As befits an article about cultural literacy, I want to start with my own personal cultural touchstone for understanding cultural literacy. A few months after Trump was elected president, my partner and I went to see the musical Come From Away, about the travelers diverted to Newfoundland when American airspace was closed after the attack on 9/11. I was skeptical of a 9/11 musical, having grown up desperately wishing that my society would stop living in the days immediately following the attack.

Instead of feeling awkward about the content, I cried through the entire two hour show. It turned out the show wasn’t about 9/11, or America, it was about the humanity of a community coming together to help strangers in need. After watching a malignant narcissist get elected as president on a platform of racism and lies, a show about people just helping each other with no thought of compensation absolutely broke me.

One moment in particular still kills me every time I listen to the cast recording. On one of the diverted flights, there’s an African family that is unable to communicate with anyone around them. When the flights are finally unloaded, they’re put on a bus headed for a shelter, but they don’t know that. All they can see is the pitch-black Canadian wilderness, and they’re simply terrified. The bus driver, desperate to put them at ease, notices the wife is carrying a bible. Asking for the bible, which he cannot read, the bus driver uses the numbering system to find a passage he has memorised. Philippians 4:6: Be anxious for nothing. He repeated those words to the family, be anxious for nothing. I’m a lifelong atheist, and it’s one of the most beautiful moments I’ve ever seen.

Beyond the overwhelming human compassion, the moment exemplifies, on many levels, the value of cultural literacy. The term “cultural literacy” was coined by the education theorist E.D. Hirsch and popularised through his 1987 book Cultural Literacy: What Americans Need to Know. Hirsch argues that education should emphasise greater awareness of important cultural touchstones, such as famous people, places, concepts, and phrases. Having a wealth of shared cultural references allows for richer art and a more robust sense of community. Communities require shared values and concern for other community members, but the language of community is often one of shared references.

Cultural literacy also allows for communication when other forms break down. The characters in Come From Away don’t share a language, but they share some cultural literacy, like a Rosetta stone waiting to bring people together. By drawing on a shared reference, they’re able to communicate more deeply and effectively than if they had simply spoken the same language. Cultural literacy provides one of the strongest foundations for genuine connection.

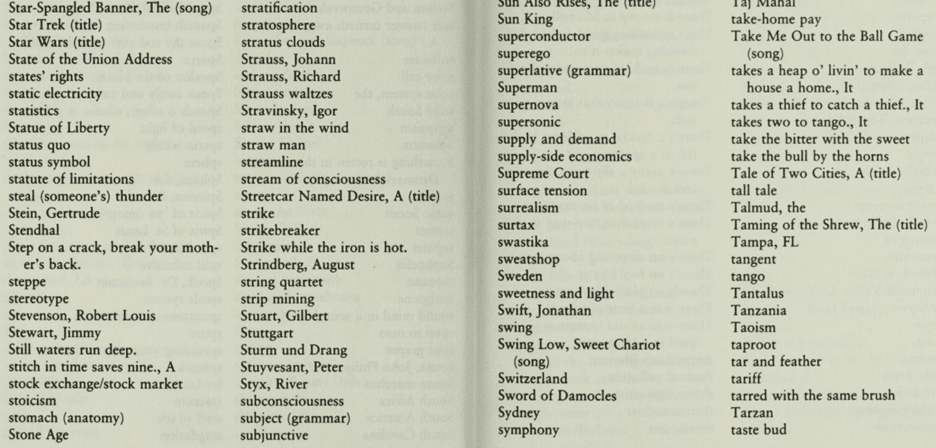

Hirsch’s theory of cultural literacy immediately sparked debates around culture and education that have only gotten worse as both communities and content production have balkanised. Every time we come back to debating whether to stick to the “Western canon”, or attempt to “diversify” and “decolonise” our curriculums, we’re debating tradeoffs around cultural literacy. Hirsch’s book includes an appendix listing 5,000 things that every American student should know about, including names like Hank Aaron and phrases like “abandon hope, all ye who enter here”, and it makes clear the overwhelming challenge of cultural literacy in the modern age. Here’s a random sample from the list:

How many of these would you have to google? How many of them strike you as genuinely essential? It shouldn’t surprise us that Hirsch’s list already feels out of date, and reflects the author’s own cultural predilections.

However, this raises a crucial question: when we say “cultural literacy”, what culture do we mean? Clearly it’s not just American culture, given how many things on that list aren’t American. Nor does “European” or even “Western” culture seem sufficient, given that Taoism and the Taj Mahal made the original list. So… world culture, then? But does that broadening-out dilute the concept down to a triviality?

It seems that cultural literacy will always be a vague moving target aimed at by individuals with cultural priorities and preferences. That reality has led some to condemn cultural literacy as colonialist education, aimed at assimilating students into a Eurocentric worldview, and to argue that we should abandon the idea entirely.

However, I don’t think abandoning the concept is possible. Cultural literacy is crucial to a life of flourishing, and students need to learn how to cope with that fact in the age of exponential content growth. Plus, schools need curriculums, and those curriculums have time constraints, so we have to make hard choices. I see two options here: either we try to maintain a set cultural canon, even in the face of exponential content growth; or we embrace as many cultural touchstones as possible and hope for the best.

The first option faces serious problems, akin to attempts by France and other countries to preserve the purity of their languages despite the constant onslaught of new things. First, you have to select the size of the canon. Too small, and there won’t even be room for new Western culture, much less the classics. Remember, Hirsch’s list was 5,000 items long, and that was in 1987, before the information age really took off and we started to generate content and data at exponential rates.

Keeping the list short might require picking a single Shakespeare play, a single Platonic dialogue, or a single Canterbury tale and leaving off the rest to make room for a more diverse range of references. It seems unlikely that this option would satisfy anyone. Furthermore, are we then going to pressure artists to draw on that limited canon in order to reinforce its legitimacy? This path seems destined for cultural stagnation.

The alternative is to embrace as many cultural touchstones as possible and hope for the best. Perhaps we create a very long list of options and leave it to teachers to decide whether to use anything on that list, or to make their own. This is the option I prefer as an educator. When I was younger, I would tell people “everyone needs to watch/read X”, but I’ve grown increasingly skeptical of such claims. I think we’re living in a post-canon world. There’s simply too much good content to make anything required for everyone. At best, there is some content I will strongly recommend to everyone I can, but it’s no longer reasonable to expect people to have the same cultural references. Some might consider this abandoning the concept of cultural literacy, but I see it as preserving the goal while being realistic about the path.

So, instead of sticking to a canon, I try to introduce my students to as many cultural touchstones as possible. Similarly, when I talk to folks, I make as many references as possible from as many things as possible, with the goal of making as many human connections as possible. Realistically, this means many references will go unnoticed, and sometimes people will have no idea what I’m talking about or think I’m weird, but that seems like an unavoidable reality. We already live in a culturally balkanised world, there’s no undoing that by forcing everyone to read the same thing. At best, we can encourage people to cast their cultural nets as widely as possible.

I started this article with a cultural reference that many of you were unlikely to recognise, and that’s okay. My goal was not just to provide an example of applied cultural literacy, it was to entice you to go watch the filmed version of Come From Away, or catch it in theaters if that’s an option for you.

Introducing someone to a new cultural reference point can be just as joyful as realising you already share a reference. We build our own shared cultures with those around us, and thankfully we have an embarrassment of riches to draw on. So, if you’re worried that human connection will be lost in the sea of new content, let me just say: be anxious for nothing.