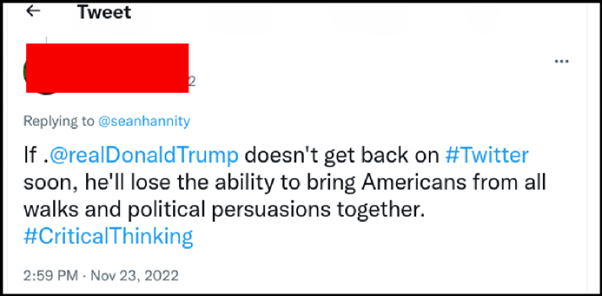

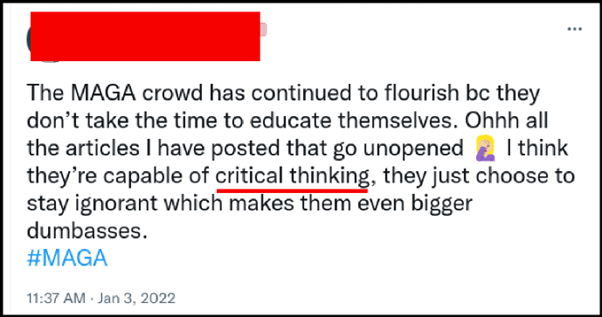

At the time this article was written, #criticalthinking was used 100 times on Twitter in the previous 24 hours. It had the potential to reach almost half a million users. So if the concept of critical thinking is so popular, why aren’t we making any progress toward general consensus on controversial subjects?

Part of the answer lies in these two tweets:

Clearly the two tweets both suggest critical thinking is the solution to the problem, but from the opposite sides of the argument. How is it that we all claim to be implementing critical thinking and we are all coming to different conclusions?

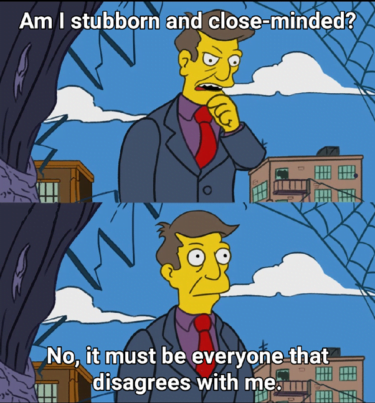

The answer is that our cognitive biases interfere with our ability to be truly critical in our thinking. This is not a new concept. Without looking too hard, we can find examples of this in modern literature, recent psychological publications and neurological research. So, what do we do? Throw up our hands and accept that we are destined to disagree? Allow every debate to devolve into a fist fight? Swear off of holidays with the family?

That would be the easy solution, but if our goal is to attempt to achieve some sort of consensus, then I suggest that we adopt a more challenging strategy. First, we alter our approach to changing people’s minds. That one is much easier than the second aspect of the strategy which is to look honestly at our own perspectives.

In order to change people’s minds, facts are not as helpful as you might think. More important than the content of what you say is how you say it. If you have heard Megan Phelps Roper talk about her time with the hate-group the Westboro Baptist Church, she describes their confrontational approach as based on the idea that if they present their truth, God will soften people’s hearts. To them, it does not matter how offensive or insulting they may be; once the idea is presented, the rest is up to God. I feel that many of us approach conversations the same way: my job is to lay the facts at my opponent’s feet and then they will see the error of their ways and agree that my perspective is the correct one. Of course, that rarely happens.

When we use aggressive language, when it is obvious that we are not listening to the other person, and when we are dismissive or don’t address their ideas, the other person responds by shutting down or adopting a defensive stance. Either way, they don’t hear our perspective, no matter how well-crafted our argument or how accurate our facts may be.

But what if they are wrong and I am right? It doesn’t matter. No matter how wrong they may be, their mind will not change with a simple presentation of facts. Instead of treating the conversation like a battle to be won, treat it like a conversation. In a conversation we share ideas and there is a back-and-forth. Listen – actually listen – to their perspective. Find points that you can agree with (no matter how difficult it may be). Rephrase and repeat their assertions. Be gracious and polite, as if you are concerned for the other person’s feelings.

Don’t try and change their mind; instead make your goal that they walk away with some piece of information they did not previously have, so that they can consider it at their own pace and convenience. Don’t interrupt them, allow them to feel that they are heard. Don’t belittle or demean either them or their talking points. Don’t make the conversation feel like an interrogation.

The second point of attempting to achieve some consensus is to look at our own beliefs. This is significantly more difficult than changing someone else’s mind, because the easiest person to fool is ourselves. The first step is to honestly consider why we hold the beliefs that we do. Is it because we had all the various perspectives laid out before us in an orderly and systematic fashion, and we chose the one that contained the most consistent and rational arguments? Or is the reason we hold a belief something more trivial? Do we hold the belief because it was the first one that was presented to us? Because it came along at a time when we were receptive to new ideas? Because someone we admire holds the same belief? Rarely is it the case that we held one belief, and someone debated us out of our position and into theirs.

Being wrong is emotionally debilitating and so we are hardwired to avoid that sensation, especially when there is someone to witness our acknowledgement of erroneous belief. Changing of minds typically occurs when our attention is elsewhere. One moment we are adherents to one belief and the next moment we notice that our opinion has shifted to a different point of view. When that happens, we often congratulate ourselves on our open-mindedness and willingness to adopt new opinions, but in reality the shift happened beyond our conscious mind, and so it could be argued that we deserve none of the credit.

Consider one of the perspectives that you have on a topic that is contentious, and not yet settled. How well do you actually understand the issue? Why do you hold that position? What would it take to change your mind? The last question is particularly insightful into how tightly we hold onto our beliefs.

Take, for example, the origins of COVID-19, and ask those three previous questions of yourself. Would it take an admission of guilt from a high-ranking health official, or an official acknowledgement of involvement from the Chinese government? Would you be willing to adjust your opinion if there were significant information that contradicted the official account? Perform the same exercise with the question of fraud in the 2020 US Presidential election. Consider another issue that is particularly contentious in your life and, as I said previously, pay particular attention to the third question: what would it take to change your mind?

If an acquaintance casually mentions an opinion that contradicts your own, do you immediately dismiss it, or do you ask them to elaborate so that you can consider the validity of the opinion? When a report comes to light that questions the integrity of your trusted source, do you immediately dismiss it or look for confirmation?

The human species is wired to create an “us” and a “them.” This strategy has ensured our survival, yet it is also the cause of nearly all of our conflicts. In times of peace, we are unable to turn off the instinct towards tribalism, and so we must develop internal mechanisms that will override that instinct. Without the overrides, everyone who agrees with us is our friend, and everyone else is our enemy, and we will never achieve any sort of consensus.