Critical thinking requires us to hold an individual responsibility for evaluating information for its scientific rigor. Accepting something as fact just because someone in a position of authority says it is true is considered a logical fallacy, but it isn’t wise to always disregard the word of those with a demonstrated depth of knowledge in a subject. After all, critical thinking skills involve being able to understand where the limits of our own knowledge are too. Although it’s possible to spend time researching something we know little about to establish whether a claim is factual, sometimes we must rely on those considered as authorities in certain subjects to guide us.

It’s important then to have carefully considered, reliable criteria established for determining whether to accept or reject claims made by someone who appears to be an authority or an expert in a subject. When it comes to grassroots skepticism and science communication, it can be easy to accidentally jump onto the back of a popular meme or social media post which seems to be communicating a skeptical message as its heart when it’s not. To do so runs the risk of actually promoting misinformation – which runs opposite to what skepticism is all about.

For example, it is now a widely accepted fact that sometimes people think they have seen a lake monster or a sea monster when, in fact, they were observing the genitalia of a male whale in a state of arousal. Yes – a whale penis…

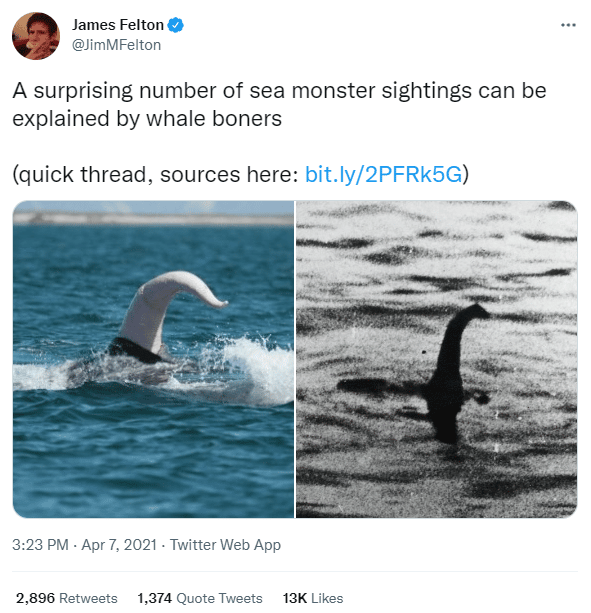

This alleged explanation for monsters was popularised by an ‘article on the ‘I f*cking love science’ website which was shared in an uncritical and viral twitter thread by comedian James Felton. Felton used a famous photo of the Loch Ness monster next to a photo of a whale penis to illustrate his point.

However, the Nessie photo in question already has an established explanation – it is a hoaxed photo from 1934 which some believe shows a small model monster affixed to a toy submarine. The photo appears to have been used by Felton because it fits so well with the alleged explanation being offered despite the fact it already has an explanation and is most certainly not whale genitalia.

As a paranormal researcher who uses scientific skepticism when investigating mysteries and paranormal claims, I have now seen the whale penis hypothesis offered up both by people who are and are not involved in the skeptic movement, and also by those who are both involved in paranormal research and the general public, too. In fact, an ex-colleague in the design office I used to work in once used it to mansplain lake monsters to me! To me and other skeptical paranormal researchers, it’s clear this idea has now been generally accepted, which is alarming as there is no scientific basis to the idea.

In his viral Twitter thread, James Felton elaborated that the explanation on offer came from 2005 research by Charles Paxton. Felton claimed that:

Charles Paxton took a look at this and other sightings of sea serpents back in 2005, for possible explanations of the accounts. They concluded – with comparisons to modern photographs and descriptions – that several accounts were actually of whale boners.

This is not true, and suggests that Felton did not check his sources. Paxton and colleagues conducted research into the 1734 sighting of a sea serpent off the coast of Greenland by Hans Egede. In their paper, they concluded that the sighting was:

likely to have been a whale either without flukes or possibly a male in a state of arousal.

Paxton and colleagues were open about the fact that this is speculation though, going on to state that their conclusion should not be used as a broad explanation for any historic or modern lake and sea monster sighting reports:

we have no “unmeet confidence [sic]” in our interpretation of the Egede creature. Nor are we suggesting that whales’ penises are a universal source of sea-serpent sightings.

Paxton et al, 2005

When it comes to exploring paranormal claims with the intention to find logical explanations for them, using one sensible sounding explanation to account for many or all instances of strange phenomena is irrational, because there are subtle details and differences in every case. More often than not, the simplest solutions are the right ones. People often mistake logs floating in Loch Ness as a serpent-like creature in the water, but a whale on its back would prove to be a very unlikely sight in such a location. Accepting at face value that whale penises are often mistaken for lake or sea monsters is the result of confirmation biases and a lapse in critical thinking skills. As a result, despite the research warning people to avoid generalising from the speculated explanation, that is exactly what has now happened.

As annoying as this is, it’s important to remember that everybody is susceptible to the sort of mental shortcuts which result in misinformation running wild, regardless of whether we believe in paranormal phenomena or not. In fact, many people involved in global skeptic movements happily shared this false information about whale penises causing lake monster sightings. In contrast, a lot of criticism of the idea actually came from those who promote the existence of lake monsters. This demonstrates that identifying as a skeptic is not enough to protect you from being irrational, just as knowing what logical fallacies are is not enough to stop you from acting and thinking in illogical ways.

The solution to these issues is simple: always try to avoid reacting to and sharing claims without first taking time to consider them (as tempting as the Retweet button may be), and don’t over-complicate things when it comes to critically evaluating information. For example, there are four questions that we can ask ourselves when we encounter a person on Twitter making claims before deciding to share it.

1. Is the Twitter account owner a genuine authority on the subject they’re writing about?

2. Is the Twitter account owner an expert in the specific claim or topic being discussed?

3. Does the Twitter account owner offer a verifiable source (e.g., academic paper)?

4. Do others who are considered an authority in the subject agree with the claims made?

If the answers to all of these four questions are “yes” then it’s probably okay to accept the claim that is being made (but only if you’re unable to verify the information further yourself). If the answer to any of these questions is “no”, then further research should be conducted before you accept the claim, and certainly before you share it.

In the case of the popular IFLS article and the subsequent viral Twitter thread from James Felton, the answer to all four of these questions is “no”. By stopping to consider these basic critical questions before hitting Retweet, a lot of people could have prevented themselves from spreading a Monster myth in the name of skeptical outreach.