Last weekend, I went to the UK Athletics Championships in Manchester, which means I spent the whole day watching elite athletes doing a range of activities from jumping (high, long, over hurdles or with a pole), to throwing heavy things like javelins, discuses, hammers and shotputs, and running at a variety of speeds across a range of distances. It also means I spent the majority of the day snacking – pre-prepared sandwiches, Babybel cheeses, those little vegetarian scotch eggs, and fondant fancy cakes.

If you watch the women’s javelin on BBC iPlayer from the Saturday morning, you’ll probably spot me eating. And if you’ve been paying any attention to half the UK media over the last year or two, you might be completely aghast at that snacking range, given that they were things that would be classified as Ultra-Processed Food.

Ultra-processed food has been having a MOMENT these last few years. We’ve seen headlines like,

- “Ultra-processed foods need tobacco-style warnings, says scientist” from The Guardian

- “Ultra-processed foods are killing millions – here’s how to avoid them” from The Independent

- “Ultra-processed foods should be banned in schools and hospitals to stop them ‘pushing aside’ more nutritious alternatives, leading researcher says” from The Daily Mail

- and “Ultra-processed food linked to 32 harmful effects to health, review finds” from The Guardian again.

Even the religious have got in on the act, with an article from PremierChristianity.com headlined “Your body is a temple. So should you join the war on Ultra Processed Food?”, which concludes:

“Even if the arguments do contain some inaccuracies and over-simplification, there’s a prevailing sense that UPF isn’t just bad for the body, but also the soul.”

So I know what you’re asking yourself – what is this demon food that has Christians and the mainstream media alike fearing for my eternal soul, and why are we only starting to hear about it now?

What are ultra-processed foods, or UPFs?

The idea of ultra-processed foods isn’t entirely new – the concept was first described in 2009 by a researcher and his team from Sao Paulo, Carlos Monteiro. In an article published in Public Health Nutrition he outlined three types of food. Group one included minimally-processed foods, or “whole foods that have been submitted to some process that does not substantially alter the nutritional properties of the original foods which remain recognisable as such, while aiming to preserve them and make them more accessible, convenient, sometimes safer, and more palatable.” The kind of processing group one foods might have undergone includes things like cleaning or cutting, and pre-cooking.

Then we have group two, which are “substances extracted from whole foods. These include oils, fats, flours, pastas, starches and sugars… Traditionally they are ingredients used in the domestic preparation and cooking of dishes mainly made up of fresh and minimally processed foods.”

Finally, according to Monteiro, we have the third group of foods: ultra-processed foods. “These are made up from group 2 substances to which either no or relatively small amounts of minimally processed foods from group 1 are added, plus salt and other preservatives, and often also cosmetic additives – flavours and colours.” This category includes breads, biscuits, crisps, and cereal, plus meat products like chicken nuggets or hot dogs.

Monteiro’s is not the only definition of ultra-processed foods currently in use. In 2019, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations put together a document titled “Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system”. Carlos Monteiro was actually one of the authors of this document. It defines four categories of food: Unprocessed and minimally processed foods, Processed culinary ingredients, Processed foods and Ultra-processed foods. It says:

“Some common ultra-processed products are carbonated soft drinks; sweet, fatty or salty packaged snacks; candies (confectionery); mass produced packaged breads and buns, cookies (biscuits), pastries, cakes and cake mixes; margarine and other spreads; sweetened breakfast ‘cereals’ and fruit yoghurt and ‘energy’ drinks; pre-prepared meat, cheese, pasta and pizza dishes; poultry and fish ‘nuggets’ and ‘sticks’; sausages, burgers, hot dogs and other reconstituted meat products; powdered and packaged ‘instant’ soups, noodles and desserts; baby formula; and many other types of product.”

Its definition for what constitutes an ultra-processed food is very long and very technical, but it includes the following:

“Formulations of ingredients, mostly of exclusive industrial use, made by a series of industrial processes, many requiring sophisticated equipment and technology (hence ‘ultra-processed’). Processes used to make ultra-processed foods include the fractioning of whole foods into substances, chemical modifications of these substances, assembly of unmodified and modified food substances using industrial techniques such as extrusion, moulding and pre-frying; use of additives at various stages of manufacture whose functions include making the final product palatable or hyper-palatable; and sophisticated packaging, usually with plastic and other synthetic materials…

“Ingredients include sugar, oils or fats, or salt, generally in combination, and substances that are sources of energy and nutrients that are of no or rare culinary use such as high fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated or interesterified oils, and protein isolates; classes of additives whose function is to make the final product palatable or more appealing such as flavours, flavour enhancers, colours, emulsifiers, and sweeteners, thickeners, and anti-foaming, bulking, carbonating, foaming, gelling, and glazing agents; and additives that prolong product duration, protect original properties or prevent proliferation of microorganisms.”

Meanwhile, the UK Food Standards Authority, says of UPFs:

“There is no single, universally agreed definition for ultra-processed foods. The NOVA classification (which is the most commonly used) talks about food which contains “formulations of ingredients, mostly of exclusive industrial use, typically created by a series of industrial techniques and processes.”

This is a problem – it is very hard to study something that you can’t adequately define. It’s even harder to communicate risk to the public when even experts struggle to define the topic. What’s more, oversimplification really doesn’t help.

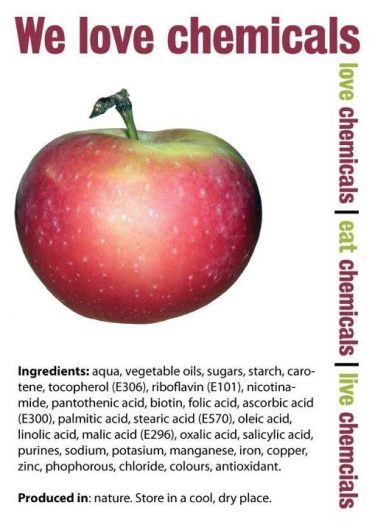

Food is complex. There is nothing simple about anything we eat. We’ve all seen the meme showing the list of chemicals that we find in the humble apple – chemicals that occur naturally, to be clear.

I’d like to be able to tell you that nobody is claiming apples are unhealthy, but in our social climate with its dizzying array of comments and opinions around nutrition, “health”, body size and diet, there are definitely people who will tell you eating fruit is unhealthy. But not even those people can deny that an apple is a whole, unprocessed (or minimally processed, if you include washing) thing you can eat.

What constitutes ‘processing’?

Processing food is also complex. Taking that apple and cutting it into slices is processing. Taking those apple slices and coating them in lemon juice to prevent browning is adding a preservative – processing. Each step is a process, but our apple is still there.

One of our great evolutionary leaps can be attributed to our ability to process foods. In a National Geographic article on the evolution of the human diet, Harvard primatologist Richard Wrangham argued:

“…the biggest revolution in the human diet came not when we started to eat meat but when we learned to cook. Our human ancestors who began cooking sometime between 1.8 million and 400,000 years ago probably had more children who thrived, Wrangham says. Pounding and heating food “predigests” it, so our guts spend less energy breaking it down, absorb more than if the food were raw, and thus extract more fuel for our brains.”

Even those who warn about the dangers of ultra-processed foods recognise that ultra-processing isn’t simply about super modern industrial processing of foods. That document from The Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN explains:

“Not all ultra-processed foods are recent or new. The first such products created and enabled by mass industrialisation, some commonly consumed for generations, include packaged cookies (biscuits), preserves (jams); sauces, meat, yeast and other extracts; ice-cream, chocolates, packaged candies (confectionery); margarines; and infant formulas.”

The science on UPFs

So what does the science say? There have been a couple of high-profile studies reported recently that suggest ultra-processed foods are linked to poorer health outcomes, though there are some significant concerns with some of those studies. Eating a diet high in ultra-processed foods is probably linked to some poorer health outcomes, but the studies don’t adequately control for other causes.

One such cause is poverty – we know that poverty is associated with poor health outcomes, and we also know that people living in poverty are more likely to eat UPFs. There are many reasons for this. It might be because they’re working multiple jobs and just don’t have time to cook a meal from scratch – ready meals are ultra-processed, but they are also often packed with a range of macronutrients (carbs, protein, fat, vegetables), and are quick to prepare.

It might be to do with associated costs – cooking from scratch requires a kitchen, a fridge and/or freezer (plus the electricity to run it) to store ingredients, a microwave/oven/hob/air fryer plus the power to run them, pots and pans and other cooking utensils, the main ingredients themselves, plus any other ingredients needed for the cooking process, like oil. Only some people in poverty have access to all of those things.

It might be due to disability, which makes chopping, standing to stir a pot or bending to put something in the oven difficult. Or it might simply be because they’re feeding multiple kids with different food preferences and don’t have the energy to make eating healthy food over palatable food the battle of that day. Or they might be a carer and spend all their energy preparing a meal that their dependent is able to eat and then don’t have the energy or appetite to cook something for themselves.

People in poverty often rely on – or in some cases, resort to – ultra-processed foods, and demonising or banning those foods (as some of those headlines and ‘experts’ suggest) is not the solution to that problem. Solutions to that problem are challenging and require policy, welfare and structural change. Telling individuals that UPFs are bad for them will only make them feel worse about choices they have little to no control over.

Another potential reason ultra-processed foods might be linked to poorer health outcomes is their levels of energy-dense ingredients, which are high in calories but low in nutrients. This isn’t in and of itself a bad thing, but if we are regularly consuming energy-dense foods, we can find ourselves getting hungry quicker, and eating more of those foods to feel sated. This can lead to a high intake of certain types of food. Balance is key when it comes to diet, so over-reliance on one type of food can increase our risk of poor health outcomes. It is easier to inadvertently eat a large proportion of energy-dense foods when consuming ultra-processed foods. None of this has anything to do with how many processes the food has undergone along the way.

In fact, a study published last year titled “Dietary Guidelines Meet NOVA: Developing a Menu for A Healthy Dietary Pattern Using Ultra-Processed Foods” showed that is entirely possible to develop a menu where over 90% of the calories come from UPFs but the overall diet has “a high diet quality score, and contain adequate amounts of most macro- and micronutrients,” with a healthy eating index score of 86/100.

The science is currently far from settled. We don’t have good evidence that any negative findings around ultra-processed foods are actually due to the fact that the foods had been “ultra processed”, rather than other confounding factors, and even if they were to prove that UPFs were the issues, we would still have no idea what the culprit might be. Meanwhile, we wade through daily headlines in which UPFs are demonised – far before there’s evidence to justify such negative press around an entire group of foods.

We have to be careful here, especially in the communication around the proportional level of fear the public should have. Should we be telling the public that we shouldn’t bake our own bread at home, because after all, yeast is ultra processed? Or, given that infant formula is classified as UPF, should we be discouraging bottle feeding and instead bringing back wet nurses? The panicked headlines need to be put into context and need to be led by the evidence, not by fear.

Fearmongering and food anxiety

The fearmongering is what worries me most about the constant discussion around ultra-processed food. There is absolutely no escaping it. It’s already leading some people to experience serious food anxiety. Just take a look at Reddit’s r/UltraProcessedFood, which has 23,000 followers, and is filled with people sharing labels of individual food items to ask if they are ‘safe’ to eat.

One Reddit user explains that they used to drink fruit cordial, but then they found out that it’s ultra processed, so now they’re adding whole fruit to their water… but now they’re worried that they’re consuming too much sugar by doing this. Another asks whether passata (pureed, strained fresh tomatoes) is ultra processed, because it contains citric acid – a chemical found naturally in all citrus fruits. Another person asks “I use this [canola oil spray] every day to make a large omelet. How screwed am I?” Fortunately, most of these threads have some responses from people reassuring those users that their anxiety around food is more dangerous than the food item itself – but it illustrates how much fearmongering can affect people’s experience of nourishing their body.

Not everyone listens to those reassuring voices. Orthorexia nervosa (ON) was first described in the late 90s, which the Association of UK Dieticians defines as an eating disorder where:

“the individual has a rigid and fixed obsession with ‘healthy eating’. This can include fixation on ‘pure’ foods, omitting ‘bad’ foods and an inflexible belief over the expectations and importance of healthy eating. Commonly, those with ON omit things that are ‘unnatural’, ‘processed’ or that have been processed in ways which are believed to reduce the beneficial health properties of the product.”

Symptoms include:

“an enduring worry and a pre-occupation with eating impure or unhealthy foods and what effect these would have on the body if the individual were to eat them; spending excessive time periods thinking, researching, writing or talking about food; excessive time preparing or acquiring foods which can also lead to financial difficulties due to the types of food being bought; inflexibility or intolerance to other people’s diets and beliefs about food and eating; and feelings of guilt and shame when perceived ‘unhealthy’ foods are eaten. These food-related behaviours can also lead to malnutrition due to the imbalance of the diet consumed and also difficulties with activities of daily living such as education, socialisation or work.”

While there currently isn’t a clinical consensus as to whether orthorexia is a new type of eating disorder, or whether it is a different kind of presentation of an existing disorder (such as anorexia nervosa), it is still clear that there are symptoms related to anxiety around eating certain types of foods that’s having a damaging impact on people.

That’s not to suggest that we should avoid all discussion of health foods in order to protect people whose relationship with food is influenced by a medical condition, but it does mean we have to ask ourselves whether demonising foods is a good idea when it comes to supporting a healthy relationship with food and health in our society. Encouraging restriction of certain food types can lead to increased consumption or even episodes of bingeing on those foods, and food and body shame can influence the types of food a person eats – often not in a positive way.

What can we do?

The evidence around UPFs currently isn’t settled. We see an association with outcomes of poor health and consumption of ultra-processed foods, but the cause of this relationship is a long way from being identified. Some researchers claim it’s related to particular additives like emulsifiers and gelling agents, and the good news is, we have a great mechanism for testing claims like that.

In the UK, the Food Standards Agency reviews all new research on food additives, and regulates them. All additives currently available on the market, including those in UPFs, have already been assessed based on the current evidence. The FSA says:

“All food additives must pass a robust assessment to check they are safe for people to eat. An assessment looks at the toxicological profile of a particular additive, its concentration in particular foods, the range of foods in which it is used, and how much we might be exposed to it in our overall diet. We then use that evidence to judge whether the additive is safe, in what quantity, and how it can be used in different products. When new information comes to light about the safety of a particular additive, we will reassess its safety if necessary, based on the latest scientific evidence.”

So I invite those researchers, who think food additives are the issue here, to bring their evidence and prove it. Once we’ve got the science, the FSA can and will regulate the use of those additives.

Ultimately, I think it’s important that we continue to research a wide range of different food types and how they influence our health, but the key thing is to use this research to influence how food manufacturers are regulated, and how food policy is considered.

We absolutely should not be using that research to drive sensationalised headlines, which give people yet more food to feel anxious and guilty about.