On October 14, 1921, readers of the The Daily Mail encountered a brief, strange entry titled The Unseen Hands by a contributor named T. Gifford. An article of less than 500 words would captivate thousands and eventually millions as unseen hands steered the narrative from implausible anecdote to entrenched folklore.

It seems strange that such a lonely place as the moors of Devon ended up haunting me as a kid all the way over here in the United States, but as readers are surely aware, those bleak and grassy hills have as many legends as bogs. Arthur Conan Doyle set The Hound of the Baskervilles in the Dartmoor moorlands. “Alien Big Cats” are said to roam the landscape. Local pubs and manor houses are alleged to be haunted. Some claim that the Devil himself once romped across the roofs of the area. So, perhaps it’s not that surprising that even the roads of this region have accrued legendary supernatural menace over the years.

Still, as legends go, the gripping story of the disembodied “hairy hands” of Devon is rather peculiar and I recently decided to dig in to find out more about its origins. What I discovered was a spectacular example of how an odd piece of tabloid news can become beloved local folklore.

I’ll give a brief summary of the legend as it is usually told, but there are many variants out there now in podcast and video form in addition to books that have cataloged versions. The story has grown less obscure than when I first encountered it in the 1980s, but it has also evolved and rarely is the root source of the tale explored. But before we dive into folklore forensics, let’s tell the legend as you’ll likely hear it today.

In the 1920s a doctor was traveling by motorbike with some children in his sidecar near the village of Postbridge in Dartmoor. He was on his way to Dartmoor prison to deal with a medical emergency, with the prison’s warden being the father of the two passengers. As he drove along he suddenly found that his handlebars were being gripped by two powerful, invisible, hairy hands and he shouted to the children that they should jump. They did so, just in time to avoid the horrific crash as the doctor lost his battle with the invisible hands and the motorbike crashed killing the driver instantly. Subsequently, other motorists also had unusual crashes, often as the result of these malevolent disembodied appendages!

Like many skeptical investigators, I often start with the obvious question: “Is this story true?” I usually begin an investigation trying to find the source material for the legend. In this case, a couple of books were responsible for the late-20th century popularizing the legend, both by folklorists who did a lot of work collecting legends of the region.

Theo Brown’s book Devon Ghosts (1982) and Ruth E. St. Leger-Gordon’s Witchcraft and Folklore of Dartmoor (1965) both carried prominent chapters about the legendary case of the hairy hands. Brown also wrote about the case in her 1973 collection of local stories, Tales of a Dartmoor Village: Some Preliminary Notes on the Folklore of Postbridge. These works capture the basics of the narrative as it stood in the latter half of the 20th century, including various versions and with the added feature that the hairy hands were sometimes seen by witnesses or experiencers.

But by this point, the transmogrifying effect of oral transmission had wrought changes to the original tale. I wanted to go back to the source material and then work my way forward, because it’s easier to see the familiar pattern of story transformation when you can find the origin tale. Let me add here that I don’t think that’s a sign of intentional deception. Stories change in the retelling, and our memories (though beloved by most of us for their reliability) are forever changing as we recall and transmit their contents.

To get to the source of the story we need to travel back in time to 1921, and give a bit of cultural context to both the natural and supernatural state of things at the time. First, it was a time when innovations in automobiles had led to their wider use in England. In the summer of 1921, there was a spate of motor accidents that led to large newspaper coverage and something akin to a moral panic around the dangers of driving. Innovations like seatbelts and 4-wheel hydraulic brakes would eventually arrive, but some quite dangerous vehicles on less than perfect roads had lethal consequences. Lurid stories of wrecks and angry opinion letters were common throughout 1921.

Much is made of the road itself in retellings of this story. The Postbridge road (now the B3212) crosses rolling countryside. Allegedly, after the public arousal around this series of news stories, the camber of that road was adjusted and the accidents stopped. However, to better understand this story we need to travel not in space, but in time. We need to know the historical cultural context from which this story emerges.

This was also a time when Spiritualism and Theosophy were incredibly popular. Multiple spiritualist newspapers were sustained by an enthusiastic readership, and no less a personage than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had become famous for his promotion of the ideas of this faith, especially that we are surrounded by spirits and psychic forces. Doyle had been evolving in his beliefs since the 1880s, but by 1920 was well known enough for his ideas around this topic to be spoofed in a stage act.

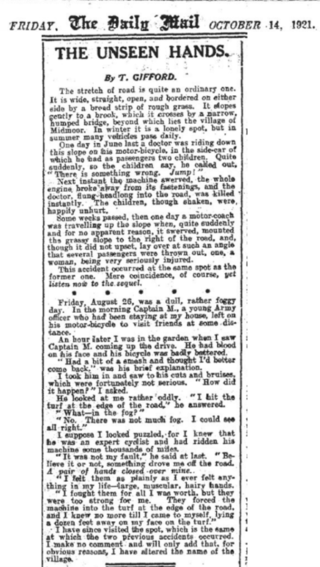

On October 14, 1921 the public concern over road safety and the world of the spiritualists would crash together in the pages of The Daily Mail (page 9). A story written by a “T. Gifford” told a strange tale of a young unnamed motorcyclist who wrecked his vehicle due to the unexpected influence of a pair of invisible hairy hands which had caused him to crash into the turf on the side of the road near the village of “Midmoor” (a pseudonym for Postbridge). The story reads:

THE UNSEEN HANDS by T. Gifford

The stretch of road is quite an ordinary one. It is wide, straight, open and bordered on either side by a broad strip of rough grass. It slopes gently to a brook, which it crosses by a narrow humped bridge, beyond which lies the village of Midmoor. In winter it is a lonely spot, but in summer many vehicles pass daily.

One day in June last a doctor was riding down this slope on his motor-bicycle, in the side-car of which he had as passengers two children. Quite suddenly, so the children say, he called out, “There is something wrong. Jump!”

Next instant, the machine swerved, the whole engine broke away from its fastenings, and the doctor, flung headlong into the road, was killed instantly. The children, though shaken, were happily unhurt.

Some weeks passed, then one day a motor-coach was traveling up the slope when, quite suddenly and for no apparent reason, it swerved, mounted the grassy slope to the right of the road, and, though it did not upset, lay over at such an angle that several passengers were thrown out, one, a woman, being very seriously injured.

This accident occurred at the same spot as the former one. Mere coincidence, of course, yet listen now to the sequel.

Friday, August 26, was a dull, rather foggy day. In the morning Captain M., a young army officer who had been staying at my house, left on his motor-bicycle to visit friends at some distance.

An hour later I was in the garden when I saw Captain M. coming up the drive. He had blood on his face and his bicycle was badly battered.

“Had a bit of a smash and thought I’d better come back,” was his brief explanation. I took him in and saw to his cuts and bruises which were fortunately not serious. “How did it happen?” I asked.

He looked at me rather oddly. “I hit the turf at the edge of the road,” he answered.

“What – in the fog?”

“No. There was not much fog. I could see all right.”

I suppose I looked puzzled, for I knew that he was an expert cyclist and had ridden his machine some thousands of miles.

“It was not my fault,” he said at last. “Believe it or not, something drove me off the road. A pair of hands covered mine. I felt them as plainly as I ever felt anything in my life – large, muscular, hairy hands.

“I fought them for all I was worth, but they were too strong for me. They forced the machine into the turf at the edge of the road and I knew no more till I came to myself, lying a dozen feet away on my face on the turf.” I have since visited the spot, which is the same at which the two previous accidents occurred. I make no comment and will only add that, for obvious reasons, I have altered the name of the village.

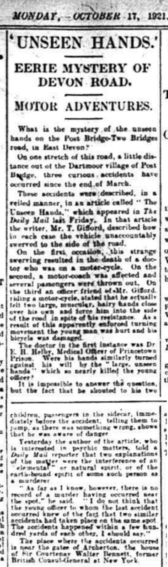

This initial story with its false names and anonymous characters caused quite a stir and, somewhat like a modern Internet story with lots of “likes,” the attention it garnered led to its being repeated across multiple newspapers. It generated a lot of mail as well, with people offering various explanations and similar experiences. On October 17th, the Mail offered a follow-up with names of some of the real places and characters being revealed. This follow-up was written by an unnamed Daily Mail staff writer who followed up with contributor Gifford who authored the original piece.

UNSEEN HANDS

EERIE MYSTERY OF DEVON ROAD

MOTOR ADVENTURES

What is the mystery of the unseen hands on the Post Bridge – Two Bridges Road in East Devon?

On one stretch of this road, a little distance out of the Dartmoor village of Post Bridge, three curious accidents have occurred since the end of March.

These accidents were described, in a veiled manner, in an article called “The Unseen Hands,” which appeared in The Daily Mail last Friday. In that article, Mr. T. Gifford, described how in each case the vehicle unaccountably swerved to the side of the road.

On this first occasion, this strange swerving resulted in the death of a doctor who was on a motor-cycle. On the second, a motor-coach was affected and several passengers were thrown out. On the third, an officer friend of Mr. Gifford riding a motor-cycle, stated that he actually felt two large, muscular, hairy hands close over his own and force him into the side of the road in spite of his resistance. As a result of this apparently enforced turning movement, the young man was hurt and his bicycle was damaged.

The doctor in the first instance was Dr. E. H. Helby, Medical Officer of Princetown Prison. Were his hands similarly turned against his will by the “large, unseen hands” which so nearly killed the young officer?

It is impossible to answer the question, but the fact that he shouted to his two children, passengers in the sidecar, immediately before the accident, telling them to jump, as there was something wrong, shows that he was aware of danger.

Yesterday the author of the article, who is interested in psychic matters, told a DAILY MAIL reporter that two explanations of the matter were the interference of an “elemental” or natural spirit, or of the earth-bound spirit of some such person as a murderer. [author’s note: see also elementaries]

“As far as I know, however, there is no record of a murder having occurred near the spot,” he said. “I do not think that the young officer to whom the last accident occurred knew of the fact that two similar accidents had taken place on the same spot. The accidents happened within a few hundred yards of each other. I should say.” The place where the accidents occurred is near the gates of Archerton, the house of Sir Courtenay Walter Bennet, former British Consul-General at New York.

Three motor accidents are mentioned in this follow up. We actually can find details on the first two of these and check them against the premise of the article, that these were all the product of supernatural influence of ghostly hairy hands.

The first accident refers to that of the wreck that ended with the demise of Dr. E. H. Helby. He was the medical officer at Dartmoor Prison. He was an interesting fellow, having served as a Navy medical officer on the HMS Immortalite in the 1870s. In 1909, when the suffragette movement led to women being imprisoned while agitating for the right to vote, some turned to hunger-strikes to add leverage to their cause. Dr. Helby became involved in in the force-feeding of women suffragette prisoners when they went on hunger strike in 1909 at the Winson Green Gaol. Despite those brushes with important historical moments, it’s his collision with the supernatural legend of the disembodied hands – a feature never a part of the original coverage of his crash – that has more clearly marked his place in history.

The story of Helby’s crash has many variations involving children and even his wife being passengers or onlookers to the accident. He and his wife don’t seem to have actually had any children according to public records, and it’s quite unclear if he actually had any passengers at all. These children serve a narrative purpose in the folklore in that they allow Dr. Helby an audience to shout his warning that he’s losing control of the motorbike (due to the influence of the accursed hairy hands?). The source of these two passengers may start with the newspaper The Scotsman, which carried the notice of his death on March 28, 1921:

Dr. Ernest Hasler Helby, Medical Officer, Dartmoor Prison, aged 51, received an extensive fracture of the skull through the breaking of a portion of a motor cycle while he was driving from Princetown to Tavistock. A verdict of accidental death was returned at the inquest on Saturday. The deceased’s two daughters were riding in the sidecar when the accident occurred.

To reconcile the lack of children, some versions explain that the children were the daughters of the Prison Governor at the time and that Helby had been taking the girls either to or from the prison.These claims never name the Prison Governor.

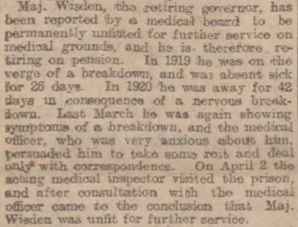

Records show that at the time of the accident, this position was held by Major Thomas Faulconer Mair Wisden. Dartmoor, at the time, was embroiled with scandals about the horrendous treatment of the prisoners, and by the time of this accident Wisden was already showing the signs of stress. Despite a long military career, the stress of life and perhaps the continued public scrutiny around the newspaper coverage of Dartmoor’s problems, he succumbed to a “nervous breakdown” and retired from public service in May of 1921.

Major Wisden, the retiring governor, has been reported by a medical board to be permanently unfitted for further service on medical grounds, and he is therefore retiring on pension. In 1919 he was on the verge of a breakdown, and was absent sick for 25 days. In 1920 he was away for 42 days in consequence of a nervous breakdown. Last March he was again showing symptoms of a breakdown, and the medical officer, who was very anxious about him, persuaded him to take some rest and deal only with correspondence. On April 2 the acting medical inspector visited the prison, and after consultation with the medical officer came to the conclusion that Major Wisden was unfit for further service.

When he died in 1935, Wisden’s obituary mentions a wife, a son and a daughter, not two daughters. I think it more likely that the Scotsman article just got these details wrong. It wasn’t unusual for errors like this to appear, as we’ll see when we look at the next accident.

But before we move on to the next motor accident we should note that more important part of the Scotsman article, which comes right after the wreck and months before Mr. Gifford’s associating the incident with any supernatural effects, gives the root cause as “the breaking of a portion of the motor cycle (sic).” While I do suspect errors in the article, Occam’s Razor suggests that a mechanical error is more likely than phantom hands being reported to phantom children to pass on the “true” cause of the accident. Even the Mail’s first follow-up article explicitly suggests that the hairy hands may have caused the motorcycle accident, whereas T. Gifford’s original mentions the mechanical failure and only implies the connection.

The next wreck mentioned is that of a Charabanc. These mammoth open-top vehicles were once the cruise-ships of the British roadway. Looking at some of the vintage photos of these vehicles with their rows of flat bench seating filled to the brim with city dwellers excited to go out and visit the English countryside, I can’t help but cringe when I think of the safety improvements that had yet to come to play in the automotive world at this time. Seatbelts, roll-cages, crumple-zones – none of these standard features existed yet. Even open-cockpit airplanes of the era lacked seatbelts, sometimes with tragic consequences (see Harriet Quimby).

Recall that in the original Daily Mail article, Gifford reported the Charabanc wreck like this:

Some weeks passed, then one day a motor-coach was traveling up the slope when, quite suddenly and for no apparent reason, it swerved, mounted the grassy slope to the right of the road, and, though it did not upset, lay over at such an angle that several passengers were thrown out, one, a woman, being very seriously injured.

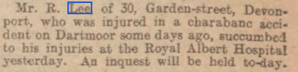

Other stories covering the Postbridge area and timeframe suggest that this wreck was the one reported in the August 25, 1921 issue of the Western Morning News. According to that article, a “spring broke, and the steering got out of control.” The accident threw 14 people out of the vehicle, pinning some underneath. One lady was reported seriously hurt. As I mentioned above, it’s hard to know how accurate these paper’s coverage was at the time. The original article reported a woman seriously hurt, but later coverage from September 14th reports that a Mr. R. Lee who had been injured in the accident, succumbed to his wounds. No mention is made of the injured woman who was singled out in the original coverage.

Mr. R. Lee of 30, Garden-Street, Davenport, who was injured in a charabanc accident on Dartmoor some days ago, succumbed to his injuries at the Royal Albert Hospital yesterday. An inquest will be held today.

It probably is worth noting that no mention is made of any disembodied hands: invisible, hirsute, or otherwise. Both Dr. Helby’s accident and the charabanc crash are attributed to mechanical failure of the mundane but tragic kind. That is, of course, until our spooky October news story from Mr. Gifford.

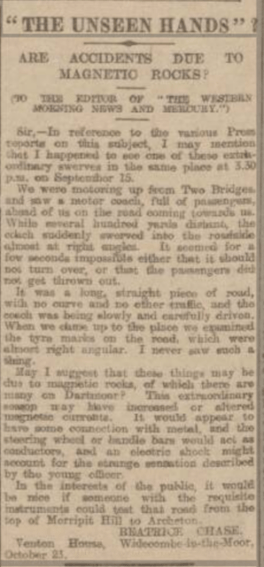

Once Gifford’s piece ran and the public began to respond, the story became a magnet for attention and opinion. Local Dartmoor writer Beatrice Chase wrote into the Western Morning News on October 24, 1921 to suggest that the spate of local accidents were attributable to the influence of “magnetic rocks.”

“The Unseen Hands”

Are Accidents Due To Magnetic Rocks?

(To the editor of The Western News and Mercury”)

Sir, In reference to the various Press reports on this subject, I may mention that I happened to see one of these extraordinary swerves in the same place at 3:30 p.m. on September 15th.

We were motoring up from Two Bridges and saw a motor coach, full of passengers, ahead of us on the road coming towards us. While several hundred yards distant, the coach suddenly swerved into the roadside almost at right angles. It seemed for a few seconds impossible either that it should not turn over, or that the passengers did not get thrown out.

It was a long, straight piece of road, with no curves and no other traffic, and the coach was being slowly and carefully driven. When we drove up to the place we examined the tyre marks on the road, which were almost right angular. I never saw such a thing.

May I suggest that these things may be due to magnetic rocks of which there are many on Dartmoor? This extraordinary season may have increased or altered magnetic currents. It would appear to have some connection with metal, and the steering wheel or handle bars would act as conductors, and an electric shock might account for the strange sensations described by the young officer.

In the interest of the public, it would be nice if someone with the requisite instruments could test that road from the top of Merripit HIll to Archerton.

Beatrice Chase

Venton House, Widecombe-in-the-Moor October 23 [1921].

Her suggestion was highly implausible, and scientifically informed writers quickly responded as much in the letters to the editor. But she certainly wasn’t alone in postulating supernatural or supernormal causes for these crashes.

As I noted above, the follow-up article in the Daily Mail made mention of terms from Spiritualism and Theosophy. The Spiritualist newspaper Light! From August 26, 1922 had a speculative explanation involving the disembodied will of the late Dr. Helby which had been trying to turn at the last moment being left tethered to that spot to continue to exert its last commands on future passing vehicles until it would eventually “exhaust itself gradually into other forms of energy.” This narrative of thought-forms and psychic influence was signed “P. H. F.” and it seems extremely likely after reading other submissions of his to the various Spiritualist publications, that this referred to the famous explorer Percy H. Fawcett.

The October 26, 1921 edition of the newspaper Truth – another spiritualist paper also carried the story and concurred with the “elemental” spirit being the probable cause. This article said that noted spiritualist Dr. Ellis Powell attributes the wrecks to “the partial materialisation of a ‘thought form originally generated by hatred, revenge, or lust’ in the presence of a ‘sensitive.'”

In 1932 the story would turn up again in the writings (and clipping-collections) of Charles H. Fort. In his book Wild Talents he recounts the news stories and the speculations about the possible causes. Fort also reported a fourth accident that had occurred on the same stretch of road in 1926:

The victim was traveling on his motor-cycle. “He was suddenly and violently unseated from his mount, and knew no more until he regained consciousness in a cottage, to which he had been carried, after a collapse.” The injured man could not explain.

By the 1960s the story of the unseen hands had become the folklore of the “hairy hands” and some versions didn’t mention their original invisibility at all. Pioneering folklorist (and Devon local) Theo Brown told the story in writing multiple times. One of the most interesting things about her coverage, which tells several people’s versions of the story, is that she includes a story that apparently came from her own mother’s experiences. In Devon Ghosts Brown describes how her own mother (adoptive) saw the hairy disembodied hands menacing her through the window of her caravan while camping out on the moors. This would have been around 1924, when Theo was about ten years old. According to her mother, a recitation of the Lord’s Prayer as well as making the sign of the cross was all it took to drive the monstrous hands away. Even though the story was retold to Theo decades later, it has the earmarks of classic sleep paralysis plus a hypnagogic dream.

1972 saw the publishing of The Witchcraft and Folklore of Dartmoor by Ruth E. St. Leger-Gordon. Her coverage of the case included some of the classic story elements as well as some of the Spiritualist explanations. She also alluded to a local “red monkey” which occasionally jumped out at people on a certain lane and that might also be a manifestation of a “hairy elemental.” Such entities she describes as “disembodied matter neither of the human nor of the spirit world, but earthbound between the two.” (pg 122)

In the decades since Theo Brown and Ruth E. St. Leger-Gordon wrote about these events, the stories have burgeoned from local to Internet folklore. They are the subject of numerous videos and podcasts, and appear in many books on the paranormal and weird. It’s a strange story.

After decades of researching such tales, I’m less interested in the scientific question of “is this story true” and more interested in the harder to answer question of “why is this story so popular.” From its very inception, the story of the unseen hands captured the public imagination and attracted speculation from every quarter as to how it might be explained.

But what is the explanation? The simplest explanation is that T. Gifford might have made up the story from thin air. We never find out who Captain M. might have been. In all the furor after the original story, he never comes forward. The two “previous wrecks” both have clear and mundane causes, with no need to add invisible, unmentioned, hairy hands. The context of the story coming from a time when such matters as Spiritualism and Theosophy were widely and publicly debated is lost in most modern retellings. The historical context of the case coming in the fall after a summer of frequent motor crashes is also rarely mentioned. We don’t have any scientific, reproducible evidence of invisible hairy hands but we do have plentiful evidence of legends being slapped onto real tragedy to see if it will stick. Tragedy collects legends the way black pants collect white cat hairs.

I do want to add that while the story shows a clear historical pattern of having started out as mundane wrecks being associated with legend, that doesn’t make it any less interesting to me. Far from it. The folklore that has been built up around this story is fascinating, varied, creepy, and relatively harmless. If it leads to people driving with moor caution, that’s fine by me.

As I mentioned in the introduction to this story, the moors of Devon are full of legends. Some have hypothesized that the connection between such folklore and the growing tourism business of the 20th century is more than coincidence. I don’t know if that’s true, but I do know that everything I’ve seen around Postbridge and the legendary haunting grounds of the hairy hands points to a beautiful destination for an excursion, and one that I hope someday to see myself.

References:

- Brown, Theo. “The Hairy Hand.” Tales of a Dartmoor Village: Some Preliminary Notes on the Folklore of Postbridge, The Devonshire Press Ltd, Torquay, 1973, pp. 26–28.

- Brown, Theo. “The Hairy Hands.” Devon Ghosts, Jarrold Color Publications, Norwich, 1982, pp. 95–99.

- “Charabanc Overturns.” Western Morning News and Western Daily Mercury, 25 Aug. 1921, pp. 5–5.

- Chase, Beatrice. “‘The Unseen Hands’ Are Accidents Due To Magnetic Rocks?” Western Morning News and Western Daily Mercury, 24 Oct. 1921, pp. 7–7.

- Cohen, Daniel. “The Hairy Hands.” Monsters You Never Heard Of, Pocket Books, New York, 1986, pp. 37–41.

- “Dartmoor Prison: Home Secretary and Recent Complaints.” Western Morning News and Western Daily Mercury, 4 May 1921, pp. 8–8.

- “Death of Major T. F. M. Wisden.” Mid-Sussex Times, 26 Nov. 1935, pp. 3–3.

- Fawcett, Percy H. “The ‘Hairy Hands of Dartmoor.’” Light: A Journal of Spiritual Progress and Psychical Research, 26 Aug. 1922, pp. 540–540.

- Fort, Charles. “Chapter 17.” Wild Talents, A & D Publishing, Radford, 2018.

- “Series of Motor Fatalities in England.” The Scotsman, 28 Mar. 1921, pp. 5–5.

- St. Leger-Gordon, Ruth E. “The Hairy Hands.” The Witchcraft and Folklore of Dartmoor, Peninsula Press, Newton Abbot, 1994, pp. 120–127.

- “The Unseen Hands.” The Daily Mail, 14 Oct. 1921, pp. 6–6.

- “Unseen Hands.” The Daily Mail, 17 Oct. 1921, pp. 9–9.

- “West of England News.” Western Morning News and Western Daily Mercury, 14 Sept. 1921, pp. 3–3.

Further reading on the relationship of Folklore and Tourism in Devon:

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233613488_The_Devil_on_Dartmoor

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/1257974

- https://www.academia.edu/34546861/Folklore_Fakelore_and_Tourism_in_Cornwall

—————————————–

I’m very grateful for the help of Bob Blaskewicz, Cian Gill, David S. Anderson, Jeb Card, Karen Stollznow and Mark Norman of The Folklore Podcast for their assistance with the research on this case.