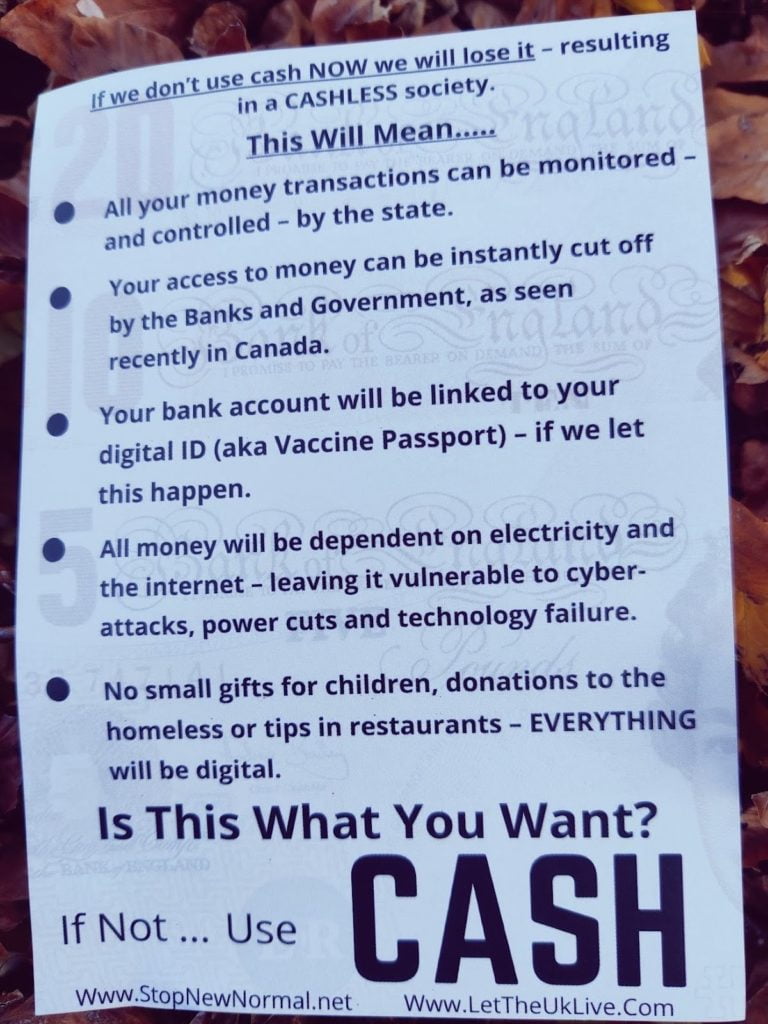

On a rainy evening in Liverpool this winter I was handed a leaflet by an earnest middle-aged activist, warning me of the dangers of a cashless society.

I followed the links and found that led to the websites of the anti-vax, climate change denying former London mayoral candidate, Piers Corbyn. Piers, who according to his website homepage has 16 Covid arrests (like this one), could be the subject of an article to himself, but I was intrigued by his focus on using cash in this leaflet.

Conspiracy theorists have a long-standing interest in banking, bank notes, fiat currencies and the gold standard. This fixation is currently best embodied by the worries about Central Bank Digital Currencies, which have – like any truly popular conspiracy theory – found their way onto graffiti on motorway bridges in the UK.

A Central Bank Digital Currency – commonly shortened to CBDC – is “a digital currency issued by a central bank, rather than by a commercial bank”, though it should be noted that the concept, as the Wikipedia article quoted above notes, is not well-defined. CBDCs are in use or set to be launched in five territories, including the giant economies of India and Nigeria. A further 80 central banks, including the Bank of England, are considering such a move in the near future.

Without getting too bogged down in the minutiae, much of what seems to worry people about CBDCs is pretty-well summed up in the above flyer. But what are the actual risks of digital currencies and a cashless society, and are people right to be worried?

First up – are we, as the leaflet says, headed for a cashless society, whether via CBDCs or otherwise? Sweden has famously been highlighted as heading in that direction for more than a decade, though it has not needed CBDCs to get there, nor has it yet actually become cashless, despite breathless articles claiming that the nation will be cashless by as early as this year. Articles which confusingly note that “consumer payments with cash are less than 20 percent of total transactions.” Twenty percent is, rather famously, a whole lot more than zero.

Nonetheless, it is the case that cash transactions are increasingly rare in Sweden, and many shops and services in Sweden require the use of mobile apps or plastic. For example, it is somewhere between very hard and practically impossible to pay for public transport with cash in Sweden. Clearly a cashless society presents a threat of exclusion for groups such as homeless people, for whom there are significant barriers to opening a bank account.

Some banks do offer bank accounts for people without a fixed address, you can purchase a Big Issue from many vendors with iZettle, and mobile to mobile solutions offer an alternative to banking (for example, 94% of homeless people in the US do own mobile phones), but obviously these all present a greater barrier than plain old notes and coins.

A cashless society would therefore clearly need to ensure payment services were available to everyone, including the most marginalised groups. While Sweden is touted as heading in that direction – though clearly it is not there yet – might the UK go cashless? No, at least according to the Bank of England:

We know being able to use cash is important for many people. That’s why we will continue to issue it for as long as people want to keep using it.

What of the other worries in this leaflet? Sweden once again acts as an example with regard to small gifts for children: transfers to children (or between any individuals) can be made by Swish, an almost ubiquitous mobile payment app in Sweden.

As for tipping, we need not look any further than the UK for this; many dining establishments already offer tipping via card, or when paying remotely using the restaurant’s mobile app. Have Piers and his mates been to a restaurant recently?

It is true that digital money is vulnerable to electricity outages and cyber-attacks… but this is already true of our current system, and it has been for a very long time. In the UK, we may only have seen cash fall behind debit cards in terms of transaction volumes relatively recently, in 2017, but how many decades has it been since the average pay cheque was an envelope containing an actual cheque or hard cash, rather than a bank transfer? How many people buy high-value items like white goods or electronics with cash, never mind a car or a house?

We have been vulnerable to cataclysmic cyber-attacks and technology failure for years, so unless Piers Corbyn is advocating bundling a large percentage of your money under your mattress, you’re unlikely to have enough cash to make a difference if the banking system does go down. And if the banking system goes down quite that comprehensively and permanently, we are probably in a sufficiently apocalyptic situation that we will have a lot more to worry about than paper money, which is also – lest our cash advocates forget – just an agreed-upon means of exchange with no inherent worth. Unless the authors of this leaflet think we all have enough wealth to store bags of Krugerrands under our floorboards, and, presumably, the means to defend our hoard when this digitally-enabled apocalypse arrives.

Regarding their concerns that bank accounts will be linked with digital ID and vaccine passports, my first reaction is surprise that there are still people banging on about vaccine passports. Very few countries still require vaccination for entry, and the few that do are now thinking again. The requirement for UK residents to verify their vaccination status to access services has also effectively vanished. Why do conspiracy theorists think they got this right?

While the UK government is apparently looking at digital ID – and the UK has historically gone a very different route from most developed countries on identity cards – the idea that your identity doesn’t already need to be verified to access banking is absurd. Here in the UK, in order to deter money laundering, banks are required by law to verify a potential customers’ identity, in order to comply with Know your Customer (KYC) regulations. This is to make sure that terrorists and criminals cannot use financial services to move around money and make it harder to trace.

This is not new in the UK: I can find references on know-your-customer rules for banks going back at least as far as the Money Laundering Regulations 1993.

Most of us are against money laundering to fund criminal activity, but what about the claims that the state could cut off our money, and that all of our transactions could be being monitored and controlled by the state?

The leaflet’s reference to Canada is presumably referring to the freezing of donations to support anti-vax truckers in Canada in the so-called “Freedom Convoy” protests in early 2022. The Canadian government did indeed freeze funds donated to protestors, and even the accounts of donors, which is obviously a pretty sinister move, and probably crosses a line even for those of us who disagree vehemently with the anti-vax protestors. However, this was done by court order and the Emergency Powers Act, so was all possible with any standard bank account linked into modern payment and transactions systems. The only option cash would have given is if the geographically-dispersed donors had stuffed notes into envelopes and sent it to the protestors in the post, which has not been a recommended way to send money… ever, as far as I’m aware.

As for the state monitoring and controlling our finances more generally, this comes back to concerns around Central Bank Digital Currencies. While there are many claimed benefits to CBDCs – financial inclusion by allowing all citizens a bank account; reducing or eliminating transaction fees; combating tax evasion and crime – there are several risks around privacy and surveillance that could cause concern.

In theory, a digital currency could make population surveillance more straightforward, and it has been suggested that citizens who do undesirable things could find their accounts cut off, and that certain behaviour – such as purchasing alcohol or pornography, or donating to an anti-government NGO or opposition political party – could be banned or lead to other state-imposed sanctions on your personal freedoms or finances.

Advocates suggest that CBDCs actually offer better protection for users, as China’s digital RMB – for example – will offer near-field transactions for lower-value amounts that do not involve an internet connection at all. Other nations are already looking at data protection and privacy for digital currency, including the USA and the UK.

We may not give governments much credence for such claimed protections, and it is not hard to imagine the authorities using the features of digital currencies for insidious purposes. However, so much of what is feared is already possible without digital currency: Russia closed down the bank accounts of anti-government opposition figures years ago; Sweden, Finland and Norway all restrict the sale of high-alcohol drinks through government-run monopolies; religious groups are already successfully campaigning to stop financial providers working with sex-related businesses.

If you’re in a country where the law already requires warrants or other legal authorisation for the state to go snooping on your private information such as your financial transactions, that’s likely to be the case with digital currency, whatever form it takes. Some have argued that the individual protections from such surveillance are not strong enough in countries like the UK, where examples of overreach range from exposing journalists’ sources to the use of powers to investigate petty matters like fly-tipping, but again these are already a problem under current legislation.

Central Bank Digital Currencies are a tool. What matters are the political decisions taken in their implementation, and the drafting of hopefully sensible laws to govern their use. Whether our politicians and such laws are up to the task is of course up for debate.

While CBDCs could absolutely be used for oppressive purposes, so can (and are) the regular financial and legal systems we’ve been part of for decades. Declining to tip on your debit card and insisting on leaving a sweaty pile of coins on the table in the restaurant isn’t going to change that, but diligent electoral scrutiny can potentially moderate it.