I love cheese. I promise I’m not just going to continue exclusively writing articles about food stuffs I like, but last month’s chilli article did quite well so at least some of you enjoy reading it!

At the beginning of 2019, in the halcyon days pre-COVID-19, an article popped up from Tim Samuels headlined “Why cheese is no longer my friend”. It got some decent coverage on social media, which makes sense: it was January, around the time people start thinking about dieting after Christmas and the media starts pumping out more food related articles than usual. Tim explained:

While milk and dairy products, such as cheese and yoghurt, are good sources of protein and calcium and can form part of a healthy, balanced diet, as Dr Michael Greger, from NutritionFacts.org, put it to me: “There’s no animal on the planet that drinks milk after weaning – and then to drink milk of another species even doesn’t make any sense.”

Of course, there’s also no animal on the planet who makes and eats bread, makes, cooks and eats pizza, or makes their own chutney (all things enhanced with the addition of cheese, in my opinion).

Putting aside food, is the point that we should consider anything that humans do that other animals don’t do is illogical? If so, you wouldn’t be reading about Tim or Michael’s thoughts about cheese, as we’re also the only animals who speak, and tell stories in a memorable and specific order, and write down our thoughts, and who sit inside typing on computing equipment that only humans make. Tim and Michael ought to think twice before pulling at that particular thread.

The naturalistic fallacy isn’t the only reason not to eat cheese, according to the article, which explains that Dr Greger “reeled off a series of studies showing the life-shortening potential of drinking this “hormonal stew”.” At no point before or after this line in the article are hormones mentioned again. No justification, certainly no citations – nothing. We’re just meant to take “hormonal stew” as a fact, and a scary-sounding one at that.

Turning to Dr Greger’s own website, NutritionFacts.org – where you can, of course, buy a copy of his book “How Not to Die” – we’re told:

All animal-based foods contain sex steroid hormones, such as estrogen. These hormones naturally found even in organic cow’s milk may play a role in the various associations identified between dairy products and hormone-related conditions, including acne, diminished male reproductive potential, and premature puberty.

When it comes to cancer, leading experts have expressed concern that the hormones in dairy and other growth factors could potentially stimulate the growth of hormone-sensitive tumors. Experimental evidence also suggests that dairy may also promote the conversion of precancerous lesions or mutated cells into invasive cancers in vitro.

Of course, when it comes to which hormones people are worried about, it tends to be the predominantly (but not exclusively) female sex hormone, oestrogen that all the horror stories centre around. Because god forbid should anyone masculine encounter something in the slightest bit feminine, cos feminine is bad and won’t somebody please think of the children. There are all sorts of claims made about oestrogen, including that it can cause premature puberty, and that it might cause breast or prostate cancer.

One article in the Harvard Gazette even went so far as to say:

“The potential for risk is large. Natural estrogens are up to 100,000 times more potent than their environmental counterparts, such as the estrogen-like compounds in pesticides.

Among the routes of human exposure to estrogens, we are mostly concerned about cow’s milk, which contains considerable amounts of female sex hormones,” Ganmaa told her audience. Dairy, she added, accounts for 60 percent to 80 percent of estrogens consumed.”

This final claim may or may not be true – but what is missing is what total dairy is 60-80 percent of, whether that’s a large amount, and whether it makes any impact on the hormone concentration in the human body.

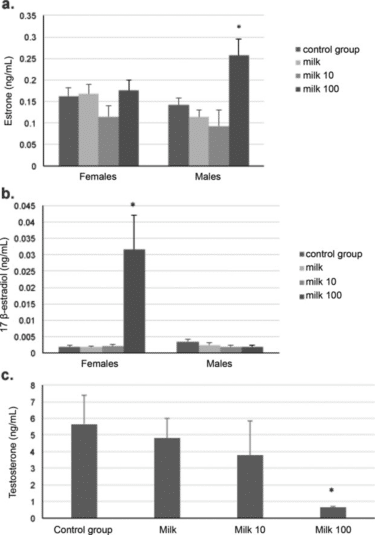

In 2016, a study looked into whether dietary dairy would increase the circulating levels of oestrogen in mice – the researchers took milk from pregnant cows that was claimed to have an increased level of oestrogen, and measured the concentration. The concentration was around 0.093 ng/mL. The researchers took some of this milk and added an extra 10ng/ml of oestrogen, and to another batch they added an extra 100ng/ml of oestrogen, and then they gave the different batches of milk to different groups of mice. The study included four groups: A control group, who were given just water; a group given normal, native, cow’s milk; a third group given cow’s milk with 100x more oestrogen and a fourth group given cow’s milk with 1000x more oestrogen.

The results showed that the only time levels of hormone changed in these mice was when they were given the massive overdose, containing 1000x more oestrogen than exists in cow’s milk – even pregnant cow’s milk. The 100x overdose had no effect, let alone the regular milk. Given that the amount of circulating hormone in mice who consumed pregnant cow’s milk was indistinguishable from mice who were given water, we can reasonably conclude that the mice probably aren’t being affected by the cow’s milk. This would need to be studied further in humans, but it does lend weight to the argument that consuming dairy doesn’t appreciably increase the level of these hormones in humans, either.

What also lends weight to the argument that these hormones aren’t presenting an elevated risk to humans is that there is no correlation between changes in dairy consumption – which has been decreasing over the last several years – and puberty ages, which have also been reducing over time. If hormones in milk were playing a role in puberty onset, we’d expect later puberty onset to correlate with a reduction in dairy consumption.

All of this makes perfect biological sense – oestrogens are steroid hormones which are metabolised by the liver. The liver detoxifies our body. Yes, I know Goop will tell you it’s coffee enemas, but the liver does the job. You would have to completely swamp the system before you’d start to see an appreciable difference in the body. Eating some cheese, or drinking some milk just isn’t going to do that.

There are some good reasons why you might not consume milk (including, but not limited to environmental and ethical reasons), and even some good reasons why some people might not consume it for their health.

As Tim mentions in his BBC article, when he was younger he was diagnosed with lactose intolerance. Something that sometimes can, but doesn’t always, disappear over time. Lactose intolerance can lead to symptoms ranging from mild gastrointestinal discomfort to full blown hellfire and fury inside your guts. It can also have all sorts of knock-on effects on your digestion and wellbeing. But even then, when Tim spoke to scientists who don’t have a book to sell, they all said more or less the same: that dairy isn’t some big bad. From Tim’s BBC article:

Dr Walter Willett, a professor of nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health – took a more semi-hard view of cheese. “It does not seem to have the same growth-promoting effects as milk does. Have your Brie in moderation and enjoy it.” He said we should have only one portion of dairy a day.” – which is basically saying, it’s not like you need it, but it’s fine if you like it.

Meanwhile Professor David Levitsky of Cornell said he has a small plate of cheese every evening before dinner.

Tim went to get his lactose intolerance checked out where his doctor, Dr Enam Abood from the Harley Street Health Centre, told him, that he is still lactose intolerant, but that he could take a lactase supplement and be able to consume cheese without causing damage to his guts. All of which is pretty moderate.

While the headline promised to tell us why Tim and cheese are no longer friends, the article itself concludes with:

I think about how bewildering it is to get definitive answers around nutrition. I think I should remember to carry around lactase enzyme pills. And I think my gut would want me to have a little slice of Roquefort… tomorrow.

Which, if you only skimmed the article or saw it circulating on social media, is not the conclusion you’d get from the sensationalist headline, nor the strong and entirely unsubstantiated claim that milk is a “hormonal stew”.

But, often, the best way to get clicks on your news story is to tell people that food is evil. The truth, that diet is highly personal and is not the golden bullet to cure all our health ills, is really rather dull.