If you ever have the chance to visit The International Museum and Library of the Conjuring, consider yourself very fortunate. For one thing, its location is kept secret (all we’re told is that it sits somewhere on the outskirts of Las Vegas). For another, attendance is invite-only. The curator and tour guide of the museum is David Copperfield, considered by many to be the most iconic magician of his generation.

Everything Copperfield does is big. Among his most legendary illusions, he has managed to make the Statue of Liberty disappear, walk through the Great Wall of China and fly. Superman himself would struggle to keep up.

Copperfield’s work has earned him 21 Emmys, 11 Guinness World Records and a fortune just north of the billion dollar mark. A good chunk of that money has been spent on the collection of magic memorabilia housed at his museum. Some estimates suggest a third of all historical magic items belong to this collection, many of them secured at auction (spare a thought for other afficionados who dare to bid against Copperfield).

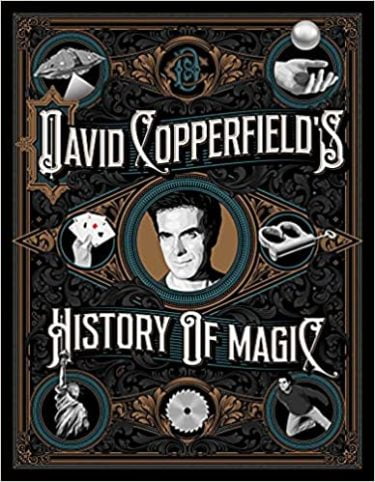

History of Magic, by David Copperfield, Richard Wiseman, and David Britland, is an attempt to share Copperfield’s treasures with the world and, with them, his insights into the craft he has devoted his life to.

The book stays faithful to its title. Like any trip to a museum, we’re invited to plumb the historical context that accompanies each item on show. Along the way, we’re treated to fascinating stories about the people and events that brought each item to prominence, and that inspired Copperfield include them in his collection. The book is beautifully illustrated, with over 100 high-resolution snaps giving readers plenty of pause to taken in the marvels Copperfield wants us to learn about.

History of Magic is less about how illusions work and more about why they mattered in their time and place. For instance, the authors walk us through a century of iterations on the classic sawing trick. This illusion first made a stage appearance a century ago, and there’s speculation its appeal had something to do with the battle-hardened mindset of audiences who were used to scenes of gore from World War I, as well as the suffragette movement, for which the death-defying stunt served as a symbol of female empowerment. The authors also note that the versions of the trick in play today are a world apart from the original. As society evolves, so does the magic that represents it. This renders magic an enterprise of continual refinement, as its proponents look to raise the bar (and shock levels).

Copperfield’s case for magic is anything but a hard sell. This is a warts-and-all presentation, with harrowing accounts of illusions gone wrong. The Bullet Catch (exactly what it sounds like) has claimed more than one victim, each circumstance as tragic as the next. The dark side of magic resides most of all in its potential for deceit, and the authors have no qualms in calling out the twentieth-century US illusionist Alexander Conlin as ‘the world’s most duplicitous and devious magician’ for weaponizing his craft as a means of claiming psychic abilities.

Ultimately, however, History of Magic reads as a tribute to the magician’s craft. It offers fond reflections on the fraternity among magicians, regaling us with stories of the affable Harry Blackstone, a ‘kindly and benevolent wizard’ who won audiences over with his charm and went out of his way to support his fellow magicians in need. Copperfield’s own love for magic may strike you as obsessive; from the accounts of this book he is far from alone. Quantum leaps of progress are made when magicians such as the sleight-of-hand artist Cardini are willing to expend painstaking amounts of effort to perfect their craft (Cardini’s left hand, we’re told, was left blistered and scarred as a result of his ceaseless attempts at cigarette manipulation).

The historical detail throughout the book is impressive, and the enthusiasm for illusion shines through the pages. It does read more like a textbook than a memoir at times, and Copperfield’s voice occasionally gets buried among the history lessons. We’re left to make our own inferences on what makes David Copperfield tick, although he does drop clues with some of the selected items. In trying to explain Arthur Loyd’s indexing systems, for instance, Copperfield concedes that even after his careful study of Loyd’s props, he remains mystified as to how the magician pulled off his stunts. For Copperfield, these relics of the past are clues to a never-ending quest of understanding the inner workings of his ancestral craftspeople. And while Copperfield boasts an original copy of the classic book The Expert at the Card Table, he is as oblivious as the rest of the magic community on the identity of its mystery author. Even magicians, it turns out, can be left perplexed.

This book doesn’t lift the lid on how your favourite illusion works. The greatest trick Copperfield and his co-authors have pulled off is to let you in on the wonders of magic (and its darker elements) without revealing any of its secrets. For the majority of us who won’t make it to the outskirts of Vegas, it’s a pretty good second prize.