You might be forgiven for thinking that rich white men have a penchant for saying outrageous things when it comes to demography. For example, the late Prince Philip once said that if he were reincarnated, he “would like to return as a deadly virus, to contribute something to solving overpopulation.”

Not to be outdone, Elon Musk has gone to the other extreme, and frequently quips that “population collapse due to low birth rates is a much bigger risk to civilization than global warming”; in his view, it would be nice if there were trillions of humans.

Demographers have long debunked Musk’s alarmism. But even admitting that we are nowhere near population collapse, wouldn’t it indeed be nice to have trillions of humans? Most people would probably be neutral regarding this question. As per this view, assuming that our standard of living remains the same, adding people to the world does not make it better or worse.

But what if we add, as a thought experiment, babies born with terminal, painful diseases, whose lives are likely to be very short and dominated by suffering? In that case, most people would probably agree that it would be a bad idea, and therefore that the world would be worsened if those lives were added to the population. Yet shouldn’t there be symmetry in our approach to adding people? If it is bad to add some lives, wouldn’t it be good to add people with lives worth living?

Some people might refuse to accept that symmetry. In their view, if we bring to existence people with lives we collectively deem not worth living, we are causing them harm. But if we fail to bring to existence people with lives we would consider worth living, we are not causing any harm, precisely because there is no existing person that has been grieved.

This view seems reasonable, provided we assume that actions are bad only if they harm someone. But there may still be actions that are wrong, even if nobody has been harmed. If a person is not allowed to board a plane because of their race, and that plane crashes, that person would come to recognize that such an act of discrimination saved their life (and therefore they were not harmed), but the deed is still wrong. Consequently, we may not properly harm the trillions of people that we fail to bring to existence, but not bringing about their existence may still be bad.

In fact, if we reflect further, it seems that we would not be neutral about adding people with lives we collectively deem worth living. Under the assumption of neutrality, it would be the same if a couple had a child or not. Yet, we would certainly prefer that child to have a fully satisfactory life, instead of a half-satisfactory life but still worth living. If we were really neutral, either option would be the same (full satisfaction vs. half satisfaction), since adding lives worth living does not make the world a better place. But for us, the first option is clearly preferable. That implies we are not neutral about adding people. More is better; trillions of humans are a good thing.

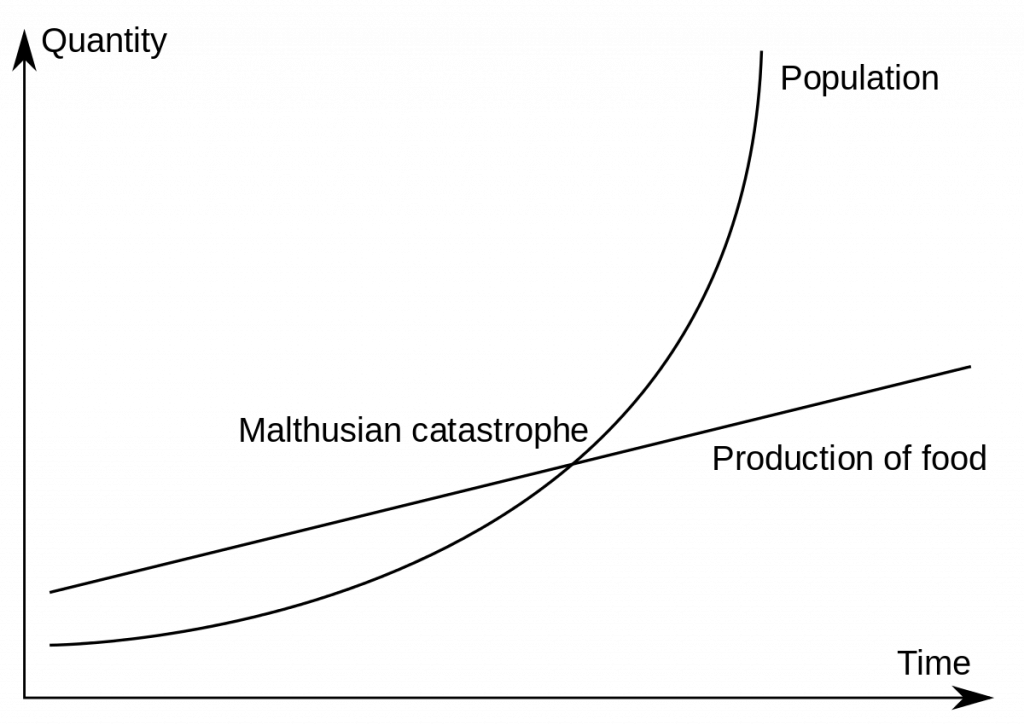

But with trillions of humans, wouldn’t life be horrible for all of us? As Malthus famously warned, overpopulation is bound to cause war, famine, pestilence and disease – presumably, this was Prince Philip’s concern. Surely if we stay on Earth – populating the galaxy would be another matter – a population of trillions would make our lives miserable, probably to the point of not worth living. But what if we maximize population size – say, tens of billions – therefore decreasing our quality of life, but not to the point of having lives not worth living? Suppose we have a humongous population size with lives barely worth living. In that case, wouldn’t more be better?

Most people would find this prospect worrisome, and indeed, many philosophers have called it ‘repugnant’. But it has a disturbing logic of its own. When it comes to happiness, it seems the total number is a better measure than the average number.

Consider this example to see why. Suppose you are a teacher, and you will take 20 students on a field trip on Thursday. On Monday, the school principal budgets £10 for each student. Your total budget is therefore £200. On Tuesday, the principal has a change of plans, and now wants to add 20 more students, and for those new students, the budget will be £5 per person; the new 20 students will not have as much fun as the original 20 students, but they will still enjoy the field trip. The total budget now will therefore be £300. Is that a good deal? Yes, it is, as the original 20 students have not been harmed, the new 20 students will be happy to go on the field trip, and the budget has increased.

The principal does not like inequality, so on Wednesday he proposes to distribute the budget evenly across all students, and he will add £50 more to the budget. The budget would therefore be £350, and each student would have £8.75. Is that a good deal? Again, yes, it is, as the situation is now more just than it was on Tuesday, and the budget is even larger. So ultimately, the plan proposed on Wednesday is better than the one proposed on Tuesday, and the plan proposed on Tuesday is better than the one proposed on Monday. Consequently, the plan proposed on Wednesday is better than the one proposed on Monday.

As compared to the plan proposed on Monday, the one proposed on Wednesday increased both the number of students going on the field trip, and the total budget. From Monday to Wednesday, the average budget per student decreased (from £10 to £8.75), but we don’t seem to care about that, to the extent that we consider the Wednesday plan better than the Monday plan. It then seems that total measures are better than average measures.

Let us now return to world population size. Is a population of 1 billion people, and happiness level 50 each, better than a population of 100 billion people and happiness level 1 each (but with lives still worth living)? The reasoning above suggests that, to the extent that total measures are preferable to average measures, 100 billion units of happiness are better than 50 billion units. If we followed average measures, then in a world with 1 billion people and happiness level 50 each, it would be better to add one person with a horrible life (to the point of being not worth living), than to add 1 billion people with happiness level 45 each, as adding that person with a horrible life would only have a negligible effect on average happiness. This is absurd, and it seemingly proves that ultimately, total measures are what counts.

Shall we therefore follow Elon Musk’s directive to have as many babies as we can? Not necessarily. The prospect of trillions of humans with lives barely worth living does seem depressing, and I, for one, refuse to give in to it. Yet, there is no easy way out of that logic. Derek Parfit – the philosopher who first considered these dilemmas – hoped for decades to find a solution to the conundrum of population size; he never succeeded.

For now, what may be most needed is an acknowledgement that demography, in and of itself, is not enough to get around this problem. Philosophical reflection must also play a part. Elon Musk may be easily refuted when it comes to factual demographic assertions, but the worldview underlying his outrageous claims must be taken seriously. Never forget that for skeptics, philosophy matters.