On the 2nd of November, 2021, author and journalist Laura Dodsworth retweeted a very strange video. Created by the Covid-sceptic organisation PANDA, it depicts a young woman walking slowly through a misty natural landscape. Scored with ominous music, juxtaposed with distant city noise echoing in the background, a hypnotic voiceover begins:

It is everywhere. From the news programming, to the media headlines, to the political speeches, to the education initiatives. It’s on the posters on the trains. It’s in the articles that you read. It’s in the text messages you are sent. You are right to feel that something is not right. You are right to feel that you are being manipulated… Governments and institutions globally have engaged behavioural teams with the prime purpose of altering your decisions and behaviours. It may feel easier to ignore what’s going on, but the only way to reduce its influence and break the chains is to think consciously about what and why. Listen to your intuition. It is telling you something is amiss. You are right.

Attempts to portray oneself as a lonely, crusading truth-teller in a dystopian world is certainly not alien to those claiming to challenge ‘mainstream narratives’ around the COVID-19 pandemic. And while such overtures would likely make even David Brent blush, it is easy to see why a video like this could be compelling to casual viewers. With undertones verging on romantic, it has an eerie, almost trance-like quality to it. It is both mesmerising and disturbing. Half guided meditation, half terrifying wake up call. The dream-like text combined with sparse yet serene natural landmarks makes the message of the video clear. This is about blocking out the corrupting noise of institutional power and trusting your gut. In order to ‘break the chains’ of government influence we must ‘listen to intuition’. We are ‘right to feel that something is not right’, because we are ‘being manipulated’. If you weren’t feeling afraid before watching this video, you certainly are now.

Anyone with even a passing familiarity of Covid-contrarianism will know that seeding gut-level suspicion at the expense of reality is a huge part of the movement’s modus operandi. This is why simple factual corrections seldom work on those sympathetic to these kinds of arguments. Their position is not a factual one – it is an experiential, emotional one rooted often in fear. While Covid-sceptics may outwardly profess sceptical values and claim that they are engaging simply in the business of rationality – ‘think consciously about the what and the why’ – their enterprise relies entirely on urging their followers to float along in an obscuring fog of confirmation bias. Untethered by inconvenient realities, unmoored by matters of fact. You must keep walking through the fog – you are right. Behind the facade of reason, nurturing spooky hunches is the entire sorry game.

In her retweet, Dodsworth captioned the video with one word:

Interesting.

Setting aside my own opinion that the word ‘interesting’ is at its best when not interchangeable with ‘hunch-affirming’, we should be extremely grateful to Dodsworth for sharing the video. Had she not, we might never have been exposed to one of the most exquisite, unintentional satires of conspiratorial thinking ever to exist. It is a withering deconstruction, verging on avant garde. In my opinion, by retweeting it, whether Dodsworth realises it or not, she perfectly and succinctly summed up the totality of her own written work about the pandemic.

Her Sunday Times best-selling book – ‘A State of Fear: How the U.K. Government Weaponized Fear During the COVID-19 Pandemic’ – is pitched as a sceptical examination of mainstream pandemic narratives. It purports to ask ethical questions about the U.K. government’s response to managing the spread of COVID-19. However, upon closer inspection, I believe it is full of the very same groundless appeals to fear that she spends 281 pages criticising. As well as referencing all of the usual unreliable sources cited by her far less palatable ideological bedfellows, her book is light on facts, heavy on hunches, and rife with misleading analysis.

As Dodsworth herself discloses at the outset:

This is a book about fear, not about data

I couldn’t agree more.

‘A State Of Fear’

Readers of this magazine may not be too familiar with Laura Dodsworth, owing to the fact that her work seems to have attracted almost no attention from critical media, and seemingly none at all from the scientific-Skeptic movement. This may be partly due to our own appetite for examining the most brazen, colourful strains of nonsense – the pandemic being no exception. While the more eye-catching claims surely deserve our attention, we mustn’t let this come at the expense of critiquing misinformation that comes across as more moderate or reasonable. After all, palatable nonsense can do just as much harm as obvious nonsense – arguably even more so under the veneer of respectability.

From a distance, Dodsworth herself does not come across as an extreme or overtly controversial voice. She does not doubt that vaccines provide essential protection. Her articles have been published by relatively mainstream, albeit conservative, outlets. To the uninitiated, she comes across as rather sensible. She is only asking questions, after all. And, on first glance, the central thesis to her book seems as though it could even be an intriguing one. Dodsworth contends that:

… the behavioural scientists advising the U.K. government recommended that we needed to be frightened. The Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behaviour (SPI-B) said in their report… “a substantial number of people still do not feel personally threatened… the perceived level of threat needs to be increased among those who are complacent, using hard-hitting emotional messaging”. In essence, the government was advised to frighten the British public to encourage adherence to the emergency lockdown regulations.

Dodsworth continues:

This book explores why the government used fear, the specific tactics, the people behind them, and the impacts of fear, including stories from people who were undone by fear during the epidemic. Most of all, this book asks you to think about the ethics of using fear to manage people.

Specifically, her consternation centres around the Behavioural Insights Team – informally known as the ‘Nudge Unit’ – and how they leveraged fear during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to ‘frighten’ British citizens into complying with restrictions and mandates. Founded under David Cameron’s 2010 coalition government, the ‘social purpose company’s’ notional remit is to influence public attitudes and decision making via behavioural economics and psychology so as to enhance civilian compliance with government policies. Notable campaigns in the past have included initiatives that purport to help reduce behaviours such as smoking, physical inactivity or texting while driving. Similar campaigns predate the existence of official ‘Nudge Units’ by quite some time. While Dodsworth acknowledges the value of such ‘laudable aims’, she writes scathingly about the organisation’s recent activities, it’s apparent lack of transparency, and the theoretical framework on which it is based:

The person who coined the term ‘nudge’, Cass Sunstein, said, ‘By knowing how people think, we can make it easier for them to choose what is best for them, their families and society.’ Isn’t it great that there are people who know what is best for you? Rest assured, there are many behavioural scientists and their advocates embedded and advising within the U.K. government, nudging you towards what is best for you… Making no bones about it, nudge is clever people in government making sure the not-so-clever people do what they want.

Dodsworth claims to have reached out to David Halpern, the founder of the organisation, for an interview. She received an evasive response, in which Halpern insisted he was an ‘admirer’ of her work, but declined to comment on any questions pertinent to Dodsworth’s area of concern. She claims to have spoken to:

… an anonymous scientific advisor deeply embedded in Whitehall. They told me that flattery is a very common tactic used by the government when people ask difficult questions. This echoed my suspicious gut feeling.

Suspicious gut feelings, as we will see, are in abundant supply in this book.

Hyperbole aside, and to be fair to Dodsworth, the question of whether it is ever acceptable for a government to use fear to influence the behaviour of its citizens does strike me as having the potential to be interesting – in the truest sense of the word. Is the use of fear by a government to alter the behaviour of its citizens, notionally for their own good, ever morally justifiable? Are there ever any political uses of fear that are both warranted and desirable? If so, when? And to what extent? Should the scale or severity of the perceived threat factor into the equation? Should the use of fear be proportional to that threat? If so, how might we best quantify, measure and calibrate each of those expressions?

This feels like fertile ground for a fascinating discussion – one which political theorists and undergraduates are already having, it should be said. Sadly, none of their work is referenced or engaged with in Dodsworth’s book – though she quotes at great length voices that happen to agree with her position already.

Dodsworth’s opening gambit might perhaps call to mind the government sponsored road safety campaigns in recent decades, which have seen the production of many horrifying TV adverts – famous for their shocking, graphic depictions of road accidents – warning of the dangers of careless driving. Such campaigns are often associated with reductions in driving deaths, according to government surveys, and might serve as examples of when political utilisation of fear is both warranted, desirable and effective. Does Dodsworth discern a difference between fear leveraged to reduce motor vehicle deaths and fear leveraged to reduce deaths from a deadly virus? In what ways do those examples differ? Why do those differences matter?

The potential for a capacious and rewarding debate on liberty, free will, truth and ‘the greater good’ is plainly present in Dodsworth’s premise. In all honesty, I was quite looking forward to one unfolding as I began reading her book. Unfortunately, it is a potential that she spends almost 300 pages squandering by way of flimsy sources, hyperbolic language, and selective evidence. Bluntly, it is simply not possible to have a productive, honest discussion of the question ‘did the government’s use of fear go too far?’ when such a question is essentially immediately followed with the unfounded suggestion that Covid wasn’t actually that bad.

After writing in her introduction that ‘this is a book about fear, not about data’, she continues:

Nevertheless, some additional data will be required to help you contextualise the threat of the disease with the policies for managing it, and you will find that in Appendix 1. A few facts and figures assist with framing the scale and dangers of Covid, and subsequently assessing whether escalating our fear was appropriate or not.

Indeed, Appendix 1 does appear to contain infection fatality estimates from a few different sources, including the CDC and Imperial College London. However, in the interest of fully ‘framing the scale and dangers of Covid’, it should be noted that ‘dying’ is only one potential outcome. There exists a whole host of other long-term effects and life-altering health outcomes that a SARS-CoV-2 infection can bring, of which vaccines can reduce the incidence. Neglecting to mention these isn’t exactly painting a full picture of the threat, and anyone doing so might well be considered a ‘Covid minimiser’.

This, though, isn’t even the most glaring red flag of Appendix 1. For alongside infection fatality data from public health agencies – which itself is not entirely clear-cut – comes a reference to an ill-famed report from Professor John P.A. Ioannidis.

In the last few years, John Ioannidis has become notorious for his sudden and unexpected descent into anti-consensus views about the pandemic. Despite a position as a respected scientist and scholar, Ioannidis has made a number of false claims and untrue predictions about the pandemic. He co-authored a seroprevalence study which purported to find that, due to supposedly higher infection rates, SARS-CoV-2 infections were milder than initially thought. The study suffered from serious design flaws, and was roundly criticised. Ioannidis once claimed that many lives were lost early in the pandemic due to improperly administered intubations. This too was unsupported by good evidence. At the very beginning of the pandemic, Ioannidis wrote a highly circulated piece in STAT, in which he suggested – all while being careful enough to maintain plausible deniability – that pandemic estimates may be greatly exaggerated due to a dearth of sufficient data. A rebuttal was published a day later, with others pointing out the piece’s dubious mathematics.

However, these incidents pale in comparison to the controversial report Dodsworth references in Appendix 1 for ‘A State Of Fear’. Even by Covid-sceptic standards, it is quite exceptional. The paper contains so many problems that it is difficult to list them all. One commenter on the preprint attempts to outline a handful of them below:

![Text reads:

"Atomsk's Sanakan

Some flaws in this study that render it's IFR estimate unreliable:

1) He uses many studies that over-estimate the number of people that were infected [and thus under-estimate IFR], since these studies were not meant to be representative of the general population loannidis applies them to. He doesn't even follow PRISMA guidelines for assessing studies for risk of bias in a study's research design. "Bias" here does not refer to the motivations of the study's authors, but instead that the design of their study would likely cause their results to not be representative of the general population.

2) He exploited collinearity by sampling the same region multiple times, in a way that skews his results towards a lower IFR. He conveniently tends to avoid sampling an area multiple times when that area has a higher IFR.

3) He adjusts IFR downwards for reasons not supported by the analysis he cites for that adjustment.

4) He takes at face-value areas that likely under-estimate COVID-19 deaths, such as Iran, causing him to under-estimate IFR further.

5) He uses inconsistent reasoning to evade government studies that show higher IFR, even though governments are doing much of the testing needed to determine IFR. That includes loannidis ignoring large studies from Italy and Portugal that are more representative of the general population they sampled.

6) His IFR from a study in Brazil contradicts the study's own IFR, and his explanation for that makes no sense. This conveniently allows him to cut the study's IFR by about a 1/3.

7) His use of blood donor studies does not make sense, even if one sets aside the fact that blood donor studies would over-estimate population-wide seroprevalence. For example, he uses a Danish blood donor study that leaves out deaths from people 70 and older, to claim an IFR of 0.27% for adults. When those researchers performed a subsequent study in which they included people 70 and older, they got an IFR for adults that's 3 times larger than loannidis claims [0.81% vs. 0.27%).

And so on."](https://www.skeptic.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/atomsks-sanakan.png)

Somehow, this paper has become one of the most influential and frequently referenced sources in anti-vax circles, despite the fact that virtually none of the 61 studies Ioannidis cites sufficiently support his infection fatality rate (IFR) estimate. In many cases, he calculates a vastly underestimated IFR as a result of citing studies that use non-representative sampling to overestimate seroprevalence. Essentially, if we say that many more people have COVID-19 than actually do, the percentage of people dying from it looks smaller. It is a very effective way of minimising the ostensible threat of the disease. Many have pointed out the catalogue of flaws the report contains. Yet, in her book, Dodsworth cites it uncritically and without caveat. She even goes as far as to praise Ioannidis elsewhere as being a ‘voice of expert reason right at the beginning’ of the pandemic.

If an author demonstrates this kind of apparent indifference towards quality of sources and evidentiary standards, how can we be expected to trust them? How can they be expected to build an analysis that eventually reaches insight? If this report is intended to constitute the basis for Dodsworth’s supposed ‘framing’ of the ‘scale and dangers of Covid’, how can we expect her evaluations to be calibrated meaningfully to the real world?

Dodsworth’s unfortunate taste in experts only gets stranger. The first chapter of ‘A State Of Fear’ is entitled ‘Fright Night’, in reference to Boris Johnson’s 2020 televised address to the nation urging citizens to stay home. Dodsworth contends that this ‘doomsday speech’ constituted the first major dose of fear that the government administered to the British public in the pandemic – ‘imprinting’ it on our minds using ‘very specific wartime language’. She believes ‘that’s when it began’, although ‘the priming had started weeks earlier’. She writes:

I froze. Appalled by the words… But as I watched Boris Johnson’s speech to the nation, as he told us that we ‘must’ stay home, I also started observing his body language. Why was he clenching his fists so hard? Why the staccato speech? Something seemed ‘off’ and that triggered alarm bells… I was sure that the prime minister’s language was intended to alarm me, and that in itself worried me.

Dodsworth writes that ‘at a basic level that was hard to pinpoint, it didn’t feel genuine’, that Johnson’s performance suggested that ‘he did not believe in the essence of his words’, and that ‘his words set the tone for the three weeks to follow’. The notion that a prime minister, let alone one like Boris Johnson, might engage in duplicitous statesmanship shouldn’t be a radical or inconceivable idea to most people. However, as part of an attempt to scrutinise Johnson’s direct-to-camera message further, Dodsworth writes that she enlisted the council of ‘two experts’ for their analysis. One of whom is a licensed practitioner of Neuro-linguistic Programming, whom Dodsworth gainfully tasks with the job of ‘decoding Johnson’s body language’.

Neil Shah, founder of International Wellbeing Insights, is claimed to be an expert in ‘how to read non-verbal communication’. Dodsworth asked him to watch the YouTube video of Johnson’s speech and to give her a ‘blow by blow’ analysis of his ‘body language’. Dodsworth writes:

He [Shah] told me he would be interpreting a blend of signals because 55% of our communication is through body language, 38% is volume and tone and only 7% is the actual words we use.

Shah’s assessment includes the following:

Twenty-six seconds in and you can see the tension in his fingers. He is clenching so hard his knuckles turn white… The way he is jabbing his fists at us shows tension… There doesn’t seem to be congruence between his words and his body language. It suggests he is not speaking from the heart and doesn’t believe what he is saying.

To be clear, Neuro-linguistic programming is pseudoscience. Body language is an inexact science at best, and full of unsubstantiated myths at worst. Studies have failed to find a link between non-verbal cues and deception over and over and over again. The 7/38/55 percentage rule is largely a myth, with even its originator warning against its common usage today.

This, then, might seem like quite a peculiar way to begin a book dedicated notionally to thinking sceptically and rationally about government narratives around the pandemic. However, it starts to make a lot more sense once we understand what I would argue the book’s actual goals are, and how they differ from its stated goals. This book, in my opinion, is not in the reality business per se – it’s in the just keep walking through the fog, you are right business.

Just as Dodsworth contends that the prime minister’s message ‘set the tone for the three weeks that followed’, this opening chapter sets the tone for the rest of her book. In the name of uncovering truth, Dodsworth begins ‘A State Of Fear’ by asking a non-specialist from a discredited field to give a professional opinion, via a pseudoscientific practice, in order to sow gut-level distrust. Had Dodsworth applied even one fifth of the scrutiny to her so-called ‘expert’ as she does to Johnson’s speech, she might have realised fairly quickly that this was not a reliable analysis worth quoting. Especially not if she cared about being taken seriously. Moreover, the idea that Johnson may not have believed what he was saying can be true without it having any implications about the real world threat of COVID-19, or the real-world efficacy of public health interventions. Such a finding does nothing to support such conclusions in and of itself.

Indeed, as I move through each chapter, I can say wholeheartedly that ‘A State Of Fear’ is succeeding admirably in fomenting a hunch within me personally, though perhaps not the hunch originally intended. My suspicion about the low standards of evidence harboured by the author is only deepened as Dodsworth makes a plethora of misleading claims about face masks, lockdowns and death counts.

Dodsworth asserts that face masks were implemented due to the ‘signal’ of ‘social conformity’ they promote, and not because of any evidence of efficacy. She writes:

The behavioural psychologists love masks. They absolutely love them… Behavioural scientists pushed for masks because they create a ‘signal’, when in fact not a single Randomised controlled trial can demonstrate the value of mask wearing outside clinical settings.

Dodsworth argues that masks do not work, and that there exists ‘no proof’ for their efficacy. This is not true. Their ability to reduce transmission has been demonstrated over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over again. Dodsworth cites the infamous Danmask study as evidence of researchers failing to find an effect, despite that study being one of many to have been disputed substantively for years.

The vast preponderance of evidence suggests that face masks can be a useful, yet imperfect public health tool during a pandemic. Some masks work better than others, especially when used in conjunction with other safety measures such as social distancing and proper ventilation. Just because protection is incomplete does not mean it is useless. Additionally, as many have pointed out, physical testing alone is deemed sufficient for a myriad of other public health tools, such as seat belts, motorcycle helmets, parachutes, life-jackets, and condoms. Nobody argues that these do not work due to a lack of RCT research.

In attempting to repudiate lockdowns as an effective measure for reducing transmission, Dodsworth makes a familiar argument concerning Sweden’s pandemic response:

To highlight one example, Sweden is often cited as a counter-factual [sic] to the U.K’s policies because it did not impose strict lockdown measures throughout the year… According to CEBM, Sweden only had a 1.5% increase in age-adjusted mortality. England and Wales, with the strictest lockdown in the developed world, saw a 10.5% increase in age-adjusted mortality.

As it happens, Sweden did ban public events of more than 8 people, and closed secondary schools more than once, both of which constitute ‘locking down’, according to voices on Dodsworth’s side of the aisle. Even Sweden’s state epidemiologist, who championed the country’s approach, insists that they ‘did close down enormously’, with streets remaining empty for much of 2020.

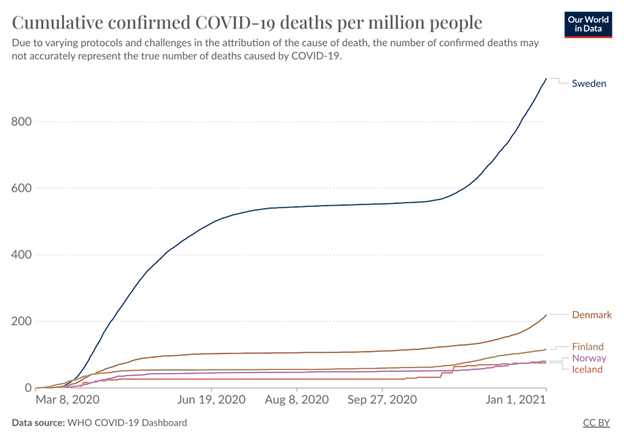

However, comparing Sweden and the U.K. in this way is inappropriate due to their vastly different geographical sizes and populations, both of which could help explain their varied outcomes. Sweden is a much larger country with much fewer people than the U.K. This means that the virus would have had to work slightly harder to make its way through the population. It would be far more analytically apposite to compare Sweden’s response to other Nordic countries with similar sizes, populations and response time-frames. Compared to countries like Finland, Iceland, Norway and Denmark, Sweden fared disastrously:

The conclusions Dodsworth arrives at with regard to lockdowns are only possible as a result of the inappropriate statistical comparisons she makes, which unfortunately misleadingly skew the analysis in her favour.

Elsewhere in the book, Dodsworth argues that the U.K. ‘lockdown itself caused a horrifying number of excess deaths’, despite very good evidence demonstrating that this isn’t quite the case. Bold claims about lockdowns causing excess deaths are common in Covid-sceptic circles, despite very little evidence to support them. Countries like New Zealand and Taiwan, which locked down but had little to no virus to contend with, had very little excess mortality. While nobody argues that lockdowns are harmless, the real story is much more complicated than the one Dodsworth presents.

Dodsworth quotes a SAGE report as predicting over 100,000 ‘non-covid deaths caused by lockdown and other impacts’, while neglecting to mention the very same report also estimated around 4,100 fewer non-Covid deaths as a result of ‘better air quality, lower prevalence of other infectious diseases, and reduced road injuries.’ In reality, many of the possible negative outcomes posited by the report, such as lower life-expectancy brought about by the recession, are a result of the government doing too little to contain the virus and locking down too late.

At most, we can say that the long-term impacts of lockdown will take quite some time to assess fully. What we cannot say is that we know lockdown contributed to a sharp increase in excess mortality. The best available evidence currently says otherwise.

In one of the book’s more reasonable passages, Dodsworth mentions that some non-Covid excess deaths may have been ‘due to delays in treatment, or a reluctance to seek treatment’. This is certainly true. Issues within the NHS, including a shortage of both staff and beds for patients, contributed terribly to the early months of the pandemic. Crucially, though, the reasons for this are due in large part to decades of chronic underinvestment in health services. Given that Dodsworth claims to be concerned about the negative impacts of lockdown on our collective health, it seems odd that she would go on to make common cause with those who campaign most fervently for the privatisation of the very health service that exists to help us.

In a chapter entitled ‘Counting The Dead’, Dodsworth casts aspersions on the true death toll of COVID-19. She begins the chapter inauspiciously by writing:

We humans keep dying. We always have. We always will.

She continues:

At a time when it is crucial to understand why people are dying we have less clarity due to the changes in registration and recording… The difficulty now is that although death tolls are confidently asserted, the relaxation of the death registration in order to cope with the worst case scenario means we don’t really know how many people have died of Covid.

Dodsworth is correct that we may never know how many people have died from COVID-19. However, almost every reason for this points to the true death toll being undercounted all over the world, not overcounted.

For example, Dodsworth writes that ‘there is uncertainty about some care home ‘Covid deaths’ actually being due to Covid.’ She quotes an anonymous ‘scientific advisor’ as saying:

We have no idea how many people died because of this disease, or poor clinical decision-making in the early days, or neglect in care homes.

While Dodsworth implies here that some Covid deaths in care homes may be attributable to ‘neglect’ rather than the disease itself – a point which would be impossible to disprove – it is far more significant that the near-complete absence of testing in care homes during the first wave means that care home COVID-19 deaths were almost certainly undercounted, which could add up to 10,000 more deaths to the UK’s COVID-19 death toll. This issue was raised by the ONS as early as June, who noted additionally that undiagnosed Covid in the elderly could sometimes present with symptoms that can look like dementia:

This could fit with recent clinical observations, where atypical hypoxia has been observed in some COVID-19 patients. In someone with advanced dementia and Alzheimer disease, the symptoms of COVID-19 might be difficult to distinguish from their underlying illness, especially with the possibility of communication difficulties.

Dodsworth, however, does not link to any research here to support her claim about Covid deaths in care homes. Instead, she quotes an anonymous care home worker in the north of England who offers a handful of individual anecdotes of ‘cases where Covid had been inaccurately put on the death certificate as the cause of death or an underlying cause of death.’ Dodsworth relays one such anecdote:

One resident, well into her 80’s, tested positive for Covid at the end of March 2020, when she had mild symptoms. She recovered, but went on to die in August. A covering doctor who had never met the resident, or seen the body, insisted that Covid must have been a cause of death.

The anonymous care home worker is then quoted as saying:

She actually died of old age, quite peacefully and contentedly.

Dodsworth then asks the reader:

How many times did this happen in care homes across the country? There is an abundance of anecdotal stories on social media from families or care home workers who say that Covid has been incorrectly put as a cause of death on the certificate.

Even if unverified anecdotes from social media were an appropriate source for such a claim, Dodsworth cites none here. She also interviews an anonymous coroner who shares a ‘similar story’. She writes:

They [the coroner] were called by a doctor they knew personally, asking for advice about ‘an old boy who’d had multiple kidney infections and died just eight hours later in the hospital.’ Against her better judgement, the doctor agreed to do a Covid swab, although she knew he’d died because of his kidneys. It was positive and she had to put Covid on the death certificate.

Dodsworth writes that she asked the coroner if they thought that this would turn out to be ‘a common tale’. The coroner responded:

We have no idea.

On the basis of this, Dodsworth concludes:

The Covid death total is probably inflated, because Covid has been used too liberally on death certificates… As all of my interviewees said, we have no idea how often it has happened, and now we never will. If, in the most horrible of circumstances, a resident was neglected or suffered some grave misfortune, it could be passed off as Covid.

It is important to notice what Dodsworth is doing here, as I believe it is a tactic that propels almost every argument in her book. She begins by highlighting existing uncertainty around COVID-19 death tolls, which is a genuine phenomenon – though not necessarily for the reasons Dodsworth claims. Then, she quotes from anonymous sources who relay a handful of worrying, unverified anecdotes about Covid being falsely attributed as a cause of death. Finally, she concludes that we simply have no idea how often this has happened across the country…

Based on threadbare sources and unverified anonymous testimony, Dodsworth seeds the idea of ‘inflated Covid deaths tolls’ being a potentially widespread problem across the U.K.. For all her talk of the government ‘planting ideas’ in the minds of its citizens, she has planted this idea in the minds of her readers. In perhaps one of the best examples of this, she writes:

The coroner told me an apocryphal story about a family holding a dead body up to a window so the doctor had ‘seen’ the body. He wasn’t entirely sure whether the story was a joke or not.

Referring to the anecdote as ‘apocryphal’ is ingenious. It allows Dodsworth notionally to dispute the story while still leveraging it for emotional effect, insulating herself against any criticism of sharing false, sensationalised stories for the purposes of horrifying her readers. She never technically said that she believed such a story to be true, after all. Mentioning that the coroner ‘wasn’t entirely sure if the story was a joke or not’ carries the furtive implication that even if it isn’t true, it’s the kind of thing that could be. Dismissing a horrific image after you’ve described it in detail still leaves the reader with a horrific image in their mind. ‘Imprinted’, as Dodsworth herself might say.

Reading ‘A State Of Fear’ almost feels like reading a whodunnit. A sinister inkling is born at the outset, encouraged as the story goes on, and matures eventually into full-blown conspiratorial dread. She refers to masking as a ‘cult’, and – in a passage that, for me, put to bed any notion of her position as a moderate voice in this discussion – draws parallels between the U.K.’s pandemic response and Nazi Germany:

The Coronavirus Act and Public Health Act were terrifyingly draconian (see chapter 15, ‘Tyranny’) and one could potentially draw parallels with Nazi legislation.

Her penchant for selective scrutiny pervades almost every page, writing favourably about some of the worst peddlers of misinformation in the pandemic. She writes uncritically about the Great Barrington Declaration, despite their proposals being foundationally flawed. She refers to Dr Clare Craig as someone who was unduly criticised for ‘asking controversial questions’, ignoring her patent record of Covid casuistry. She quotes Carl Heneghan at length, a British GP who once claimed that there was ‘no sign of a second wave’ in the middle of the second wave. In her acknowledgements, she thanks Zoe Haracombe – a HART member who once wrote that she wanted ‘ADE [Antibody-Dependent Enhancement] kicking in hard and fast soon!’ to harm people who chose to get vaccinated, thereby validating her vaccine scaremongering. For a voice as sensible as Dodsworth, these certainly are intriguing ideological bedfellows.

Her subsequent scholarly ventures raises interesting questions about the consistency of her stated beliefs too. Despite dedicating an entire book, many television appearances and a litany of articles to condemning the psychological targeting of British citizens for political purposes, she is currently promoting a new book co-written with Patrick Fagan, the former ‘lead psychologist’ of Cambridge Analytica. It was during his time there, according to InsideBE, that Fagan:

… learned the power and methods of data science mixed with behavioural science, to send the right people the right nudge at the right time… using big data to infer audience psychology and send targeted behavioural interventions, with a particular focus on personalised nudges…

His new book with Dodsworth is entitled ‘Free Your Mind: the new world of manipulation and how to resist it’. It is billed as ‘the must-read expert guide in how to identify techniques to influence you and how to resist them’. For what it’s worth, Fagan rejects the notion that the Cambridge Analytica scandal is about ‘ethics’, because ‘everyone is doing it’.

Readers might notice how antithetical this seems to Dodsworth’s cause – in my opinion, it’s rather like co-writing a book about the dangers of house fires with a known arsonist. However, interestingly, a 2017 study found some experimental evidence for a phenomenon known as ‘partisan nudge bias’, in which ‘individuals evaluate the acceptability of a policy nudge by instead assessing how they feel about the associated policy objective or policy sponsor’. Essentially, people are less likely to criticise ‘nudges’ that they happen to agree with, and more likely to criticise ‘nudges’ they personally dislike. So it is quite possible that Dodsworth may be applying some selective indignation here. After all, such a phenomenon appears to be supported by scientific research, which I would argue is more than can be said for many of the arguments in her book.

‘A State Of Fear’, funnily enough, appears keen to frighten you. It warns you that you are being ‘nudged’, while relentlessly nudging you from cover to cover. It advances a score of misleading claims – about masks, lockdowns, death counts, and government infractions on liberty comparable to Nazi Germany. In the absence of comprehensive evidence or reliable sources, it relies heavily on inflaming suspicions and stoking gut-level unease. As a result, Dodsworth’s response to any factual criticism could quite easily be ‘well, even if this particular thing isn’t quite true, you can’t deny that something doesn’t feel right here…‘ It is a one-size-fits-all stratagem that will likely continue to serve Dodsworth in whatever future endeavours she pursues.

One thing should be painfully clear by now. Dodsworth’s Covid corpus engages in the very same baseless appeals to emotion she so vehemently decries. This foreboding feeling is the constitutional currency of her entire book – animating every argument, steering every chapter. In my opinion, there is nothing ‘sensible’ to be found here, only more fog. Rather like the eerie, trance-like video that she retweeted years ago, Dodsworth’s argument depends on persuading you to suspect that your worst, most sinister, most ill-founded hunches are correct. Do not fall for it.

I do not believe that Laura Dodsworth is campaigning against a state of fear. In my view, she is working tirelessly to perpetuate one.