Science communication is often about relating complex ideas in a clear and concise way. Unfortunately, the discourse around the placebo effect is anything but. The term ‘placebo effect’ is often used in casual conversation, popular media, and even academia as if it represents a single, well-understood phenomenon. In reality, ‘the’ placebo effect is a convoluted mess of unrelated effects that confound clinical trials.

For example, the National Institutes of Health in the US says the placebo effect works by ‘turning on the body’s natural mechanisms for helping us feel better.’ This statement is a gross oversimplification. Some placebo responses may be due to triggering the release of dopamine or endorphins, but not every placebo response can be chalked up to these mechanisms.

WebMD posits that ‘the placebo effect is due to a person’s expectations’. Again, this is not universally true. Beliefs and expectations can influence what patients report, but this does not account for all placebo effects.

The problem is that we use the same term, ‘the placebo effect’ to describe a wide array of phenomena, when the reality is that there is no singular effect. What we have instead is a morass of non-specific, inconsistent effects that confound clinical trials so perniciously they are often mistaken for clinical effects in their own right. They vary enormously depending on the context, and can include regression to the mean, experimenter bias, parallel interventions, classical conditioning, and more.

It’s like a magic trick. A good magician will have many ways to achieve the same effect. Something performed by sleight of hand in one show might be a stooge in another, or a camera trick or rigged prop in another. To the audience it all looks like the same trick, so we naively assume the trick is always performed the same way.

So when headlines appear claiming ‘We may finally know how the placebo effect relieves pain’ (New Scientist, 24 July 2024), we have good reason to be skeptical. There is no singular placebo effect, and no singular mechanism by which it modifies pain. Conditioning, bias, and mood can all influence reported pain to varying extents, and all are part of the placebo response. At best this discovery, whatever it is, may explain some parts of some placebo effects, but can we really say, ‘we finally know’?

What happened in the study

This particular headline was in reference to a recent study published in Nature titled ‘Neural Circuit Basis of Placebo Pain Relief’. The researchers divided twenty mice into two groups: a Test Group and a Control Group. The Test Group mice were placed into an apparatus consisting of two chambers, with distinct visual clues for the mice within each chamber. Over the course of three days, the mice were permitted to move between the two chambers as desired.

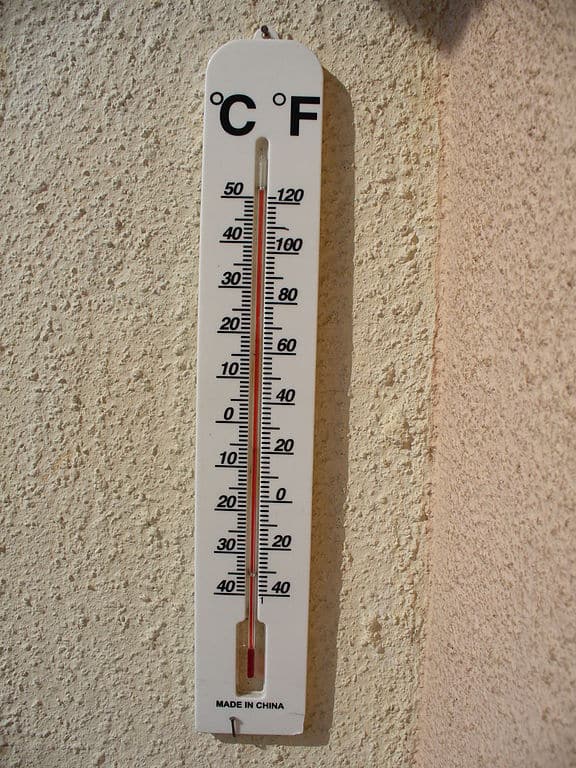

After three days, the researchers raised the temperature in one of the two chambers from 30°C to 48°C, which would have caused the mice some discomfort. They did this by heating the floor in the chamber, so the mice would suddenly have found the hot floor painful to walk on. This prompted nocifensive (nervous responses protecting against injury) indications of pain from the mice, such as licking their paws, jumping suddenly, or rearing up. The mice quickly fled to the second chamber, which remained at 30°C.

This was repeated for a further three days. The temperature in one chamber (always the same one) was increased to an uncomfortable level, so the mice fled to the other chamber. The researchers explain that the mice began to associate the second chamber with pain relief, as indicated by a reduction in nocifensive behaviours when in that chamber.

Meanwhile, the Control Group mice were left to roam both chambers without any temperature changes for all six days.

Finally, on the seventh day, the researchers set the temperature in both chambers to 48°C, making both chambers uncomfortable to be in. What they observed was that the mice from the Test Group fled to what had been the cooler chamber before, despite there being no temperature difference anymore. Mice in the Control Group showed no preference for which chamber they were in, and showed more nocifensive behaviours than the Test Group mice. The Test Group mice appeared to experience pain relief in the second chamber, even when it was just as uncomfortable as the first.

In a further test, the researchers administered naloxone, an opioid blocker, to a further set of twenty mice, before putting them through the same protocol. In this experiment, while the Test Group mice still fled to the second chamber on the seventh day, they did not exhibit fewer nocifensive behaviours. This strongly suggests that the pain relief observed in the previous experiment was the result of the release of endorphins. Endorphins that, in the second experiment, are prevented from working by the naloxone.

What it did(n’t) tell us

While this study is fascinating, it is far from a definitive explanation of the placebo effect, or even how placebo effects mediate pain. It is a clear demonstration of classical, or Pavlovian, conditioning. Classical conditioning probably does account for some of the placebo effects seen in some studies but many placebo effects, even for pain, have nothing at all to do with endorphins, naloxone, or conditioning.

The researchers also performed a slew of other experiments to identify neural pathways that we previously had not considered to be part of the endogenous pain relief mechanisms, and speculate that stimulating those pathways directly could induce endogenous pain relief (though I would add that a single shot of morphine will offer more pain relief than endorphins are ever likely to manage alone). One test confined the conditioned mice to a single chamber and observed that, in this case, their nocifensive behaviours were the same in both chambers, suggesting that perhaps the conditioned endorphin release was triggered by the pain itself rather than which chamber the mice were in.

Either way, headlines claiming ‘researchers explain how the placebo effect works’ are not only reductive but imply a singular mechanism where none exists. Much of the public confusion surrounding the placebo effect is rooted in this persistent oversimplification, which glosses over what is a complex set of phenomena.

The conditioning observed in these mice is a specific mechanism that might contribute to some placebo responses, particularly those involving learned associations. However, it is just one part of a much larger, more intricate picture that includes other effects like regression to the mean, reporting biases, parallel interventions, and so on.

Using a single term to describe all these distinct processes under one umbrella suggests a uniformity and simplicity that does not exist, and it muddies the waters of scientific communication. While this study is valuable, it should be recognised as one part of a much larger puzzle, not the definitive explanation of the placebo effect.