It isn’t uncommon for news of celebrity deaths to break on Twitter, but it was still slightly surprising to see, on Monday morning, a touching and heartfelt black-and-white tribute to the Italian chef and restaurateur Gino D’Acampo.

“Parting is always difficult”, Twitter user @_malloriehoward wrote, “yet we take comfort knowing that Gino lived a fruitful and noteworthy life, leaving an enduring legacy of love, gentleness, and compassion”. The tweet included a photo of D’Acampo, in which he seemingly mourned his own passing, along with a preview of an article on theguardian.com, titled “Gino: A Remarkable Journey and Cherished Memories”.

The tweet had twenty retweets, seventy-nine likes, and over 113,000 views. It was also, curiously enough, a promoted tweet – meaning that @_malloriehoward had paid for their mourning of a beloved celebrity chef to appear in the timelines of more than a hundred thousand strangers. And, at an average cost of around $1.35 per click, reply or retweet, they may have paid as much as $135 for the privilege.

The idea of someone paying to promote a tweet that mourned the death of celebrity chef Gino D’Acampo seemed deeply weird to me – but not, I imagine, as weird as it would have seemed to the very-much-still-alive celebrity chef Gino D’Acampo.

How had Mallorie and the Guardian got this celebrity death announcement so far wrong? I opened the article to find out, though rather than being greeted with a heartfelt recollection of Gino’s “cherished memories”, instead I found a piece by the Guardian’s tech editor Alex Hern, about a recent appearance D’Acampo made on The Graham Norton Show, in which he accidentally let slip something that caused the Bank of England to call the BBC and demand the broadcast be pulled immediately. What’s more, the Bank of England, so incensed by an off-hand remark by the affable Italian, had apparently taken the unprecedented step of launching legal action against D’Acampo.

Now, it’s not uncommon for the amiable atmosphere, genial host, and liberal alcohol policy of Norton’s late night chat show to loosen celebrity lips to the point where they say something they shouldn’t have, but it is rare that those revelations result in legal threats from the Bank of England – especially, one assumes, threats against a recently-departed Neapolitan cook.

At this point, the reader ought to be smelling a number of rats. The Graham Norton show is not actually broadcast live… it also hasn’t been on air since March. The Bank of England is not currently trying to sue Gino D’Acampo. This isn’t even a real article from Alex Hern, or the Guardian; no such article appears on the Guardian website, and the links on this page don’t go anywhere – not even the curiously-Canadian selection of popular articles in the sidebar. This site has been designed to mimic the Guardian’s design closely enough to fool the casual observer, but it doesn’t survive any degree of scrutiny. The website address isn’t theguardian.com at all; it lives at the address – and it’s really hard not read some significance in this – musknews.sbs.

It might not be immediately obvious what could be gained from setting up a facsimile of the Guardian’s site in order to make up stories about a particularly charismatic celebrity cook, but a read of the purported transcript of the supposed conversation makes it clear:

[Not] Graham Norton: “You want to say that there is a way you can earn money and it works for everyone? Sounds unbelievable…”

[Not] Gino D’Acampo: “If you do not believe me I will prove you are wrong. Just give me £250 and with this platform Immediate Connect I will make a million in just 12-15 weeks!”

[Not] Graham Norton: “Oh, I have heard that there is a program that uses artificial intelligence to trade cryptocurrencies. Now everyone who watches us knows what it is called”.

For the avoidance of doubt, this isn’t the typical tone for the frothy late-night banter of The Graham Norton Show. It wouldn’t even seem natural on the Martin Lewis Money Show.

[Not] Gino D’Acampo: “I am ready to pay £20,000 right now if you cut this off. I did not want to say it. Just cut it off the air”.

[Not] Graham Norton: “Just a reminder, we are on LIVE. All our viewers have heard that you are getting rich on the Immediate Connect platform. You already spilled it out. Tell us, ordinary Britons, how we can earn money the same way as you”.

Again, The Graham Norton show is not broadcast live. Also, Norton probably wouldn’t describe himself as an “ordinary Briton”, given that he is Irish.

It’s fair to say, this exchange never happened, and D’Acampo didn’t really take Norton’s phone and use it to start making investments, live on air… nor did Norton spend 20 minutes making trades, before marvelling at the £47 profit he’d made. Nor did the following exchange take place:

[Not] Gino D’Acampo: “I just signed you up for Immediate Connect on your phone. This platform is a 100% perfect solution for those who want to get rich quickly… I do not only recommend it. I insist that every Briton should use this platform. Then, you will forget once and for all that you need to work”.

[Not] Graham Norton: “Sounds really good and legit. However, how much can you really earn on this?”

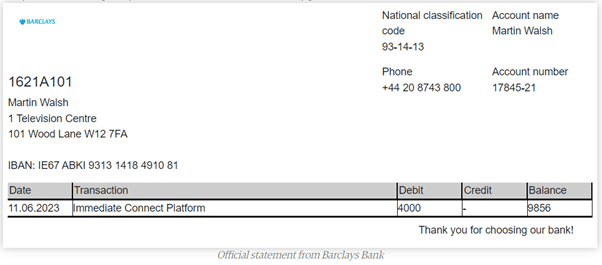

The rest of the faked exchange imagines D’Acampo schooling Norton on how to use the cryptocurrency trading platform, Immediate Connect, before the Bank of England calls up the show to demand the broadcast cease immediately, lest too many viewers rush over to Immediate Connect (using the referral link provided by Gino D’Acampo / the scammer who made this fake website) and get rich quick. The fake article even includes the seven-day-diary of Martin Walsh, “News editor” of The Graham Norton Show, as he turns £4,000 into £9,856 using the crypto exchange. As proof, it includes a shot of an “official statement from Barclays Bank”:

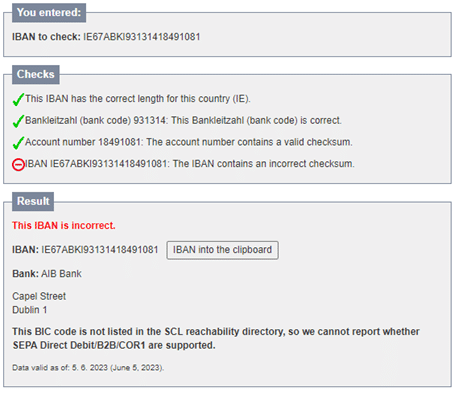

The statement is dated 24 hours before the fake article appeared in the fake Guardian (fake Alex Hern works fast!), and even includes an IBAN number… an invalid one, at that, for a Dublin-based bank that isn’t Barclays:

Crypto trading scam

This article is very likely an example of the scam end of affiliate marketing – a scam I’ve written about previously, in relation to the adverts that are algorithmically inserted into the websites of national news titles (including the Guardian). In this case, the scammer is attempting to trade off the credibility of The Guardian and the popularity of Gino D’Acampo, in order to persuade users to try cryptocurrency investments. The person who created this fake site and fake story may be part of the investment platform, or they may merely get a referral fee for every customer they send to the platform.

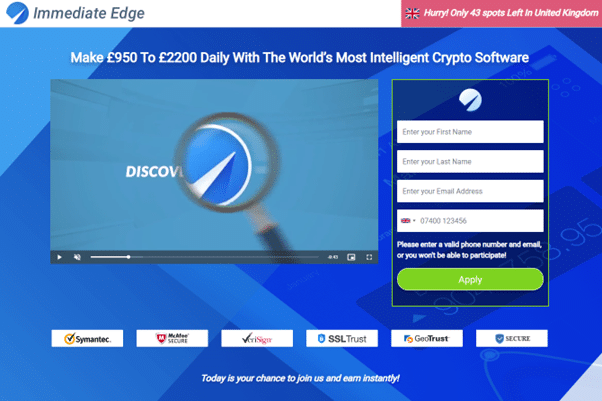

While in the article the fake D’Acampo raves about a platform called “Immediate Connect”, the referral link provided actually took me to a different website, called “Immediate Edge”, housed on the domain “gratefuloffers.org”.

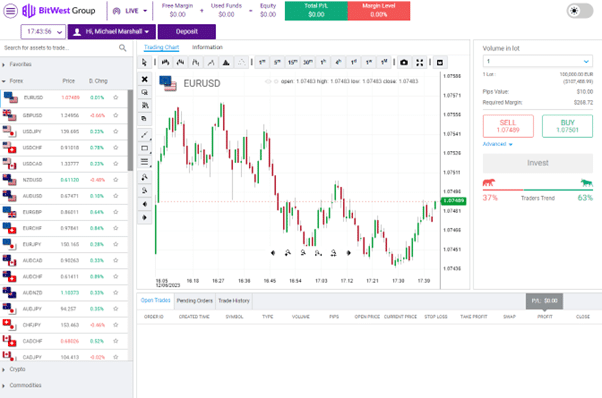

Entering contact details here takes the user through to yet another site, the actual trading platform, which is currently called BitWest Group:

It is a warren of redirects and referrals, designed to confuse the user and to put as much distance between the start and end of the process. User confusion could arguably be essential to the business model: two minutes after I entered my phone number in the BitWest site, I received a call from “Thomas”, who was working in BitWest’s London office, who told me he was my Senior Account Manager, and that once I completed my registration on the phone with him, I’d get a phone call from my “professional financial advisor with ten-plus years in the business”. Completing the registration involved moving at least £210 into my account, right then, within minutes of completing the inquiry form.

Interested to know more, I asked “Thomas” for the address of the London office where he was currently calling from. After a slightly long pause, he told me he could give me the postcode: E1W 1AW. “Is that in Farringdon?” I asked him. “Yes, that’s right”, he told me. It isn’t. After sixteen minutes of me asking questions about how BitWest works and what they would do with my money – questions “Thomas” never actually answered – he told me he was fed up, that he was sick of my “sneaky” questions, that I am not a serious person and that he deals with annoying calls like mine all day. Perhaps “Thomas” ought to look for another job.

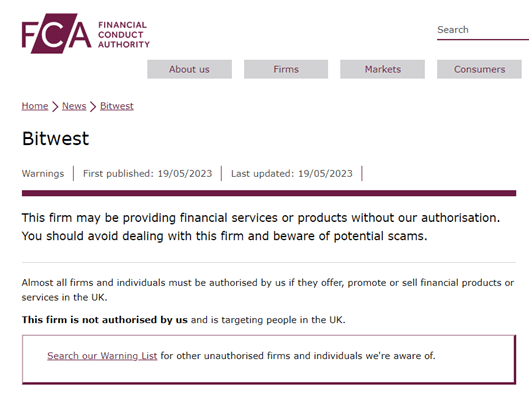

At one point “Thomas” asked me: “Oh my god Michael who is going to risk their whole reputation for your two hundred and ten British pounds?” I don’t know which reputation he was referring to – that of Immediate Connect, Immediate Edge, or BitWest. Or, I guess, of Gino D’Acampo. One thing I do know is that the reputation of BitWest is not great – in May, the Financial Conduct Auhority issued a warning to potential investors that it may be a scam

This firm may be providing financial services or products without our authorisation. You should avoid dealing with this firm and beware of potential scams.

“Thomas” wasn’t the only member of the BitWest team to call me – an hour later, I received a call from “Hayley”, who told me that she was Polish, living in the UK, and making large sums of money using the platform. I asked her why BitWest were advertising via lies about celebrity deaths, pushed via promoted tweets from unofficial Twitter profiles.

“Anything is OK when it comes to promotion,” she told me. “But it wasn’t a lie, it was on television. It was disconfirmed, but at the period of time when we launched that advertisement, it was on TV [that D’Acampo had died]. Afterwards, we found out that it was not what had really happened”. This story obviously does not make sense: I could find no TV references to the death of Gino D’Acampo, but even if it were true, at any time the company could have pulled the promoted tweets from their (variously fake or stolen) Twitter accounts.

I also asked “Hayley” why she thought the FCA so explicitly warned users against investing with her company. “The FCA says it may be a potential scam,” she told me, “Not that it definitely is a scam”. She went on to claim that BitWest did not need to be FCA regulated, as it was not giving financial advice (this is not true). She also told me the FCA warning was just proof that the government-run FCA doesn’t like it when people take control of their own finances, and so they try to punish companies that allow people to make so much money outside of the system.

I was unconvinced by the claim that BitWest was the innocent victim of a government conspiracy, nor that they were standing up to the mafia-like protection-racket demands of the FCA – particularly because BitWest’s modus operandi so perfectly resembles that of the Milton Group, which was the subject of a BBC World Service documentary in April called The billion-dollar scam.

The BBC found that the Milton Group also operated via a network of other business names, and while I don’t know whether Immediate Connect, Immediate Edge or BitWest are part of that same network, I did put that question to the “Grace” who called me two days later. Though “Grace” seemed confused as to who she worked for, introducing herself as a representative of “Streetwise”.

I asked her whether Streetwise and BitWest were part of the Milton Group set of companies. “Erm, yeah, it should be,” she told me. “So, you are part of the Milton Group, is that correct? Is it owned by the Milton Group?” I asked her. “No, it’s not”, she said. It remains unclear whether BitWest is part of the Milton Group, or if its practices merely resemble those of the Milton Group, or whether they’re genuinely the crypto-trading miracle they claim to be. But “Grace” was unwilling to be drawn on the subject – a minute later, she hung up on me. In all, within 48 hours of filling in the Immediate Edge contact form, BitWest (or whoever they may be) had called me thirteen times.

A promoted tweet problem

While the FCA has warned users not to deal with BitWest lest they be taken in by a scam, Twitter’s role as a recruiter of potential victims cannot be overstated. This all stemmed from a promoted tweet, which was seen by at least 113,000 people. That tweet came from an account that was paying Twitter $8 per month for access to the ad platform, and likely in excess of $100 for this particular ad. That money almost certainly comes from the profits of the scam, and without Twitter’s ability to reach hundreds of thousands of users, the scam would be far less likely to turn a profit. These adverts were accepted by Twitter, despite being obvious scams.

It’s not even the only promoted tweet associated with this scam: I was directed to two other promoted tweets, each from Twitter Blue accounts, each posting a seeming tribute to the departed Gino D’Acampo, alongside a link to the fake Guardian article. One had been viewed by over 260,000 people, another by over 278,000. Obviously, some of the users in each of those numbers may overlap, but clearly Twitter has promoted this scam to a huge number of its users, and it’s likely at least some of those users have handed money over to BitWest.

What’s more, this isn’t even a scam that’s unique to Gino D’Acampo and the Guardian. In May, 248,000 Twitter users were served a promoted tweet eulogizing Gordon Ramsay, which pivoted to a fake article about crypto trading. Elsewhere, Twitter accepted money to promote Wayne Rooney’s apparent death to over 156,000 users, in another ad for a crypto scam.

In some of these cases, the promoted tweet was later removed, and in some cases the associated account was suspended.

In researching this story, I was actually contacted by Aaron Rodericks, head of Threat Disruption at Twitter, who thanked me for flagging this scam promoted tweet. Soon after, the tweet and the account it came from had been removed by the platform. However, this approach to advert regulation is far too little and way too late – this scam had been promoted by Twitter to more than a hundred thousand users. By the time any action at all was taken, the scam has been run, and some people will have bought into it. When the scammers want to find a fresh set of victims, they know that Twitter will – seemingly without knowing or caring – help them facilitate the next scam, and the next after that.

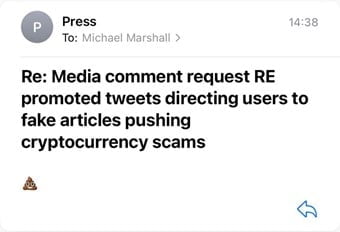

I emailed my concerns to Twitter directly, and asked them how these profiles came to be able to promote a crypto scam into the timelines of hundreds of thousands of people, what checks Twitter carry out on potential adverts to avoid directing users to scams and exploitative products, and what steps Twitter will take to ensure they’re not facilitating the exploitation of their users.

I got an immediate (auto) response from Twitter: a poop emoji. Which may well be the perfect illustration of how much Twitter cares about their profiting from the promotion of scams.