What if I told you there was a monument to slavery and white supremacy in the heart of an English city? That’s just what you’ll find if you visit Rumford Place, an unassuming street off Liverpool’s Old Hall Street. Each building is named after a place or person from the former Confederate States of America, and there are a couple of plaques commemorating fallen soldiers and a warship.

The site is linked to Liverpool’s long and shameful associated with the transatlantic slave trade. From around 1700, cargo ships laden with trade goods would leave Liverpool’s docks, bound for West Africa. They would trade the goods for enslaved people, who would endure terrible conditions as they were taken to the New World. After selling their “goods” in lands such as Barbados, Jamaica or the thirteen colonies that would go on to become the USA, the traders would then load up with stock to sell back in Europe. Sugar, cotton and tobacco all commanded high prices. Each triangular journey was hugely profitable, leading to the growth of the port of Liverpool in the 18th century.

In North America, enslaved people were forced to work on farms and plantations. Following the American War of Independence, slavery was picked apart little by little in the North, whereas in the South it continued as a key part of the agricultural economy. Cotton in particular proved particularly lucrative, with vast amounts of it being exported to North West England, where it would be received at the port of Liverpool before being processed in the cotton mills of Lancashire.

The issue of slavery drove a wedge between the free states in the North and the slave states in the South. The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860, who wasn’t even on the ballot in ten of the slave states, was the final straw for many Southerners. Throughout early 1861, Southern states announced that they were seceding from the Union, and soldiers loyal to their states began to seize forts from federal troops. In February, seven of the Southern states formed the Confederate States of America and inaugurated Jefferson Davies as their president.

From the start, the Confederacy made their intentions on slavery clear. Their constitution was largely a copy and paste job of the US one, with several key differences. For example, Article I Section 9(4) states:

No bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.

If that wasn’t enough to convince people how dear the institution of slavery was to the Confederates, the Confederate Vice President Alexander H Stephens on March 21st:

Our new government[‘s]…foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.

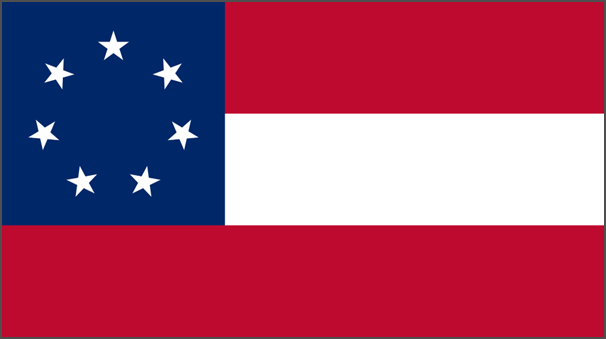

As well as defending slavery, the Confederacy also adopted their first flag, known as the Stars and Bars.

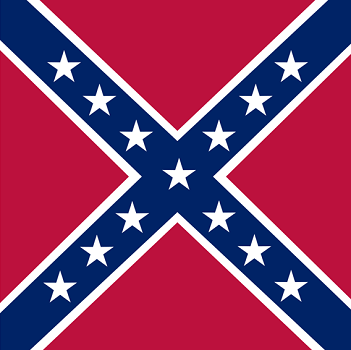

With the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, Charleston on April 12th 1861, the American Civil War was underway. Confederate armies fought under their own flags, the most popular one being the battle flag of the army of Northern Virginia.

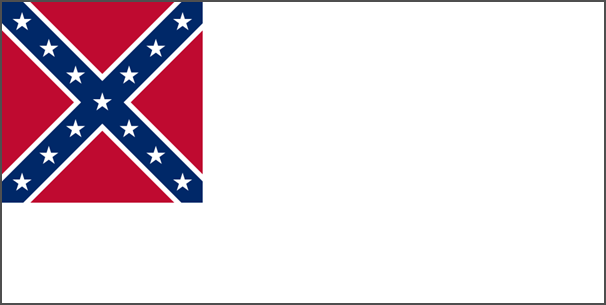

Once the Confederates realised that their Stars and Bars was too similar to the Union Stars and Stripes, they looked for a replacement. They took the popular battle flag and placed it in the canton of a white field to create the Stainless Banner. Why white? To represent the superiority of the white race. In the words of Savannah Daily Morning News editor William Tappan Thompson:

As a people, we are fighting to maintain the heaven ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored race: a white flag would thus be emblematical of our cause.

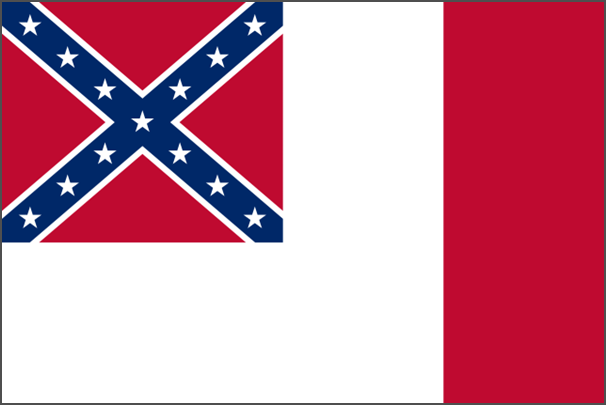

However, the Stainless Banner proved problematic, as they were marching into battle with a flag that was mostly white, giving the impression that they were surrendering. To fix this problem, they took the Stainless Banner and shoved a red stripe on the end, creating the Blood Stained Banner.

Liverpool and the Confederacy

But what was Liverpool’s role in all this? It’s easy to think of the American Civil War as something that happened “over there” but it had huge ramifications for British industry. The Union navy blockaded Confederate ports, meaning that the cotton that the economy of the North West of England relied on couldn’t get through. The cotton factories ceased to function, causing immense hardship in what was known as the “Cotton Famine”. Although Britain was officially neutral in the conflict, the Confederacy had a lot of sympathy in Liverpool. In 1864 and with the Confederacy struggling in the war, Liverpool held the “Southern Bazaar” in Saint George’s Hall, raising over £20,000 for the cause.

Once the war was over, the historical revisionism started almost immediately. The “Lost Cause” myth was perpetuated, claiming that the South’s cause was noble and that the war wasn’t about slavery. Monuments to confederates sprang up, and over time films and books emerged that played down the evils of slavery and romanticised the Southern lifestyle, most notably 1939’s Gone With The Wind. 1979 saw the release of the TV series The Dukes of Hazzard. The show featured a car called the General Lee, which sported a confederate battle flag on its roof.

All this revisionism has had an effect on the American perception of the war. A 2011 survey carried out by the Pew Research Center asked Americans what the primary cause of the civil war was. 48% said it was mostly about states’ rights, whereas only 38% gave the correct answer, saying it was mostly about slavery.

Although Confederate symbols such as the battle flag can be seen at far-right rallies in the USA, they are seldom seen elsewhere. In Italy, football fans in the south of the country sometimes fly the battle flag, simply because they are in “the South” and have a rivalry with “the North”. However, there exists a substantial number of plaques and even buildings dedicated to the Confederacy at Liverpool’s Rumford Place.

The Rumford Place plaques

Rumford Place isn’t exactly on the well-beaten tourist trail, but it’s a stone’s throw from Moorfields train station and easy to find when you know where to look. The first thing you are greeted by is a sign featuring three portraits.

The sign features the flag of South Carolina on the left, the first version of the Stars and Bars on the right, and three portraits. The president is Jefferson Davis, the first and only president of the Confederacy. The agent is James Dunwoody Bulloch, the man the Confederacy sent to Liverpool to procure warships for the Confederate navy. The master is Raphael Semmes, captain of the CSS Alabama, a Confederate commerce raider.

The street also features a couple of memorial plaques, one dedicated to the memory of all that fought on the CSS Shenandoah, another commerce raider.

Not only is it strange to describe those who largely attacked unarmed whaling ships as “brave”, it’s also worth noting the flags on this plaque. It features the British Union Flag and the American Stars and Stripes, it also has the Confederate Stainless Banner, the one that’s mostly white to represent the superiority of the white race. One thing it fails to mention about the Shenandoah is that it saw the last action of the war in Liverpool on November 6th 1865. Unaware that the war was over, it continued to attack merchant ships. Realising that they were now little more than pirates, they decided that it was best to stow their guns and surrender.

Each house in Rumford Place is named after something to do with the Confederacy, but the most interesting one is Enrica house.

Note that it doesn’t feature a Confederate flag, but the flag of the British merchant navy. Over on the other side of the Wirral, a ship called the Enrica was built at Birkenhead. It sailed under the flag of the British merchant navy to the Azores, where it was refitted as a warship, given confederate flags, and renamed the CSS Alabama. The plaque therefore celebrates the violation of the laws on neutrality so that the Confederates could get their hands on another commerce raider.

You may be thinking that these plaques have been around for some time. However, one of the plaques states that it was a gift from the great granddaughter of James Dunwoody Bulloch and unveiled in 2010. The plaque with the Stainless Banner was given for the 150th anniversary of the surrender of the Shenandoah in 2015.

So what can be done? Here is my proposal: a few streets away from Rumford Place is the International Slavery Museum, Liverpool’s attempt to come to terms with its unpleasant past. It’s there for education, so why not move all the plaques from Rumford Place there to create a new exhibit? Then we can rename all the buildings in Rumford Place to honour the real heroes of the American Civil War, people like Harriet Tubbman, Robert Smalls and Frederick Douglass, to name but a few.

Monuments to slavery and white supremacy should have no place in our cities, and it’s time we did something about them.