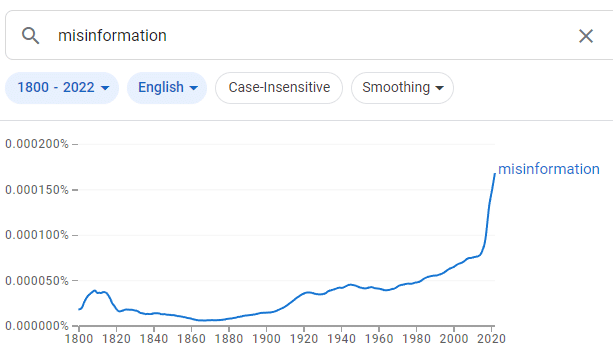

In recent years, there has been a surge in public discourse and academic research on misinformation. A search for the term “misinformation” on Google Ngram Viewer – a tool that tracks the occurrence of words and phrases in printed materials dating from 1500 to 2022 – reveals a sharp increase in its usage beginning in the early-to-mid 2010s. This upward trend shows no signs of levelling off, reflecting the still growing attention on this issue.

The rising interest in misinformation is not surprising considering its pivotal role in various tragic events in the last decade. In 2016, a man fired shots with an assault rifle at a pizzeria after encountering false stories claiming that Democratic Party leaders were running a paedophilia ring in the restaurant. In 2021, a mob stormed the US Capitol, resulting in several deaths and many more injuries, due to the unfounded belief that the 2020 presidential election was rigged against Trump. And in 2024, violent race riots broke out across England as a result of baseless claims that an attacker who had murdered three young girls was a Muslim asylum seeker (he was actually a British citizen born in Cardiff, Wales, to Rwandan parents). The list goes on…

To combat the negative impact of misinformation on society, researchers have developed interventions to help people detect false news. Among the most popular are inoculation interventions, which are based on the idea that misinformation is like an infectious disease. Much like a virus, misinformation spreads from person to person, and people become infected by misinformation much like they become infected by a disease. Inoculation interventions are described as metaphorical vaccines that deliver mental antibodies to fight and confer resistance against misinformation. They aim to do this by teaching people about manipulation techniques that are thought to be common in false news. The manipulation techniques that people learn about are considered weakened doses of attacking material that help foster immunity.

This biological analogy is appealing. It provides an easy way to conceptualise the issue of misinformation, especially given the Covid-19 pandemic. Indeed, both (mis)information and viruses are shared and propagated among people, making their comparison intuitively satisfying. It is therefore not surprising that the virus metaphor was also adopted by the World Health Organization, which describes too much false or misleading information during a disease outbreak as an ‘infodemic’. Nevertheless, as intuitive as it may be to use this epidemiological comparison when it comes to misinformation, there are concerns with its potential wider implications.

By likening misinformation to a virus, it is implied that we are all vulnerable to false news (albeit perhaps some people more than others) and in need of a psychological vaccine to resist its harmful effects. As a case in point, consider the following article titles: “We need to “vaccinate” people against misinformation so that they can identify suspicious information on their own” and “COVID-19 misinformation: scientists create a ‘psychological vaccine’ to protect against fake news”. This perspective paints a rather alarming picture, portraying people as passive and gullible consumers of (mis)information at constant risk of being misled. Is this accurate? Are people really at the mercy of misinformation unless they are immunised against it? Research suggests that this is not the case.

A recent meta-analysis with data from 193,282 participants across 40 countries and all seven continents showed that people are generally able to tell apart true and false news before experiencing any type of intervention. Accuracy estimates from our own work are as high as 79%, and we found that even when people think they are guessing, they can distinguish between true and false news with 67% accuracy. Moreover, other research suggests that most people are generally sceptical rather than gullible when navigating news on social media, which may be one reason that their ability to distinguish between true and false news is naturally quite good. Perhaps as a result of this scepticism, people report using various strategies to detect misinformation, such as fact-checking and relying on traditional fact-based media.

These data suggest that the average person is far from an easily deceived victim under the heel of misinformation. In fact, some researchers have suggested that the idea that people struggle to discern true from false information is a misconception and even a myth. Thus, the virus metaphor can not only be considered alarming, but also alarmist. Researchers have called for it to be abandoned completely, arguing that it is an oversimplified, incorrect, and ultimately misleading analogy.

But how do we reconcile these research findings with the real-world tragedies fuelled by misinformation? Well, it appears that certain groups of people are more vulnerable to believing misinformation than others. Factors such as conservatism and poor reasoning skills have been identified as contributing to this susceptibility. Note, however, that the susceptibility of conservatives to misinformation may be partially explained by the fact that widely shared false news tends to promote conservative positions. In line with this, the 2016 “Pizzagate” incident, the 2021 Capitol attack, and the 2024 England riots were all fuelled by right-wing misinformation and mostly carried out by individuals with far-right ideologies.

Therefore, while misinformation may not be an equally pervasive threat to everyone, it remains a significant issue, and there is still room for improvement. People are not perfect identifiers of misinformation, and there are individual differences in susceptibility to misinformation. Interventions could therefore be useful for boosting people’s ability to discern the veracity of news (which is already pretty good) even further, and targeting individuals who are most susceptible to misinformation. Ironically, using a virus analogy for misinformation, and thus a vaccine analogy for interventions against it, could alienate specific groups of people that may be most in need such interventions, such as vaccine sceptics.

In summary, it is not productive to use overextended, alarmist analogies that depict misinformation as a viral contagion that could infect anyone and everyone. Equally, anti-alarmist narratives should not be misconstrued to suggest that misinformation is not a problem – it is. There is a middle ground here, and to reach a consensus on the issue, we must view misinformation as the unique problem that it is, rather than relying on metaphors that provide an alluring but inaccurate perspective.