The Last of Us has become one of the most popular and widely discussed TV series of the last two years. Its post-apocalyptic horror and references to a pandemic event turned up just at the right moment, when the world was starting to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, and faced new crisis events. But, along with this fictional component, its scientific aspect has also attracted attention: it was the first time “zombie fungi” penetrated into popular culture so deeply.

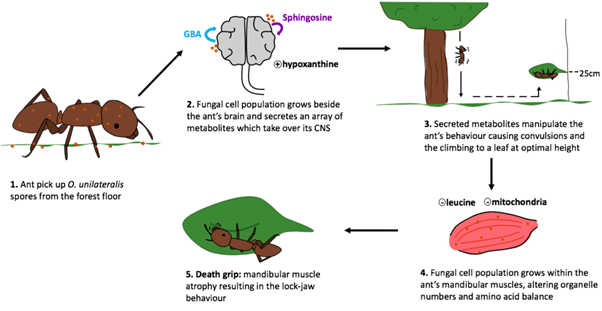

The main fungal character of this series is a Cordyceps fungus. In real life, fungi of this genus can alter the behaviour of infected insects, turning them into a kind of ‘zombie’ whose only purpose is to ensure the fungus’ spread. The show’s thrilling plot raises a question: could such a scenario happen to humans? Is there a possibility that one day, a fungus emerges that will transform the infected into aggressive monsters?

More than a year ago, The Skeptic featured an article by Natália Pasternak, a microbiologist from Columbia University. Natália argues that the ‘zombie fungus’ threat is only fictional – ‘zombie fungi’ in insects are highly specialised and interact with the host’s brain via an intricate set of chemicals. They are highly unlikely to jump to humans.

I fully agree with Natália, and could add that the phenomenon of behaviour-altering parasites is well characterised today. In humans, strong behaviour-altering action is exhibited by the rabies virus only. This virus makes its host aggressive and prone to bite, thus facilitating the spread of the virus through infected saliva. This is not a ‘zombie virus’, but our civilisation had gotten acquainted with it far earlier than we learned the word ‘zombie’. Behaviour-altering action is also suggested for Toxoplasma gondii – but, while it is well evidenced in mice, its effects are questionable in humans.

There is no evidence that any fungus can exert behaviour-altering action on humans. Moreover, there is no evidence for such an action in any vertebrate. Thus, I agree that the threat of being infected with a behaviour-altering fungus is negligible. But there is a real, conceivable danger to face new, emerging infections caused by fungi.

A more realistic fungal threat

Sixty five million years ago, a giant asteroid struck Earth, causing an effect comparable to a full-scale nuclear war. All large plants died at once due to an extreme blast of air and fire, and the planet was plunged into darkness by soot particles in the atmosphere.

In such harsh conditions, the biosphere turned into a “fungal compost”, says Dr Arturo Casadevall, infectious disease researcher. According to Dr Casadevall, this environment full of fungi made our small ancestors become warm-blooded. Most fungi are psychrophilic – this means they thrive in cool environments in relatively low temperatures, up to 30°C. Our body temperature of around 37°C grants us a narrow temperature barrier, just several degrees wide – that is unfavourable for most fungi. But, due to our warming climate, there is risk that things may change.

Fungi evolve rapidly and can easily adapt to observable climate change. The slow, degree-by-degree rise of global temperatures can shift their optimum temperature upwards – closer and closer to body temperature. If we lose our thermal barrier, we could be exposed to risks from a plethora of fungi that were previously innocuous to us.

This is not just theoretical speculation. The recent review in The Lancet Microbe cites some examples of fungal pathogens that have already shifted to humans from other habitats. The yeast Candida orthopsilosis, a human opportunistic pathogen, originated from a warm marine ecosystem. Fusarium oxysporum was a banana pathogen, but now it is becoming capable of causing infections in a number of human organs too, from skin to bones. Finally, the clinical strains of Candida auris – an emerging nosocomial pathogen – grow at higher temperatures than environmental strains.

It is possible that we are already facing the loss of our temperature barrier – and it is difficult to estimate which fungus is the next candidate to meet us. As a recent headline on Euronews pithily put it, our worst case scenario might be “The Last of Us minus the zombie part”.

The article by Natália Pasternak did mention these threats – but I feel compelled to put an additional emphasis on the real fungal threat. We should not be too calm. Instead of the fears of zombie disease, The Last of Us should be a promotion of knowledge about emerging fungal infections that are unfortunately underestimated, in contrast to viruses, for example.

What can we do? We need a system of tracking emerging and cross-kingdom fungal infections worldwide, to help us estimate and assess the danger. However, even that could be too late to stop the most detrimental events we might see unfold, since climate change cannot be reversed at once. This is one more reason to promote, invent and implement sustainable technologies right now.

Carbon emissions should become the problem for each of us – otherwise they will become the problem for the last of us.