Humanity has for a long time been fascinated by the question: “Is there language out there?” It is one of the most intriguing questions, along with “Is there life out there?”.

Learning the animal languages is an eternal dream of mankind, reflected in beloved fairy tales and fiction — C.S. Lewis’s Narnia is inhabited by speaking animals, and Harry Potter speaks parseltongue, the serpent language. However, most animals prove to have no complicated communicative system that could resemble human language. Our searches for language in animals have been limited to simple signals, only some of which may be assigned with a kind of meanings (as the screams for “eagle”, “leopard”, and “snake” in vervet monkeys).

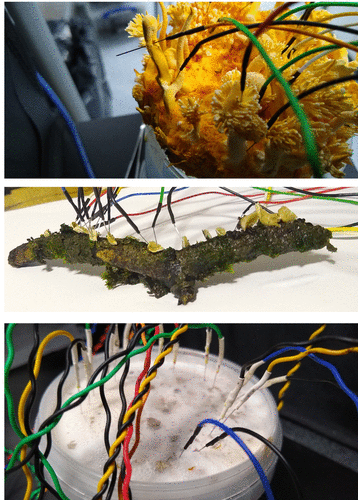

But recently, two similar results on very dissimilar organisms were published. Both species have been mathematically proven to communicate with shorter signal sequences (“words”) that can be combined into longer sequences (“sentences”). The most intriguing thing is that these signals have different physical nature: if in the case of chimpanzees, they are good old-fashioned vocalisations, whereas fungi build “words” and “sentences” from the electrical bursts of cell membrane potential. These bursts are highly similar to action potentials in human neurons which are the basis of electrical signalling in the nervous system.

While press-releases and “popular science” outlets reported on the findings with eye-catching headlines, could it actually be true that we have revealed language in chimpanzees (and in fungi)? I think that at least, we cannot say for sure.

A similar finding springs to mind immediately: the “language” of dolphins. Their communication is excessively characterised and very complicated. It is often regarded as a language in science fiction: the “dolphin language” is a central element of the plot in The Dolphins of Pern by Anne McCaffrey and in Dolphin Island by Arthur C. Clarke. In Visitor from the Future by Kir Bulychev, studying ‘dolphin language’ is even a vacation task for school children. This reflects the enduring interest in dolphin communication since the 1960’s.

However, for such a long time nobody could prove exactly that this communication system is a language. Some mathematical attempts to do it face a lot of criticism from the scientific community. For more than a half hundred years of extensive research we have known that bottlenose dolphins use personal signatures similar to human names — but this is the only deciphered part of their “conversations”. This is rather insufficient — for example, individually specific calls have recently been reported in elephants, but one will need a very luxuriant imagination to suspect them of having a language. This is the reason why today’s zoologists keep avoiding the term “language” regarding dolphins and speak about their “communication system” instead.

This problem of distinguishing between communication systems (a more common entity) and language (a specific kind of communication system) is crucial also in the case of the “fungi language” and “chimpanzee language”. The main challenge is the absence of a definitive set of criteria which can be checked mathematically. Anastasia Bonch-Osmolovskaya, PhD in Linguistics, Researcher in DH CLOUD Community, comments:

In both articles, the word “language” is used in the sense of “system of signs”. Semiotic scientists of the 1970s actually liked to describe “languages” of bees, dolphins etc. from this perspective. Within the same meaning, one can discuss programming languages and even air traffic control language which is the set of clear univocal signals, too. To what extent these “languages” exhibit properties of a natural language — for example, ambivalence, redundancy, generativity, different language functions beyond the information transmission function — it is highly questionable. Many philosophical articles have been written about these properties of human language, and one cannot just up and find Top 10 properties of the human language anywhere.

The most known attempt to enumerate properties of human language was made by American linguist Charles F. Hockett. He listed multiple “design features of language”. Seven most principal features mentioned in modern textbooks are: (1) mode of communication, (2) discreteness, (3) interchangeability, (4) cultural transmission, (5) arbitrariness, (6) displacement, and (7) productivity. Now, a half century after Hockett’s works, some researchers do not agree with him, but cannot offer any definitive set instead. As a result, we don’t have any criteria to check computationally.

This leads to a situation where, in a best case scenario, authors check the statistical characteristics of a studied communicative system against the set of criteria they prefer or even postulate themselves (as in the case of “chimpanzee language”). There is no prize for guessing that this way can “discover” language anywhere, but the linguistic relevance of such discovery is highly questionable. Maybe this is the reason why “language” vanished from the peer-reviewed article title while present in bioRxiv preprint — authors tried to make emphasis on communication, not language. The same can’t be said for some media outlets.

In the worst-case scenario, no list of “design features” is used. In the paper on “fungal language”, the statistics of fungal communication are compared only to the statistics of the English (and sometimes Russian) language. Using English as a single reference has already led Noam Chomsky to his “Universal Grammar” which fails to explain features of Pirahã language and even ancient languages like Akkadian or Sumerian (for more details read the book Through the Language Glass by Guy Deutscher). This kind of reference does not allow us to draw any conclusions about languages “in general”.

Does this mean that the efforts of computer scientist Andrew Adamatsky (author of the paper on “fungal language” known for his impressive previous experiments with problem-solving slime moulds) and the research group of “chimpanzee language” are futile? I don’t think so. Adamatsky’s paper provides invaluable insights into the action potential of fungi. We knew that this kind of electrical signalling occurs not only in neurons but also in nerveless animals, and even plants. Now we have a detailed description of electrical signalling in fungi. They are really like us — not in terms of language, but in terms of action potentials.

The research on chimpanzee communication seems even more promising to some linguists. Svetlana Burlak, linguist, professor of Russian Academy of Sciences, studies the origin of language problem for a long time and has summarised her studies in the book “Origin of language: Facts, research, hypotheses”. She is convinced that chimpanzees and other apes do possess some evolutionary prerequisites for acquiring language, such as the ability to use gestures for communication, and these prerequisites were the basis on which human language developed. She explains:

This was to be expected that chimpanzees’ communication would reveal properties similar to those of human language. That sounds great that they were found. Now, we have one more building block in the understanding that human language didn’t come from thin air but was created from something that was already present.

Thus, the both articles provide valuable evolutionary insights, and the only problem is a dubious status of describing their findings as “languages”. This problem arises only from the absence of strict testable definitions of language. Astrobiologists searching for life on other planets know that one of the most difficult questions is “What is life?”. Maybe searching for “language out there” will raise a similar question: “What is language?”.