This article originally appeared in The Skeptic, Volume 4, Issue 1, from 1990.

Please note, as an archive article, some of the positions espoused here have been superseded by the evidence, and the piece is reproduced here as part our efforts to make available the history of the magazine. A follow-up piece, from the same issue, looked more closely and skeptically at the claims for the clinical use of hypnotherapy.

Many people, even with a quite educated background, still believe that hypnotism (or hypnosis as it is generally referred to nowadays) has something to do with the occult. When some people hear that I practise hypnosis, and research into it, they give some such response as “What, you actually do this sort of thing and it works?”

When they say ‘this sort of thing’ they wave their fingers in the air with a stroking motion which indicates the confusion in their minds, and indicates the main sources from which they have derived their stereotype of hypnosis.

Hypnosis has got nothing whatsoever to do with the occult, with parapsychology, with spiritualism, or with the huge body of confused belief that James Randi has so appropriately characterised as ‘flimflam’. This, of course, will be hotly contested by many enthusiastic practitioners and believers in the latter, and they have their own folk-lore of how telepathy, psychokinesis and such-like magic wonders can be assisted by hypnotising their subjects.

Let me first examine the basis for this belief and why even some seemingly educated people wave their fingers in the air when hypnosis is mentioned. Towards the end of the 18th century, Anton Mesmer, a Viennese physician, came to Paris and opened salons where he and his followers practised what they called ‘animal magnetism’, an art that had a notable success with people suffering from various disorders, notably those of a hysterical and psychosomatic variety.

Mesmer’s thesis was not entirely original, but he brought it up to date by expressing it in the more scientific terms of the Enlightenment, which superseded the religious terms of a previous age. What he practised was very much like the exorcism of religious healers like Father Gassner who had preceded him. He maintained that there was a universal fluid that he called ‘animal magnetism’, with which he and other favoured cognoscenti were richly endowed, and that they could convey it to their patients (whose animal magnetism was deficient and deranged).

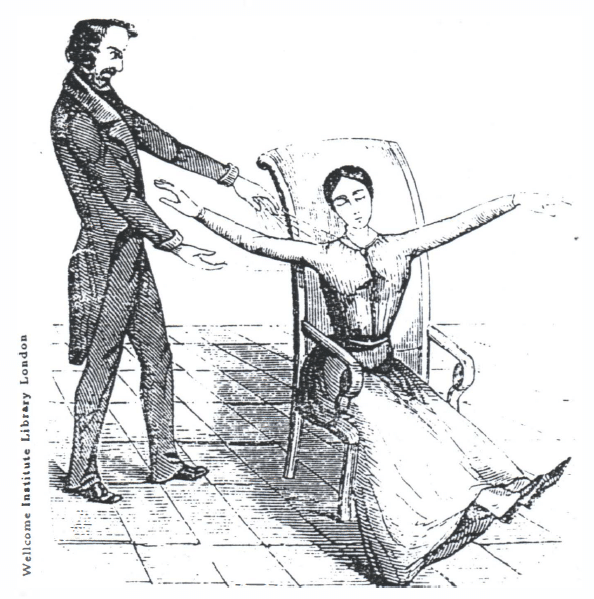

The waving of the fingers in the air relates to the supposed ‘magnetisation’ of patients by followers of Mesmer – mesmerists. The below illustration shows a 19th century artist’s impression of how a mesmerist operated, but it is quite inaccurate since the ‘passes’ were made either in light contact with the subject’s body, or very close. The stroking movement was after the model of stroking an iron bar with a steel magnet, and thus conveying the property of magnetism to the former from the latter.

Space does not permit the complexities of the career of Mesmer or an adequate account of the early mesmeric movement to be outlined here, but it must suffice to note that in the first half of the 19th century there was a flourishing mesmeric movement in most of the European countries and in the USA. This is dealt with in considerable historical detail by Ellenberger (1970) in his voluminous work, and in my own introductory text (Gibson, 1977) I try to trace the connections between mesmerism and occultism.

Mesmeric procedure certainly did have a beneficial effect on many sick people, and some eminent doctors, such as John Elliotson, embraced it. He introduced it into his practice at University College Hospital, an enthusiasm that eventually forced him to resign because of the opposition of the medical establishment. Almost any practice, however weird, will have a beneficial effect if it is applied by prestigeful doctors and believed in by trusting patients. This is the well-known placebo mechanism.

Good accounts of how mesmerism, in the later period, was actually applied, are given by Deleuze (1837) and by Esdaile (1852), and interested readers are referred to these original sources and warned that some contemporary writers are shockingly inaccurate in their descriptions of it.

But the mesmerists did not stop at trying to treat pain and disease. Many of them believed that they were possessed of miraculous power and were capable of producing all sorts of psychological and physical wonders. The mesmeric movement attracted every sort of crank, charlatan, and believer in the occult.

Using the sloppy sort of methods of inquiry that have always characterised the parapsychology movement, they convinced the gullible, and sometimes themselves, that they could teach people to see without the use of their eyes, transfer thoughts, prophesy the future and perform other forms of magic. Consequently, the pillars of orthodox medicine seized upon this all too blatant display of flim-flam, and refused to believe in some quite genuine cases in which severe surgical operations had been conducted painlessly.

When Dr Elliotson tried to present the case of a man whose leg had been painlessly amputated with the aid of mesmerism, many of his colleagues refused to listen, and one of them facetiously inquired if the man had yet been taught to read with the back of his neck, as this was a feat that other mesmerists had claimed.

But all sceptical doctors in the early 19th century were not so implacably unbelieving. Sir John Forbes (1845), although utterly contemptuous of the parapsychological aspect of the mesmeric movement and concerned to expose its charlatanry, gave a fair consideration to the considerable evidence that mesmerism was a genuine phenomenon and capable of producing an impressive degree of anaesthesia in certain circumstances. Testimony from such critics as Forbes is far more impressive than that from enthusiasts such as Elliotson.

Hypnotism is not mesmerism

In stating quite categorically that hypnotism should be distinguished from mesmerism I am aware that I differ in this from some quite eminent theorists. The difference is well put by Stam and Spanos (1982, pages 14-15) in the following passage:

the concept of hypnosis is, at best, vague and ambiguous and many of the behaviours associated with this label have changed quite substantially over the years… For most investigators the term ‘hypnosis’ refers to an ill-defined altered state of consciousness, the characteristics of which have never been clearly denoted or agreed upon… Moreover, there is little agreement as to variables that are necessary and sufficient for producing an hypnotic state. For historical reasons most investigators employ hypnotic inductions that consist primarily of verbal suggestions for relaxation and sleep… Some (Sheehan and Perry, 1976) argue that the largely non-verbal ‘passes’ made by Mesmer and his followers were variations of hypnotic induction procedures.

As I see it, we have much to gain in reserving the term mesmerism for the procedures that were fully described by the more literate of the 19th century mesmerists. It should be noted that these procedures relied on non-verbal manipulations, sometimes lasting for hours, and producing an unresponsive torpid state much resembling tonic immobility. By contrast, hypnotism is essentially a verbal procedure, the hypnotist suggesting ideas to the subject, and working upon the latter’s powers of imagination, to produce a state that may be very responsive and active, and , when well developed, has traditionally been called ‘somnambulism’.

We need not pursue the question of the differences between mesmerism and hypnotism any further here, except to observe that the two may exist coincidentally. An illustration in George Du Maurier’s famous novel, Trilby, shows Svengali making manual passes in the air in front of the girl, but he is also murmering “Maintenant, dors ma mignonne”, thus using a blend of mesmerism (inaccurately portrayed) and hypnotism – the verbal suggestion of sleep.

Some mesmerists undoubtedly used a measure of verbal suggestion, working on their subjects’ powers of suggestibility and fantasy, as well as immobilising them and lulling them with long-continued, rhythmic passes. What is evident, however, is that the evil reputation that was acquired by the mesmerists, a reputation for charlatanry and claiming occult powers, became attached to those who practised and investigated hypnotism from the earliest times.

Historically, the earliest hypnotist in the 19th century, in the sense of employing verbal suggestions to induce psychological changes, was the Abbe de Faria, whose book, published in 1819, rejected the whole mesmeric flim-flam of animal magnetism and sought to establish a sound psychological basis for his discoveries in hypnosis.

However it is to James Braid, a Scottish physician working in Manchester, that we owe the term ‘hypnotism’. At first he thought that the phenomena he induced were due to sheerly neurological mechanisms, and because of his ‘scientific’ stance and rejection of the mesmeric claims, he received a sympathetic hearing in at least some respectable medical circles. Later, he realised that really the hypnotic phenomena were due to psychological mechanisms, the suggestions of the hypnotist affecting a change in the state of consciousness of the subject.

His ideas were later taken up in France, and the patronage of such ideas by prestigious figures such as the great neurologist Charcot at the Salpetriere Hospital in Paris, and Bernheim at Nancy, made the topic of hypnosis relatively respectable in the medical and scientific world. But the mesmerists clung to their occult beliefs. At the International Conference on Magnetism in 1889 they emphasised that their master was the long-dead Mesmer, and that magnetism should not be confused with hypnotism.

Reasons for ultra-scepticism about hypnosis

When I was a lecturer in Psychology at Hatfield Polytechnic I continued my researches in hypnosis, researches I had begun in the 1950s at the Institute of Psychiatry. It was interesting to see the degree to which the public image of hypnosis had improved over the years and how the subject was gaining acceptance in orthodox Psychology.

Yet even so I still had fingers waved in the air by people who should have known better. At one time the rumour went round that I was conducting experiments in telepathy, and hence I had some difficulty in persuading a few students that I had no time for parapsychology malarky, and that I would not steal their minds away if they consented to be my subjects for hypnosis experiments.

It occurred to me, however, that in some quarters the misunderstanding was not wholly unintentional, for if you are engaged in boring experiments messing around with computers, or trying to get students to participate in dull experiments in psychophysics, a colleague engaged in highly interesting experiments in hypnosis excites envy. The students are only too willing to participate, so can it be wholly respectable? Does it not smell of the parapsychology game, ouija boards and table-turning?

It occurs to me that other psychologists have also encountered this difficulty. The great experimental psychologist Clark Hull made valuable advances in the investigation of hypnosis and suggestibility in the 1920s, yet when he obtained a new professorial chair at Yale, he had to give up his work in hypnosis research because of the extreme prejudice against the subject there. Hull wrote in 1933:

Such, in brief, is the history of hypnotism. All sciences alike have descended from magic and superstition, but none has been so slow as hypnosis in shaking off the evil associations of its origin.

Some practitioners of clinical hypnosis, of course, do not want to shake off the legacy of the past with all the associations with mesmerism and the occult , as they wish to appear as miracle-workers and mystery men. One such practitioner, who now has a huge and prosperous posthumous following in the ‘New Age’, was an American psychiatrist of the name of Milton Erickson. The late Dr Erickson rivalled the late Ron Hubbard in his pretensions, and followed the practice of Anton Mesmer in wearing purple, the colour of emperors and magicians (‘Principle 1. Wear lots of purple. All good Ericksonians know that it was Milton’s favourite colour because he was colour-blind except for purple. Also, all legitimate books on Erickson are bound in purple’, Chamberlain, 1988).

Many academic psychologists, anxious to pursue a respectable career in experimental psychology, have reacted and over-reacted to the supposed overtones of occultism in modern hypnosis, and leaned over backwards in their declared scepticism, so that many lay people are wondering whether the very topic of hypnosis is merely a con, and whether the concept should be relegated along with telepathy, psychic spoon-bending, dowsing, and a lot else, to the world of the flim-flam.

Thus Hearne (1982) argues that hypnosis is an umbrella term covering a whole range of known psychological phenomena, and that the concept has no scientific utility so the term should be abandoned. His main plank is that, in the psychological laboratory, by means of ‘task-motivating instructions’, we can get students to do the same things and report the same things without hypnosis as with hypnosis.

Another name for ‘task-motivating instructions’ is ‘intimidation’. This really relates to some old psychological experiments by Asch (1958) who showed that if you rigged the laboratory situation sufficiently you could compel many laboratory subjects to deny the evidence of their senses and report just about anything you wanted them to report, and the experiments of Milgram (1963) in which some fairly normal people were intimidated into doing some highly abnormal things in the supposed infliction of pain on others.

Such experimenters do not face the fact that people may say and do the same things for totally different reasons. A student may report that he felt no pain in a laboratory experiment either (a) because a negative hallucination for pain had been induced by hypnotic suggestion; or (b) because he’ll get in the professor’s bad books if he does admit that it hurt a bit, and thus spoil the professor’s hypothesis.

It should be noted that although Hearne, writing in 1982, supported his article by 15 published studies, none of them is later than 1967, with the exception of two articles by himself and with a colleague. His paper was old hat. The peak of this ultra-scepticism came at the end of the 1960s with the publication of a book by T.X. Barber (1969). Barber was, at that time, the Big Bad Wolf of the hypnosis world, the Ultra Skeptic No. 1. He has softened since, and twenty years later seems to admit that hypnosis is, after all, a useful concept.

But there have been many contenders for the mantle of Barber and the title of the Ultra Skeptic No. 1. Graham Wagstaff, an ex-collaborator of Hearne’s, published a book in which hypnosis was more or less equated with compliance, and in his book he cited T.X. Barber 213 times! Wagstaff’s book is interesting in that he presents his case like a very good barrister presenting a highly dubious case, yet seeking to implant in the minds of the jury sufficient suspicion that will eventually be developed into certainty that the accused was (or was not) guilty. With regard to compliance, early in the 1982 book, page 55, he writes:

In this chapter examples have been given to illustrate the importance of compliance in determining hypnotic behaviours. However, as the final study seems to indicate, there appears to be more to certain reports by some subjects than compliance; it appears that some subjects may genuinely believe themselves to be, or to have been, in a special condition or state of ‘hypnosis’.

Of course these subjects are mistaken about themselves, Wagstaff proceeds to show, for as he sees things, there is no such thing as a special condition or state of ‘hypnosis’. And having given this cautious caveat, he goes on throughout the book to demonstrate that all the phenomena of hypnosis could be explained in terms of compliance, and so the ultra-sceptical layman who thinks that the hypnotic subject is just doing as he is told, may well be right!

The latest contender for the mantle of Barber (1969) and the title of the Ultra Skeptic No. 1 is Nicholas Spanos at Carleton University. Spanos has even gone the length of devising his own scale for measuring hypnotic responsiveness – there were already quite a few well-known and widely used modern scales published, but they did not suit Spanos’ special requirements. And what are these requirements? Let me quote a published commentary on Spanos’ creation, the Carleton University Responsiveness to Suggestions Scale (CURSS) from Kihlstrom, 1985, page 387; emphasis added*:

Recently, Spanos and his associates introduced the Carleton University Responsiveness to Suggestion Scale (CURSS; Spanos et al 1983c,d)… While the CURSS clearly taps the domain of hypnosis to some degree, it also tends to define hypnosis in terms of the subject’s willingness to cooperate with the procedures rather than in terms of subjective experience, as is characteristic of the Stanford scales.

Enough said. Recently Spanos contributed an article to the Skeptical Inquirer (Spanos, 1987-88) in the course of which he set out his own theory of hypnosis and made what were, to my mind, certain misstatements of fact.

I therefore wrote to the SI pointing out that another writer had correctly identified at least seven other respected theories of hypnosis that are accepted by the scientific community, and that Spanos’ theory was not the only acceptable one, as readers might suppose. I also called attention to a misstatement of fact that he had written, and pointing out that the position that he takes “has finally been abandoned by most serious research scientists”.

My letter (Gibson, 1988) was published alongside a reply from Spanos, in the course of which he writes, “According to Gibson, this position has been abandoned ‘by most significant research scientists’. Unfortunately Gibson never tells us who these scientists are or what evidence led them to abandon this position.”

Unfortunately it would take up many pages of space to name all these scientists, and to cite all the published studies; indeed many significant scientists researching in the field of hypnosis have never held this position in the first place. However, it is up to me to let readers know just who the scientists are and where their arguments can be read in a concise form, if readers are interested. Fortunately, this task is easy. I would refer readers to the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences 9, pp. 449-502; (1987) 10, pp. 519-529; pp. 773-76; (1988) 11, pp. 712-714.

Spanos writes the initial article, but this is followed in the same issue of the journal by no less than 22 contributions from other scientists, some of them highly critical of Spanos’ work, and charging him with failure to cite all the relevant evidence, and themselves providing many additional references relevant to the controversy that Spanos had not mentioned. The controversy continued in the 1987 and 1988 issues of the journal that I have mentioned, 12 more protagonists leaping into the fray!

The dangers of ultra-scepticism

I am a highly sceptical person myself, and concerned about all the rubbish, codswallop, half-truths and sheer lies about hypnosis that the public is being fed with, mostly by interested people who aim to make a living out of it by preserving the occult aura that has bedevilled it for so long.

Why then, should I object to the ultra-sceptics’ efforts to debunk it completely out of existence? As I see it, by leaning too far over backwards and reinforcing the view held by some laymen that ‘It’s all a con’, they do, in fact, play into the hands of those who are anti-science and gleefully proclaim that as scientists can’t agree, maybe the occultists were right and it’s all a question of mysterious fluids of animal magnetism.

I do not claim that we know all about hypnosis; I have been researching in the area for thirty years and there are still mysteries about it that still amaze me, but I also know that considerable progress has been made by applying the methods of natural science in its investigation, and I am optimistic enough to expect that we shall continue to make progress.

Let me end by quoting the great ex-Ultra Skeptic No. 1, T.X. Barber, who ended his 1969 book thus on page 242:

Although research in ‘hypnosis’ promises to provide a broader understanding of human behavior, the reverse is also true – as psychologists working on other topics develop general principles, their principles should help us attain a deeper understanding of the topic ‘hypnosis’. Finally, the topic ‘hypnosis’ may lose all of its aura, mystery, and separate status and become integrated into general psychology.

I agree with him there.

References

- Asch, S.E. (1958), Effects of group pressure upon modification and distortion of judgements. In E.E. Maccoby & E.L. Hartley (Eds.) Readings in Social Psychology, (3rd Edition) New York: Halt, Reinhart & Winston.

- Barber, T.X. (1969), Hypnosis: A Scientific Approach. New York: Van Nostrand Reinholt Co.

- Chamberlain, L. (1988), How to be an Ericksonian (Milton not Erik). Swedish J. Hypnosis, 15, 128-130.

- Carli, G. (1978), Animal hypnosis and pain. In F .H. Frankel & H.S. Zamanski (Eds.) Hypnosis at Its Bicentennial, New York: Plenum Press.

- Deleuze, J.P.F. (1937), Practical Instructions in Animal Magnetism, (Trans. T.S. Harshorn) Providence R.I.

- B. Cranston & Co. Ellenberger, H.F. (1970), The Discovery of the Unconscious. New York: Basic Books.

- Elliotson, J. (1843), Numerous Cases of Surgical Operations Without Pain in the Mesmeric State, London

- H. Bailliere. Esdaile, J. (1952), The Introduction of Mesmerism as an anaesthetic and Curative Agent into the Hospitals of India, Perth

- Dewar & Sons. Forbes, J. {1845), Mesmerism True – Mesmerism False, London: J. Churchill. Gibson, H.B. (1977), Hypnosis: Its Nature and Therapeutic Uses, London

- Peter Owen. Gibson, H.B. (1988), Understanding hypnosis. Skeptical Inquirer, 13, pp. 106-107.

- Hearne, K. (1982), A cool look at nothing special. Nursing Mirror, 20 January Hull, C.L. (1933), Hypnosis and Suggestibility: An Experimental Approach, New York

- Appleton Century Crofts. Kihlstrom, J.F. (1985), Hypnosis. Ann. Rev. Psychol., 36, pp. 385-418

- Melzack, R. & Wall, P. {1966), Pain mechanisms: a new theory, Science, 150, pp. 971-979.

- Milgram, S. (1963), Behavioral study of obedience. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol., 67, 371-378.

- Spanos, N.P. (1987-88), Past-life hypnotic regression: A critical review. Skeptical Inquirer, 22, 174-180.

- Stam, H.J. & Spanos, N.P. (1982), The Asclepian dream healings and hypnosis: a critique. Int. J. Clin. Exper. Hypnosis, 30, pp. 9-22.

- Wagstaff, G.P. (1982), Hypnosis, Compliance, and Belief, Brighton: The Harvester Press.

*Note: emphasis added to this quote seems to have been lost in converting the archive article to its digital format.