In August last year, the Religious Education Curriculum Directory announced the release of a new syllabus for Catholic faith schools called ‘To Know You More Clearly’, set to be implemented in September 2023. Catholic faith schools represent roughly 10% of state-funded education and many of them have adopted this syllabus. Currently, students are in their third term of learning under this syllabus.

Between the ages of 13 and 14, students enter year nine, a pivotal stage marked by an increased curiosity about the world and increased engagement in social and political affairs. It appears that ‘To Know You More Clearly’ aims to leverage this developmental phase, intending to foster a deep understanding of Catholic beliefs among students, especially in their outlooks on social and philosophical issues.

In secondary schools throughout the UK and Wales, including non-faith-based institutions, the introduction of philosophical and ethical debates typically begins in year nine, within religious education or dedicated social education classes. The objective is to stimulate students’ engagement with ideas, broaden their moral comprehension of the self, and enrich their interactions with others and wider society. This approach is echoed in ‘To Know You More Clearly’, highlighting the importance of such discussions in shaping students’ moral compass and worldview.

When students in year nine start to examine social issues and philosophical questions, the authors of ‘To Know You More Clearly’ frequently reiterate that they should do so purely within the framework of “the nature of human beings who were made in the image of God.”

This is the aim of the module; to delve into the “mystery of imago Dei” and how it sheds light on fundamental truths about human nature. It also aims to examine the moral significance of the beliefs that “human life is sacred” and that humans are “stewards, not owners, of life”. These concepts are supported by referencing St Paul’s teachings on the dignity of the human body in Corinthians 6:12-20. This passage highlights the importance of using the body in accordance with moral principles and serving the Lord rather than engaging in “sexual immorality”. It underscores the sacredness of the human body and its connection to Christ. The conclusion to the passage reinforces the idea that human bodies are regarded as temples of the Holy Spirit, emphasising the importance of respecting and honouring God through one’s actions and treatment of the body.

In this social issues module for year nine students, the syllabus outlines week-by-week debates on different philosophical areas, presenting converging social issues within a unified discussion. One week’s topic explores “ethical issues related to the sanctity of life”, covering subjects such as abortion, euthanasia, IVF, capital punishment, genetic engineering, and eugenics. Examining this within the context of imago Dei and the connection to St Paul’s teachings on the ‘dignity’ of the human body, it’s difficult not to notice the intentional alignment and implied association between abortion and IVF with eugenics and genetic engineering. Abortion is revisited later in the syllabus with further emphasis on imago Dei and the sanctity of human life, emphasising the belief in every individual’s right to life and physical integrity from conception to death.

In my own Catholic religious education, abortion and IVF were discussed merely to fulfil a requirement, with the teaching centered on their classification as sinful acts against the body as a vessel of God. This framing of the debates surrounding the body appears to be a deliberate attempt to influence undecided young people.

In the same module, a parallel comparison of social issues emerges in the section focusing on bodily autonomy. The curriculum delves into “ethical issues related to the integrity of the human body”, such as torture, kidnapping, domestic violence, and the distinction between gender as a biological, versus gender as a social construct. Once again, the syllabus guides students’ discussions, more prominently this time, by juxtaposing torture, kidnapping, and domestic violence with the debate on gender, which includes acknowledgment of transgender identities. This implies that transgender identities or experiences of gender diversity are violations of bodily integrity akin to the heinous nature of torture.

The language concerning marriage in the curriculum exhibits a similar bias, particularly evident when discussing the “Difference between civil and sacramental marriage” and contrasting civil law with the Church’s teachings. The syllabus’ stance emphasises that marriage requires a man and a woman for it to be sacramental. This suggests that marriages recognised under civil law, including queer and gender-diverse marriages, are deemed invalid according to Church teachings. When schools adopt this stance, it implies the invalidity of individuals’ identities, potentially impacting their well-being within the institution.

The syllabus emphasises that by the unit’s conclusion, students should grasp the Church’s teaching on marriage as “a lifelong partnership between a man and a woman, freely entered into, which is ordered towards the good of the spouses and the procreation and education of children”. This passage employs language laden with significance, notably the term ‘ordered’, reinforcing the belief in marriage exclusively between a man and a woman. The use of ‘order’ implies institutional influence over married individuals, evoking traditional, divinely ordained structures and prescribed lifestyles.

It is also essential to note the shortcomings of the syllabus in presenting non-religious perspectives objectively and inclusively. The syllabus postpones introducing an atheist alternative to the Catholic worldview until key stage three. Additionally, when addressing non-religious perspectives, it claims to be “motivated ultimately by love” for individuals who do not recognise the universal scope of Christ’s salvation.

There is emphasis placed on the notion that the syllabus’ omission of non-religious perspectives would constitute a ‘missed opportunity’. The syllabus teaching atheist perspectives is seen by the authors as an “opportunity for those young people in our schools who are culturally and unthinkingly atheist” to see the Catholic way of living. There isn’t any reference to initiatives aimed at broadening students’ perspectives. Atheism is solely mentioned to confront the “ubiquitous, atheistic worldview which dominates much of our cultural life” and to ‘save’ and enlighten students who are, to them, atheist by default.

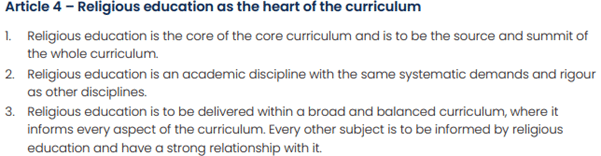

In addition to lacking comprehensive teaching on alternative beliefs, this curriculum strongly advocates for the integration of Catholic teachings throughout all subjects. It emphasises that religious education should influence every aspect of the curriculum, encouraging students to use Catholicism as a foundational framework for understanding all subjects.

The debut of this syllabus could significantly impact the cultural and political awareness of its target audience, diverting young people from introspection about their identities and decisions. Instead, it encourages adherence to societal conventions and institutions, framing personal identity, relationships, and physical attributes within the context of serving a larger purpose.