mix of reactionary attitudes, some progressive, others libertarian.

It’s the skepticism of high weirdness, combined with increased awareness of genuine conspiracies like Watergate, that has created the spaces in our society where conspiracy theories can now rage unchecked. High weirdness won the culture wars, but it came at a cost. Healthy skepticism about capitalist influences on medicine has given rise to alternative medicine as a commodified identity focused on resistance to “big pharma”. In seeking to challenge the narrowness of accepted scientific practices, the psychonauts pried open the pandoras box of pseudoscience and did everything they could to make woo sexy. Flash forward a few decades, and conspiracy theories now permeate our cultural landscape.

The psychonauts have managed to spread their doubting disposition through normie culture, bolstered by the tsunami of information and misinformation brought on by the internet, another child of high weirdness. It’s old hat now to talk about how the pioneers of the internet were often psychonauts, using psychedelics to try to break through their assumptions about how things had to be. Cliché as it is, it’s understandable that the experience of exotic states of consciousness could facilitate the construction of technologies for expanding and extending cognition, and lead to the disastrous motto of “move fast and break stuff”.

In trying to strip away the false assumptions of culture, high weirdness risks stripping our understanding down to nothing, until only nihilism remains. In this way, places like 4Chan and the nihilist black-pilled memetic cultures that fester in the dark corners of the internet, giving birth to QAnons, are also spawns of high weirdness. Everywhere, we see the tentacles of its skepticism altering our world and us with it.

Davis describes his account of high weirdness as a sort of “here be dragons” of the mind. Psychonaut exploration is valuable, but that exploration is always a tightrope between healthy skepticism and a spiral into unhealthy paranoia, between substance use and substance abuse, between the ethical violation of unjustified cultural norms and the horrors of moral nihilism. That is a difficult path to walk, and many of the protagonists of high weirdness like Philip K. Dick to Timothy Leary’s brother suffered from severe mental illness as a result of their drug use. When you take seriously the maxim “question everything”, it becomes dangerously easy to end up in a place where there is no such thing as truth or, even worse, a place where you’re confident you’ve found the hidden truth.

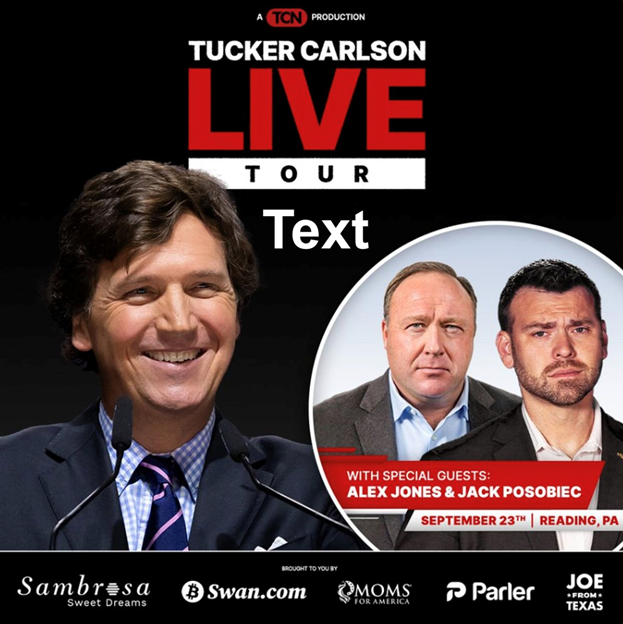

Which brings us back to the American right, a political movement drowning in conspiracy theories. How could it be that American conservatives, who notoriously would have loved the war on drugs even if it weren’t filling prisons with people of colour, have come to embody the radically anti-establishmentarian ethos of high weirdness? As with so much of high weirdness, the primary vector of transmission has been through radio and its digital offspring the podcast:

Promotional material for a Tucker Carlson live tour featuring Alex Jones and Jack Posobiec.

I’ve previously explained how Bill Cooper consolidated much of the libertarian conspiracy theorising that arose out of high weirdness, and provided the source material for a great deal of modern conspiracy mongering, including inspiring the work of Alex Jones.

Talk radio personalities like Limbaugh and Jones took the anti-governmental libertarian strain of high weirdness conspiracy theorising and stripped it of its psychedelic roots, repackaging it for conservative audiences by replacing the blunts and free love with cigars and misogyny. Gone was the talk of social progress, all of that was now part of the system that was controlling you and trying to keep you from returning to the glorious fictional past that fascists fantasise about.

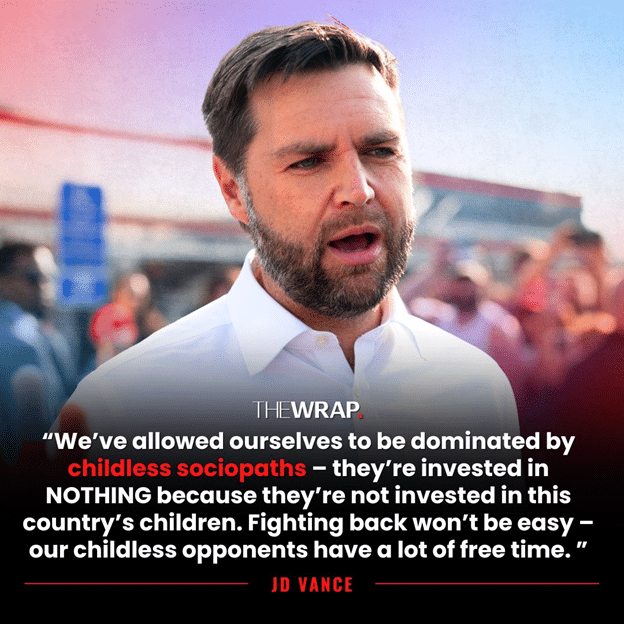

It wasn’t until Joe Rogan became the nexus of audio conspiracy mongering that the psychedelics roots re-emerged. It should come as no surprise that the worst quotes from J.D. Vance, prior to his attempts to instigate a pogrom, were all from him going on far-right podcasts to promote his Dark Enlightenment Catholic weirdness. At this point, in those spaces, anything is acceptable as long as it is framed as owning the libs.

That is how it is possible that a proudly adulterous billionaire reality TV star with an obsession for wrestling kayfabe seized absolute control of the GOP, instigated a violent insurrection through rampant conspiracy mongering, and still remains the Republican presidential candidate. It is why the most popular conservative news host in the country is openly promoting Holocaust deniers with zero repercussions. It is why the Republican presidential ticket will continue to promote racist blood libel style conspiracy theories about Haitian Americans long after it gets people killed.

Much of the problem arises from a mix of epistemic isolation and a wicked persecution complex. The American right has convinced itself that it is a marginalised community beset on all sides by the horrors of mainstream culture, with its theory of evolution and drag queen story hours. Unable to comprehend why they are increasingly perceived as extremely weird in all the worst ways, they have turned towards conspiracy theories to rationalise their losses and further enflame their base with nightmares of the coming multiracial transhumanist hellscape.

Not all blame for our current epistemic predicament falls on high weirdness. The capitalist mainstreaming and commodifying of high weirdness, the normalising of constructing one’s identity around the feeling of being abnormal, dilutes it down to the point where it is about as confronting as a Cronenberg body-horror soft-toy. Instead, high weirdness is now a fun shtick for performance artists like Joe Rogan. Rogan and many of the conspiracy theorists who orbit him, like Graham Hancock, can certainly ape high weirdness but they lack the training and rigor to stay on that epistemic tightrope, leading millions of followers with them as they fall into increasingly dark and dangerous places.

It’s especially depressing that capitalism has managed to swallow and digest high weirdness, since one of its best parts was the attempt to reverse the crisis of meaning that capitalism fosters for the sake of profit. For all its failings, high weirdness was an earnest attempt to fill the void many feel when confronted with an apathetic universe and a regressive society. They had the right idea, using a mix of materialism, mindfulness, and medications to counteract the capitalist mindfuck that equates happiness with endless consumption. Since capitalism can’t abide a threat, it’s unsurprising that high weirdness would end up enslaved to the status quo.

Ultimately, high weirdness is why it is so hard to fit any skeptical analysis into into neat, 1,500 word boxes. Davis calls high weirdness an “infectious project” and it certainly seems to infect much of what I experience. He meant that it’s impossible to study it and keep one’s distance, which has also been my experience, but I think it’s also true that the ideas of high weirdness have become highly infectious even to those who don’t study it. Without sufficient safety measures, that infectiousness has given birth to epistemic horror beyond human comprehension, which is how the GOP finds itself awash in not just climate skepticism and antivaxxerism, but blood libel and Holocaust denial.

Until they can find their way back to accepting at least some mainstream knowledge, they will remain dangerously weird: