Acting is so riddled with superstitions that many of them have made it into common parlance – Break a leg! or, The Scottish Play, and so on. Most of the time these sayings are pretty harmless, closer to being idioms than actual beliefs, their purpose more in teaching young thespians to respect the communal space of the theatre than anything else. But unfortunately, as I discovered when I attended drama school, theatre has a more serious problem with superstition, one that runs much deeper – and it all starts in the studio.

For some context: I studied at a top British conservatoire in 2016. What became quickly apparent to me, after my first few classes, is that teaching acting is actually very difficult. And I don’t mean learning it is difficult – which of course, it is – but so is the actual act of teaching someone how to improve at the art form. Acting is an experiential skill – you get better by doing it, by practising it at a high level, much like a footballer learning to take the perfect free kick, or a fast bowler practising line and length. You’re given some good basic advice: Relax your body, speak up and don’t rush, don’t drop character until you’re out of sight of the audience, etc. But that only takes you so far.

What about the really tough stuff, like how to truthfully perform a scene in which you’re told your children have been murdered? (The Scottish Play, Act 4, Scene Three) Or when you get that dreaded stage direction – they laugh? Try that last one for yourself – genuinely try and make yourself laugh, I dare you. It’s like trying to force yourself to sneeze.

This is all without mentioning the subjectivity that comes with analysing what makes a performance good or bad which, if you ask anyone who has seen the many performances of Nicolas Cage, isn’t so obviously clear-cut.

Because of this difficulty in explaining the craft, at least in my experience, many acting teachers employ a kind of pseudoscience couched in artistic academese. Acting, many seem to claim, is about getting to the correct creative state, about inhabiting the soul of another, about finding the correct energy (the last one sounds more like advice you’d give to a Jedi rather than a serious student). It is a continuation of what seems to be a lot of discourse around art and artists – that creativity doesn’t come from the mind, but from the soul.

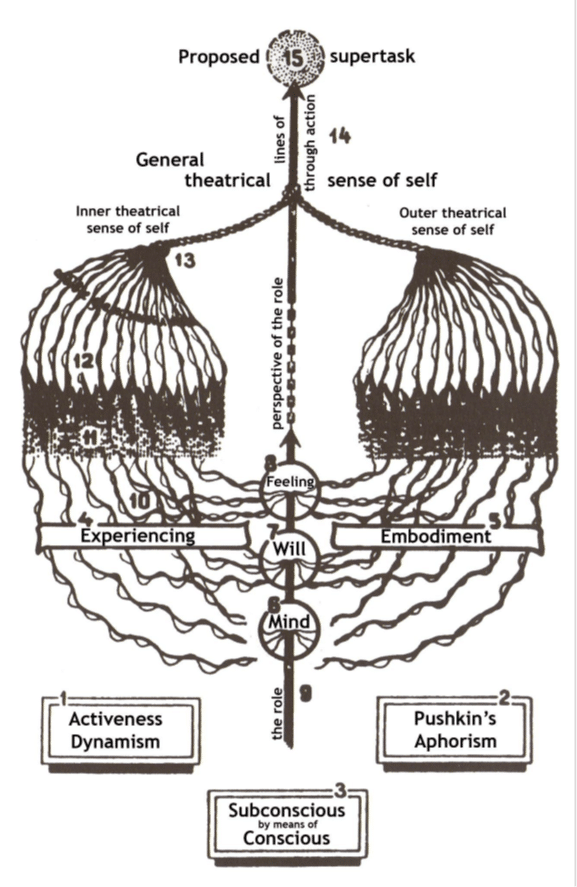

Different acting gurus have come up with their own methods in an attempt to codify this approach into something seemingly respectable, but most of their efforts are equally numinous, or even borderline quackery. Consider the following diagram that purports to explain the ‘method’ of the grandfather of acting technique, Konstantin Stanislavski:

Make sense to you? No, it doesn’t to me either, and I’ve studied it!

Or what about Sandford Meisner, who devised an exercise where actors were given a line, and told not to say it until something compelled them to say it, wherein Meisner pinched the back of the male student and put his hand under the blouse of a female student – does that sound constructive?

I’ve had teachers try and heal students’ disabilities with Reiki, talk about the ‘invisible rays of intention’ that actors might psychically receive, and have spent hours being told how to commune with the energy of inanimate objects to learn how to puppet them ‘truthfully’. This spurious pedagogy isn’t even well hidden – look at some of the courses of study as advertised on certain drama schools’ websites: ‘Body Centring Experiential Anatomy and Pilates,’ or promising to ‘Remove blocks or inhibitions to emotional and imaginative spontaneity’ or teaching you how to ‘…cultivate psychophysical connectivity’. I’d recommend looking at the websites of some of these schools for yourself, and you’ll see what I mean.

But why is this a problem? Is this anything more than just well-meaning hocus-pocus that, even if misguided, might help young actors get better? I think there is a concern here. Drama schools, as anyone who has attended one can attest, are also high-pressure, both in their student culture and in their teaching methods. The industry is oversaturated, and the competition to be the best, the most talented, the most beautiful, is fierce. Young actors will do anything to prove that they’re committed to the artform, to impress their teachers, including buying into a lot of this nonsense methodology. And then, at least in my experience, they come up against such spurious pseudoscience and find that it is impossible to actually implement, to act upon.

When they fail, their teachers can often be quite brutal. I once had a tutor pour a bottle of water over a classmate’s head when they thought she wasn’t focussing enough, or another who screamed obscenities when the young man forgot his lines, or in a whole-year feedback session tell them that they had no future in the industry because they didn’t understand the school’s methods. So young actors think their failures are a problem of character – their own character, as if their souls were defective because they can’t find the correct energy, whatever that means.

This continues into the industry, too, and, coupled with a general failure of pastoral care, is reflected in the data around performers’ mental health. A scoping review conducted by Dr Lucie Clements for the performers’ union Equity found that depression is twice as likely in performers than in the general population. The review also notes that, where six percent of the general public is thought to experience anxiety in any given week, in comparison, 24% of dancers, 32% of opera singers and 52% of acting students experience weekly anxiety.

The Equity review goes on to state that: ‘…negative relationships with others in positions of power in the workplace, who were demanding, unsupportive or authoritarian also created huge stress in the industry’ and that ‘…many papers have argued that education providers rarely provide sufficient support and acting students are predominantly underprepared in education for how to look after their psychological well-being once in the industry.’

These young actors surely won’t be helped with more yoga, more energy, or a more slavish subscription to a series of these ‘New Agey’ artistic methods, many of which were first formulated before the discovery of penicillin. What these young people require is evidence-based mental healthcare.

As for support in developing the craft of acting itself, I think perhaps there’s a more rational approach, one that doesn’t require energies or intentions. Acting is simple enough – it’s an illusion that happens in the mind of the audience when they see a clever combination of believable narrative and interpretable human behaviour, and not the soul of the actor, whatever that is. All a young performer needs to do is speak up, relax, and practise. If they’ve got talent, it’ll come naturally. I don’t think it’s more complicated than that.

And perhaps, if their teachers spent a little less time obsessed with energies and a bit more time on this craft and student care, our drama schools might both justify the huge debts that these young people leave with, and become kinder and more reasonable places, too.