Holocaust denial – the belief that one of the most heinous human atrocities in history never actually happened – is unquestionably pseudoscientific. Any amount of Holocaust revisionism in society is a grave cause for concern, which is why it is little surprise that a report from the Economist in December 2023 garnered so much attention. “One in five young Americans thinks the Holocaust is a myth”, read the headline. “Our new poll makes alarming reading,” came the subtitle.

The finding was reported in newspapers and media outlets the world over, including The Telegraph, The Hill, and The Times of Israel. The Daily Mail covered it, on the 10th December.

One in five young Americans believes the Holocaust is a myth – while another 30% say they are unsure if the genocide ever took place, poll finds

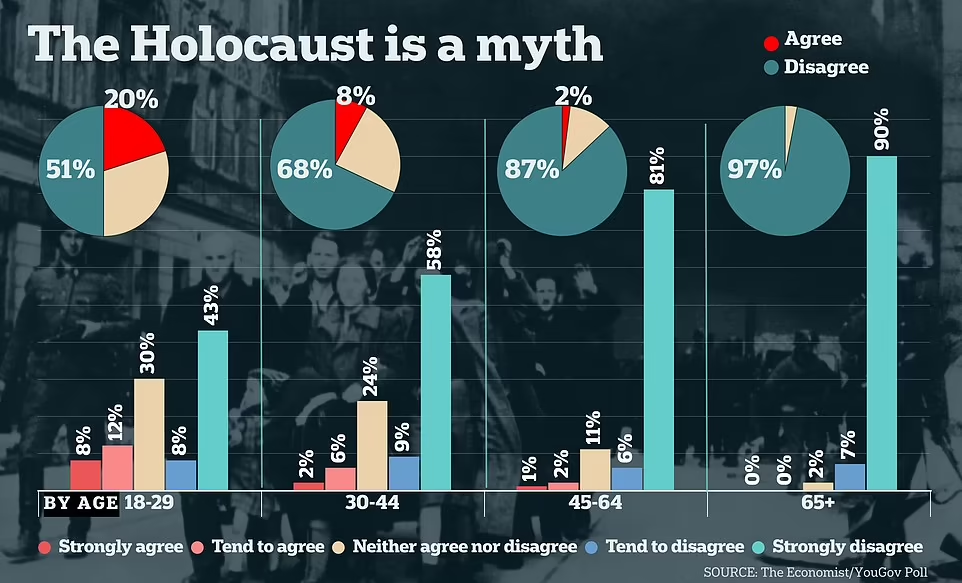

The Mail covered the story again two days later, complete with eye-catching bar charts to illustrate the clear and stark generational divide when it comes to Holocaust denial.

The report came at an incredibly heightened time, in the wake of worldwide protests against Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza – a war which began in response to the October 7th terrorist attack by Hamas, but has escalated into widespread destruction, devastation, and the killing of an estimated 37,000 civilians. None of that death, of course, is on the hands of Jewish people outside of the leadership of Israel, countless thousands of whom have marched in solidarity with the people of Gaza with a view to stopping the war.

The notion that a fifth of young people believe the Holocaust to be a myth is obviously concerning, and it’s not the only concerning finding from the Economist’s study. The same research found that 24% of people think it is not antisemitic to claim that American Jews are more loyal to Israel than the US – despite allegations of dual loyalty being a long-standing antisemitic trope.

Additionally, the report found that while 9% of people think the Holocaust was exaggerated, that number rises to 23% among those under 30, with 28% of that group also believing Jews have “too much power in America”, and 31% saying Israel has too much control over global affairs.

The Economist and YouGov

This research was part of a regular feature by the Economist, where they collaborate with research company YouGov to take the temperature of the nation. YouGov being the responsible polling company that it is, made that survey data fully available, which means it can be scrutinised… and that’s where we start to get the sense that something doesn’t add up.

While YouGov and the Economist found that 20% of under 30s said they felt the Holocaust was a myth, the same research found that Biden voters were twice as likely to believe this as Trump voters, and that Democrats were twice as likely to believe it than Republicans, which seems surprising given what we know about the current Trump iteration of the Republican party and its acceptance of conspiracy theories like Pizzagate, QAnon, the Hunter Biden Laptop, and more. It’s not impossible that a party that’s taken wholesale to its core scaremongering about George Soros somehow rejected Holocaust denial at a greater rate than the rest of the American political landscape, but it seems surprising at least.

The YouGov study was conducted between the 2nd to the 5th December, with the Economist story running two days after the poll closed. It was an online poll conducted via YouGov’s website and app, with a representative sample of panellists drawn from their opt-in panel. Anyone can be part of YouGov’s opt-in panel, they simply need to create an account online, and each day they’re given access to a range of surveys to complete. To incentivise participation, panellists are given points upon completing each survey, and once they reach 25,000 points they can cash them out for a $15 Amazon gift card. According to some reports, each survey earns a few hundred points, though it is not always clear before taking a survey how long it will take to answer, and how many points it will earn.

These are standard practices in the online polling world, but they’re also potential weaknesses. For one, a high cash-out threshold means it is likely that many participants will spend hours taking surveys only to never reach the point where they can recoup their reward. As part of my research into online polling methodology and its impact on the media (formerly homed at badpr.co.uk), I have taken part in hundreds of such online surveys, but have successfully cashed out only once.

This high threshold for reward comes with an attendant risk: users are therefore incentivised to take as many surveys as they can in order to reach the cash out level, inevitably watering down their interest and investment in giving reflective, thoughtful answers. This is not the only way in which users are incentivised to prioritise speed over accuracy.

Perverse polling incentives

The Economist’s weekly poll requires a threshold of 1,500 respondents. This is not an atypical figure – often such polls will look to survey under 2,000 people before reporting on their findings. However, typically points are rewarded to the first 1,500 respondents to complete a survey, not the first 1,500 people to open a survey. It is often the case that respondents can be halfway through completing an online poll, only to be told that the survey is now closed, as the respondent limit has been reached (it was a regular experience among the hundreds of such polls I have taken).

Practically, therefore, the micropayment structure incentivises participants to take as many surveys as they have access to, and then to answer those surveys as quickly as possible. Those who spend an hour really considering their responses and ensuring they’re accurate and reflective of their views will come away with zero points, while those who speed through with little-to-no care will get paid.

In the case of this Economist/YouGov poll, the survey was 66 questions long. That’s a lot of questions. On top of that, many of the questions were multi-part questions (real example: “How would you rate the president listed below?”, with five names, each of whom had to be answered separately). The questions about the Holocaust and antisemitism came after 107 questions had been asked, and came in the form of a 12-part question. There were 141 questions in total in this survey.

Now, bear in mind that the whole time a respondent is answering, the clock is ticking. If they pause and really consider their opinions, they could end up investing an hour into really answering this survey, only for 1,500 other people to spend five minutes clicking the first box they see; the speedsters get paid, and the thoughtful respondent gets nothing. Clearly, the incentive is to answer quickly, thinking very little about it, speed through, click click click oops you just denied the Holocaust. Notably, as best as I can tell, “The Holocaust is a myth” was the first part of this 12-part question, and “Strongly Agree” would have been the first box to check.

Maybe not everyone who admitted to being a holocaust denier were these thoughtless speedsters, but it is easy to see how it could be a real factor. Fortunately, a few errant clicks in a population of 1,500 might not have a particularly big effect, but once you break the results down by category, you might amplify the potential impact of any mis-clicks or thoughtless clicks. These results were analysed nine different ways: by gender, race, age, income bracket, voter status, 2020 presidential vote, political party, political ideology and residential category (eg Urban, Suburb, Rural). The more different ways the data gets cut, the more chance of finding an outlier result (and, in less ethical surveys, the more bites you get at getting at finding a juicy headline).

Of the 1,500 people to take part in this survey, just 206 were from the under 30 age bracket – the age group that made the headlines. 20% of those 206 people said the Holocaust was a myth. These international headlines were based on the apparent views of just 41 people. How many of those were people who were speedily clicking through to earn a small number of points, and so clicked the first box they saw, which was that they “strongly agreed” with the Holocaust being a myth? Also, given the lack of definitions in the question, how many of them were unsure what the term ‘myth’ meant (when, for example, ‘lie’ would have been unambiguous)?

In my opinion, the Economist ought to have suspected that these data were not accurate. There were warning signs elsewhere in the same survey: looking at the question “How much discrimination do the following people face in America today?”, for the age group 18-29, only 12% said Jews were not discriminated against at all. This feels an uneasy fit with 20% of that demographic being Holocaust deniers. More to the point, to the question “Do you think it is antisemitic to deny that the Holocaust happened?”, 17% said it was not antisemitic. So, 3% apparently admitted that they were being antisemitic in their Holocaust denial beliefs?

Later in the same poll, in response to questions about abortion, 44% of respondents said abortion should be illegal, or only legal when the life of the mother is in danger. That’s a notable increase on other polls, which usually has abortion opposition closer to 35%. However, when breaking that down by age, those under 30 were the group most likely to oppose abortion, at 48%. For comparison, other polls have abortion opposition in the under 30s at just 26%.

These numbers ought to have been viewed as obvious outliers, and should never have been the main subject of an article in a mainstream magazine without verification and follow-up. This should be straightforward to understand: if your sub group analysis comes up with an eye-catching result in one of more than 100 things you’ve measured, with a very small sample size, you don’t shout it from the rooftops until you replicate it in a more focused and reliable study.

To the Economist’s credit, they did eventually update their story, adding a note at the start:

Editor’s note (27th March, 2024): After this article was published, the Pew Research Centre conducted a study on this topic. It found that young respondents in opt-in online polls such as YouGov’s were far more likely to say the Holocaust was a myth than were those surveyed by other methods, and that in general, young and Hispanic participants in such polls are unusually prone to providing “bogus” answers that do not reflect their true views.

Pew’s investigation and replication

That Pew follow-up study is highly informative. Titled: “Online opt-in polls can produce misleading results, especially for young people and Hispanic adults”, it points out that when it comes to opt-in surveys, just as I’ve been arguing for more than a decade, people will click through surveys very quickly without thinking about their results, especially if there’s a micropayment incentive at the end of it.

More specifically, Pew explained:

this type of overreporting tends to be especially concentrated in estimates for adults under 30, as well as Hispanic adults. Bogus respondents may be identifying this way in order to bypass screening questions that might otherwise prevent them from receiving a reward, though the precise reasons are difficult to pin down.

Screening questions are a weakness that I’ve also been highlighting for more than a decade – when looking at the PR market research industry, I would give the example in lectures of the screening question: “Have you been on an airplane in the last six months?”. Clearly, such a survey is unlikely to be about the time you weren’t on an airplane. But, the incentives drive participants to take as many surveys as possible, in order to accumulate sufficient micropayments to cash out, so they find a way through the screening question, and in doing so pollute the end data.

Similarly, I wrote many years ago about a screening question I saw that asked “Do you have a child? And are they with you now?” Obviously this survey wasn’t asking that in order to find child-free people – it was (predictably) about children’s attitudes to playing outside, and its results made headlines across the news media, even though it was based on data that I know was unreliable. There’s also nothing stopping people registering with a second account, with a different demographic profile, because the you that’s a 25 year old Hispanic mother might have access to more surveys, and therefore have a better chance of you turning those points into cash.

By way of illustration of this principle, Pew included a question in one of their opt-in surveys in February 2022, asking people if they were licensed to operate a nuclear submarine. 12% of adults under 30 said yes to that question. If accurate, that would mean there were six million qualified nuclear submarine operators under the age of 30 in the US.

Pew also pointed to studies that highlighted this issue when it comes to other online surveys and their headline-grabbing findings, including when respondents reported having tried drinking bleach to protect them against COVID-19, or that they had a widespread and genuine belief in conspiracies like Pizzagate, or that they felt that violence was an acceptable response to political disagreements. You might have seen coverage of some or all of those findings at the time, but you probably didn’t realise they were based in flawed polling methodology and likely ‘bogus’ respondents.

So how many young adults really deny the Holocaust? In a follow-up study by Pew, specifically designed around that question, using a postal survey where it’s harder for people to lie about their identity and where they have less time pressure to answer, the results were… 3% of people. And, it turns out, that figure was the same across all age groups. That’s still not great, it still means 3 in every 100 people doubt the veracity of a historical event, but it’s not headline-worthy.

This kind of story is why I have always been so interested in market research data and opinion polling. Because while nobody really cares whether an online hookup site wants to lie about the attractiveness of Jeremy Clarkson, all of the flaws and errors and perverse incentives that lead to that story can be present in far more important stories like this one. And while it’s not that big of a deal that journalists at national titles uncritically reproduce press releases and findings from dodgy PR surveys about cleaning products and mattresses and confectionary, the pressures and failures that lead to them copy and pasting survey-based stories without ever really scrutinising them are just as present when it comes to stories where scrutiny really matters, because the implications are significant for society.

All of the failures that allow dubious data to flourish in the press are just as relevant for the stories that pass as real criticisms and descriptions of the society in which we live, where misinformation and unchecked assertions can have an impact on the real world. It’s not just about criticising marketing or media fluff pieces, it’s about having the tools to question the forces that construct a narrative, and shape our understanding of society.