Our wildlife comprises more than two million known animal species and more than 100 “unknown” ones, which are suspected of existing by mystery enthusiasts and a lot of people across the world. Some of them enjoy such strength of belief as to make even Santa Claus envious (if he were real, of course). They are cryptids — creatures, not recognised by science, but widely believed to exist. A pseudoscience aimed at their search is called cryptozoology.

For the most part, this “science” is based on anecdotal eyewitness accounts rather than controlled observation and experiments. They are typically a weak argument, but there is one more thing that takes cryptozoology beyond science, but makes it difficult to disprove it directly. This thing is unfalsifiability. No hypothesis about the existence of a cryptid has any pre-defined boundaries beyond which it would be considered refuted. For example, the hypothesis about the existence of the Higgs boson has been falsifiable ever since it was predicted by Peter Higgs: if it was not identified in controlled conditions of a collider experiment, it would become clear that this prediction is erroneous. But it is almost impossible to directly refute a statement about the existence of a creature, unknown to “official” science — we would need to travel all around the Earth, including to all mountains and lakes, to be sure that Nessie or Bigfoot do not really exist.

This is not a problem for science — it is for a long time established that unfalsifiable hypotheses should not be taken seriously. That said, the Multiverse hypothesis is also unfalsifiable — yet we are happy to discuss it. Maybe we have additional arguments in the case of cryptids, which, although don’t disprove their existence directly, indicate that they are nothing more than a myth? I think so.

Any myths, including urban myths, take on a life of their own, and sometimes, they contain traces of psychological, social and cultural processes which are characteristic of a cultural entity, not for a real being. These traces are most easy to find in the most popular cryptid myths, since we have more data for analysis in this case.

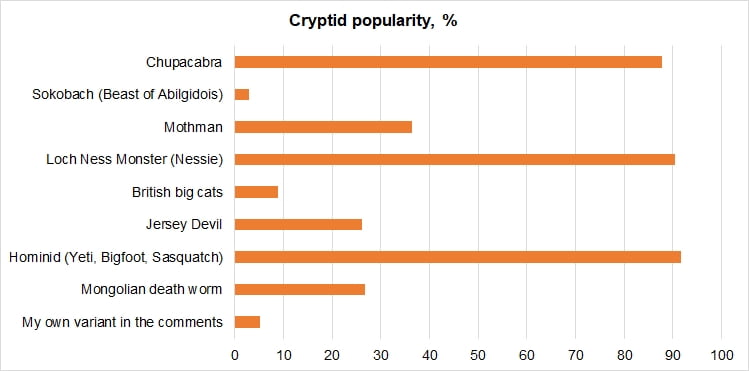

Shortly before the festival “Scientists Against Myths” in Moscow, Russia, where I was going to speak about cryptozoological myths, the organisers and I started a poll in the organisers’ group in the Russian social network “Vkontakte”. It was aimed to estimate the in-media popularity of different cryptids, and the only question was “Which cryptids have you heard about?” Of the eight listed cryptids (including one confabulated by us for a joke), only three were clear leaders, with popularity rates of 90% or more. They were the Loch Ness Monster (Nessie), the hominid “snowman” (Yeti, Bigfoot or Sasquatch), and the Chupacabra. As our audience includes primarily urban people using the Internet and acquainted with world cultural events, we concluded that our sample was quite representative. In different cultures across the Earth a lot of people are expected to believe in aquatic monsters (Nessie, Issie etc.), relict hominids, and chupacabras. And these myths have some interesting traits.

The first group of the most popular monsters — aquatic monsters, led by the world-famous Nessie — now have one phenotype across all cultures and counties. If you compare the statues of a Loch Ness Monster Nessie and a Japanese lake monster Kussie, you will not find many differences — both monsters are depicted like nice plesiosaurs. This cross-cultural similarity could lead to a hypothesis that the Earth is inhabited by surviving plesiosaurs — if we knew the phenotype of these monsters was always the same. But it was not the case.

In 2019, paleontologist Darren Naish and ecological statistician Charles Paxton undertook data science research involving historical records of witness sightings of aquatic monsters. They found that at the beginning of 19th century, these monsters were described primarily like snake-like, without a massive body or long neck. They acquired these “saurian” features in the mid-19th century, when plesiosaurs and other prehistoric sea reptiles were made known to the wider public. The Biologist features this study indicating how sea cryptids “evolved’ over a century, under the influence of a cultural event (plesiosaurs in the museums). It could not have been biological evolution, on this timescale. Thus, this is cultural evolution, indicating that aquatic cryptids are just a cultural entity, a myth, which can readily transform in our minds.

Chupacabras can rival lake cryptids in this regard — they evolved over just a decade. National Geographic tells the story of their evolution, from an alien-like creature to a canine-like animal, since 1995. The first surge of accounts about chupacabras coincided with the release of film Species in Puerto Rico, and the first chupacabras were similar to Sil, the main antagonist of the film. Once the film left the cinemas, chupacabras became more familiar and similar to diseased coyotes. This morphological switch indicates that the chupacabra is one more monster of our minds, and it lives only there.

This criterion which I call “cultural evolution” seems promising to disprove different myths about cryptids and even beyond — for example, myths about aliens and many other urban legends. And I hope the readers of The Skeptic will take it on board and find it useful in the fight against pseudoscience.

But data science methods offer one more interesting criterion — association with a known animal possibly mistaken for a cryptid. Floe Foxon, a data analyst from Pinney Associates, searches for such associations. One of his first preprints on this topic shows the statistical association between the number of Bigfoot sightings, and two population densities — the people population density and the American black bear population density. It could be one more evidence that at least some cases of Bigfoot encounters are just sightings of an American black bear ambulation on its rear legs.

It is worth saying that this association is relatively weak, and even if it were strong, we should interpret any correlation with some extent of caution. “I can find studies where the number of films with Nicholas Cage for a year correlated with the number of people who sank in swimming pools. It is real correlation without any manipulation, but this indicates nothing in the terms whether the films with Nicholas Cage cause fatal swimming pool accidents or not”, our opponent at the festival Alexander Panchin, Russian bioinformatician and science communicator, warns.

However, these were only the first attempts to use data science to prove cryptozoologists wrong, and I am sure these attempts will go on. The recent article of Floe Foxon in The Skeptic indicates that cryptid hunting is becoming science-based — but for now, we are searching for monsters in our imagination, not in the lakes or mountains.