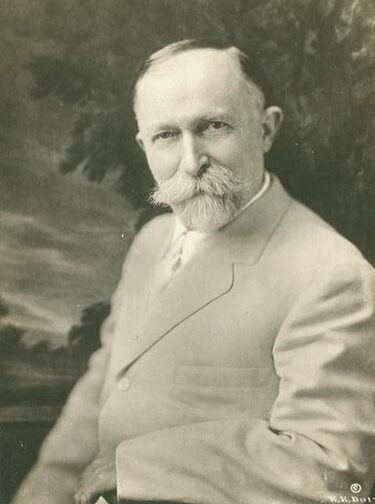

John Harvey Kellogg was born in 1852 and grew up in Battle Creek, USA. He was the son of devoted Seventh-Day Adventists, a faith that he later adopted to the full. The young Kellogg soon developed a keen interest in medicine and health and, in 1872, he began to study at the ‘Hygieo-Therapeutic College’, a private medical school focusing on water cures and ‘hygienic therapy’. Just five months later, Kellogg enrolled at the University of Michigan Medical School and then at the Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York, where he graduated in 1875. Kellogg’s devotion to natural cures was dominant early on; already as a medical student, he became the Editor of ‘Health Reformer’, a journal that later changed its name to ‘Good Health’.

Fresh from medical school, in 1876, Kellogg became the medical director of a 20-bed reform institution run by the Adventists. By the turn of the century, he had renamed it the ‘Battle Creek Sanatorium’ and enlarged its capacity to accommodate 1,200 patients.

Soon, Kellogg had become a household name in the USA, and his patients included many prominent industrialists and politicians. To Feed them, Kellogg and his family had invented not just his now famous corn flakes but also a variety of other foods, including peanut butter, artificial milk made from soybeans, and a range of imitation meats.

Synthesising his Adventist beliefs with his medical assumptions, Kellogg created his idea of “biologic living”, i.e. the idea that a healthy diet, combined with exercise, and recreation was required in order to maintain a healthy body, mind, and soul. In his view, biologic living would protect health effectively and even render vaccinations unnecessary.

Kellogg’s business was booming, and profits initially went to the ‘Race Betterment Foundation’, which Kellogg had created in 1914 for the promotion of eugenics. Kellogg wanted to arrange human reproduction to increase the occurrence of heritable characteristics that he regarded as desirable (Fee & Brown, 2002).The foundation organised three conferences; a fourth meeting was planned but was interrupted by World War II. Due to the news about the Nazi Germany’s Holocaust, the appetite for further gatherings subsided.

In the sanatorium, everyone had to adhere to a strict focus on diet and life style which were meant to cure a person of practically all ills, leading to a kind of purity of the soul. Meat and spicy foods as well as alcohol were thought to overexcite the mind and lead to sinful behaviour.

Kellogg’s range of treatments on offer included:

- Vegetarian diet

- ‘Light bath’, baths under the sun or artificial light lasting hours or even days

- X-ray therapy

- Regular exercise

- Various forms of electrotherapy

- Vibrational therapy

- Electrotherapy

- Massage therapy

- Breathing techniques

- Colonic irrigation delivered by specially designed machines that could deliver 14 litters of water followed by a pint of yogurt, half of which was to be eaten, while the other half would be delivered via a second enema

- Water cures of various types

Kellogg was also obsessed with sexual abstinence, including various measures to avoid masturbation. For boys, Kellogg recommended circumcision without anaesthetic, arguing that the trauma would curb any sexual desires. If circumcision did not suffice, he advised sewing the foreskin shut to prevent erections. For girls, he applied carbolic acid to the clitoris as ‘an excellent means of allaying the abnormal excitement.’

Much of what Kellogg did and advocated had an undertone of salvation. The language of changing the body and communing with the divine combined into the practice of natural healing through God’s creation. Kellogg embraced the notion that God could touch humanity through nature. ‘Biologic living’ was centred around purity, not merely of the soul but racial purity too. Meat and alcohol were not just bad, they were considered ‘race poisons’.

Kellogg warned of the peril of ‘race suicide’, a term that summed up the fear of white Americans, namely that their racial purity would be eroded and disappear into ‘inferior races’. He also helped implement a law whereby genetically ‘inferior’ humans such as people with epilepsy or people with learning disabilities could be sterilised. Michigan’s forced sterilisation law, in which Kellogg had a hand, was only repealed in 1974.

Kellogg died on December 14, 1943, in Battle Creek where he is also buried. In his will, he left his entire estate to the above-mentioned Race Betterment Foundation.

And what about Kellogg’s claim to fame, the corn flakes? Are they as marvellous and healthy as Kellogg and his followers made them out to be? The short answer is no. They are boring and full of sugar and starch. Crucially, there are many better options for a healthy breakfast. Try eating more whole grains, fruits, oats, yoghurt, and make sure your diet is balanced.

References:

- Fee, E., & Brown, T. M. (2002). John Harvey Kellogg, MD: health reformer and antismoking crusader. American journal of public health, 92(6), 935.