Often, the difference between a conspiracy theory and the truth is who said it.

Let us look at Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370. The inconclusive search for the airliner and the lack of an official consensus regarding its disappearance has set the world buzzing for the truth. In the seven years since its disappearance, we have seen all manner of plausible-seeming theories put forward to explain the events that led to its disappearance. Some have posited that the disappearance was down to an onboard fire, like in Nigerian Airways Flight 2120. Others claim there was an airliner shootdown incident, like in Korean Air Lines Flight 007. Others still look to the pilot for answers. One thing was for certain – anything could have happened, and before we come to any conclusions as to what was most likely, we need more information.

As time went by, those looking to solve the mystery of the missing flight have grown increasingly disappointed by the lack of information and proactivity by the Malaysian government. To this day, the Ministry of Transport Malaysia (‘MOTM’) has not established an official cause of the incident, choosing instead to focus on recommendations that could prevent such an incident from happening in the future (Ministry of Transport Malaysia, 2017). Similar thoughts were echoed by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (‘ATSB’) in their final report. With the world left in the dark about what happened to MH370, we find ourselves overwhelmed by a myriad of alternative theories formulated by both experts and amateurs.

While interest in MH370’s disappearance has gradually faded over the past 7 years, a recent opportunity to speak to other aviation enthusiasts has renewed my interest in exploring the case for myself. While the natural course of action would be to speculate as to what happened, we must recognise that there are some theories that simply cannot be verified, due to a lack of evidence. Instead, we can focus on the theories that do claim to be based on evidence, to understand how conclusions, or a lack thereof, were drawn.

Let us begin by looking at three popular theories, which I will explore with the help of a pilot I spoke to, who for reasons of anonymity we can call “Pilot P”. Pilot P helped me understand each theory through the lens of someone who has plenty of flying experience, ranging from the most probable theory, to the least probable.

Theory 1: The Pilot

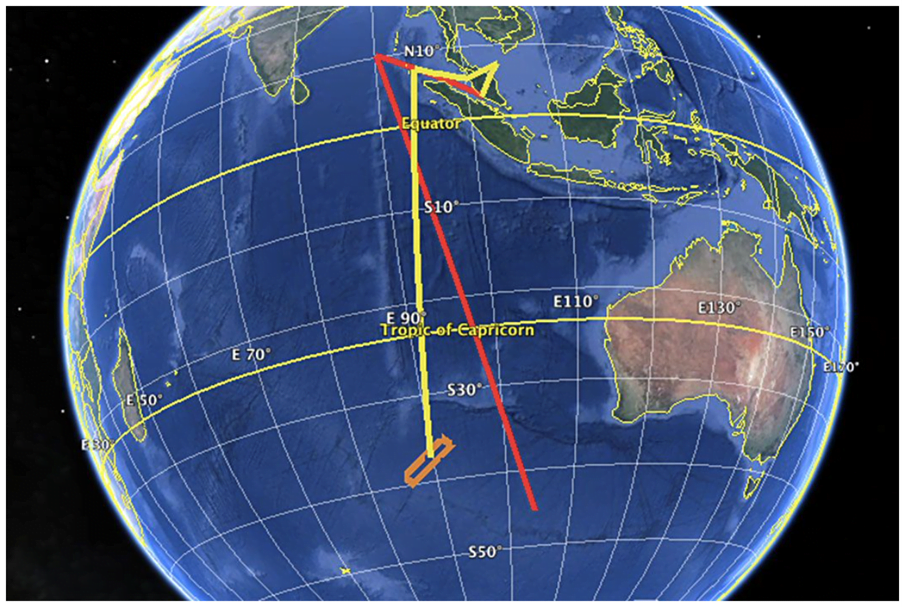

The first theory we will be dissecting is that the disappearance was due to a deliberate act by the pilot. Advocates claim that one of the pilots intentionally brought the plane down by first flying around Penang, then heading out and crashing the plane into the southern Indian Ocean. This is better illustrated with the official map detailing the known route that MH370 took.

According to this theory, the flight proceeded normally until there was a handover from Kuala Lumpur Area Control Centre (‘ACC’) to Ho Chi Minh ACC. Thereafter, Captain Zaharie Shah had his co-pilot leave the cockpit, perhaps under the guise of requiring him to check out some issue in the cabin. Captain Shah could then have locked his co-pilot out of the cockpit and depressurised the aircraft, knowing that, unlike in the passenger cabin, his cockpit oxygen supply could last for hours. He then donned his oxygen mask, switched off all communications with the ground and flew the plane for hours before eventually setting it down in the ocean (Kitching, 2019).

Advocates for this theory build their case as follows: Firstly, the pilot, who was from Penang, took a detour from the original route towards Beijing to circle around Penang island. According to Captain Simon Hardy, a veteran 777 pilot, this indicated that someone on board had intended to take “ a long, emotional look at Penang” (Westcott, 2015). As there were no other pilots on board according to the flight manifest, this points towards Captain Shah as the more likely pilot for the Penang detour.

Secondly, Captain Shah had allegedly flown on his home flight simulator six weeks prior to MH370 a flight plan that was ‘initially similar’ to the one actually taken. This is illustrated below:

As you can see, there are similarities between MH370’s presumed flight path in yellow, and Captain Shah’s simulated flight in red. The latter was reconstructed from 6 data points recovered from his home flight simulator (Australian Transport Safety Bureau, 2017). If this was the truth, it might provide compelling evidence to believe that the disaster was planned. However, it is important to note that this argument relies on the accuracy of the flight path, yet the Inmarsat data relied on to construct the plane’s actual flight path cannot confirm MH370’s exact location in real time, but provides an approximation spanning from Central Asia to the middle of the southern Indian Ocean (Langewiesche, 2019). There are many other articles that extensively analyse the available data, and many of them do come to the conclusion that the fact pattern makes it difficult to deny that the Penang detour was a deliberate act – whether by Captain Shah or his co-pilot.

Lastly, Captain Shah was an examiner for the same aircraft type as MH370, meaning that he may have more easily convinced his co-pilot to leave the cockpit under the guise of checking a malfunction in the cabin, given his extensive experience. This seems particularly compelling, as Pilot P told me that under most situations, departures from the cockpit are often on a need-to basis, such as using the lavatory or conducting of checks in the cabin. Therefore, if the co-pilot did leave the cockpit, it is likely to have been under the command of Captain Shah. In addition, Pilot P mentioned that the cockpit door can be locked manually from the inside, making re-entry impossible.

This seems to be the most compelling theory to me, and I can understand why it has gained traction. The impossibility of interrogating a deceased pilot, coupled with scant remains, has led to inferences that are as difficult to deny as they are to prove. However, it is easy to pin the blame on someone who is unable to take the stand and defend himself – a point Pilot P agreed with. We will never know what went through Captain Shah’s mind then, and it is unfair to pin the blame on him unless it can be proved.

Equally, while the evidence may appear persuasive, it relies on some very specific assumptions for the theory to hold true. Firstly, it would require extraordinary effort to descend and fly the plane unnoticed around the island of Penang, with the sole purpose of Captain Shah viewing the lights of Penang for one last time before crashing the plane down in the middle of the southern Indian Ocean. In my opinion, if what the captain really wanted was to crash the plane, it would be unnecessary for him to then fly the great length to the southern Indian Ocean – he could have brought the aircraft down in the South China Sea, the Andaman Sea, or anywhere else close by. The southern Indian Ocean seems too specific of a location.

Also, the pilot theory relies on a chain of assumptions that make it unlikely: first, the pilot must have been determined to crash the aircraft; second, the pilot must have successfully convinced the co-pilot to leave the cockpit; third, there had to be no traffic in the vicinity that would have noticed its deviation; fourth, there would have to be no fighter jets scrambled to intercept the plane as it was criss-crossing the Malaysia-Thailand border; and fifth, there would have to be no communication from the plane to the ground when the crew suspected something awry and still had time to react. That is a lot of unlikely scenarios that must happen in succession for the plot to work – in my opinion, it vastly lowers the likelihood of this theory.

Another reason the theory is unlikely is that the satellite data unit which maintains communication links had sent a log-on request to Inmarsat’s satellites after it had been switched off. It also sent hourly ‘handshake’ acknowledgements to those satellites. This meant that someone was in the cockpit and had control over communication links (Llewelyn, 2020). It is highly improbable that the plane would have continued its communication with satellites if it had been ‘hijacked’ by Captain Shah, given that a suicidal pilot would likely seek to hide his tracks by turning off all forms of communications and relying only on navigational aids. Hence, what we already know and have available as evidence do not cohere with the theory, and thus I think even this theory can be ruled out.

Theory 2: Aircraft malfunction

Let us now consider the second theory – aircraft malfunction. There are two variations within this theory: hypoxia – a fatal loss of oxygen – or a fire.

Hypoxia could have occurred intentionally, as described in the first theory, but it could also have been the result of an aircraft malfunction, such as the failure of the pilot to pressurise the aircraft. The latter is likely ruled out, as experienced pilots have stated that the tight turns made just as the plane approached Vietnamese air space had to be manually controlled (Supra n 3). Further, if the plane had issues with pressurisation, there would have been warnings on the flight instruments to indicate that the aircraft was not pressurised. While the failure of these instruments cannot be ruled out, the pilot should still have been able to bring the plane down safely by making a tight turn and heading back towards Malaysia – unless something happened like with Helios Airways Flight 522. In Flight 522, the pilots elected to troubleshoot rather than donning their emergency oxygen supplies – which led to hypoxia-induced disorientation before the pilots passed out, leaving the plane to crash after it ran out of fuel.

Assuming that the Inmarsat satellite data and presumed flight route can be trusted, a viable argument might be that Captain Shah was able to control the plane until after the final turn towards the southern Indian Ocean, where he may have then been overcome by hypoxia, and the plane crashed as with Flight 522. However, the flight path seems to suggest that the plane was under controlled flight, which seemingly rules out the possibility of Captain Shah suffering from hypoxia.

The second explanation is a catastrophic fire onboard that brought it down before it could reach safety (Goodfellow, 2014). It is speculated that fire could have started in the cargo hold due to MH370 transporting lithium-ion batteries, a known hazard in light of the fires onboard 787 jets. Such fires could be paralleled to UPS Airlines Flight 6, where an uncontrollable lithium-battery fire in the cargo hold spread rapidly through the aircraft and caused the 747 jet to crash soon after take-off.

This is a straightforward theory, which hypothesised that the pilot turned back, heading straight towards the nearest airport, Langkawi, but could not make the airport in time due to technical difficulties and a lack of time. Communication links may have been severed due to the fire consuming the electrical wirings. However, this theory is problematic for 2 reasons. Firstly, recovered debris showed no signs of a pre-crash fire. Charring, if any, were localised and suggested a post-crash fire (BBC Australia, 2016). Secondly, this theory is self-contradictory: if the fire was catastrophic enough to have caused incapacitation of the pilot, it should logically have burnt through the plane before it could trek across the Thailand-Malaysia border and into the Indian Ocean, as there would not have been anyone actively fighting the fire by that point.

Having almost ruled out the plausibility of this theory, let us examine the third, and most interesting theory – the possibility of a North Korean hijacking and intervention.

Theory 3: North Korea

The North Korean theory advocated for by Redditor Brock_McEwen argues that officials falsified the time that contact with MH370 was lost, and that the plane was actually contacted later by other aircraft in the vicinity. He further speculates that reports, that have since disappeared, indicated a mayday signal from the aircraft, and was coupled with witness reports of a fiery plane crash in the South China Sea alongside a debris field spotted by other passenger jets. The theory claims that satellite images of a debris field were also subsequently removed from the database of the satellite companies that took them (McEwen, 2021).

In this post, McEwen also explains that North Korea most likely ‘cyberjacked’ the aircraft – using internet or communication links to hijack – which led the aircraft to be shot down over the South China Sea. He argues that North Korea did this to show its ability to bring down any aircraft it wants, and that it would do so if provoked or in self-defence. Additionally, he asserts that the ‘official’ consensus, that the aircraft went down in the southern Indian Ocean, is false. Further, he claims that the wreckage found in the Indian Ocean was planted. Mr McEwen explains that a reason for such a massive coverup would be to prevent the collapse of global economies, as air travel is a large revenue generator.

As with the other explanations, this conspiracy theory is easily disproved for a number of reasons. Firstly, North Korea is unlikely to possess the technologies that allow for ‘cyberjacking’. The patent for a similar technology was only filed in 2006 by Boeing, who confirmed that it was not installed on any aircraft (Supra n 1 at section 1.6.10). Nevertheless, even if Boeing was lying, and North Korea has successfully replicated this technology, targeting MH370 seems an odd decision, and one that would have significantly less impact than, for example, downing Air Force One. Besides, if North Korea had wanted to further prove a point through the cyberjacking of aircrafts, we would likely have seen more MH370-style disappearances, given the tensions between North Korea and the West.

Next, the allegations that the wreckage were planted don’t ring true, because it is logistically difficult to mask a salvage operation in the high seas, before transplanting the evidence to a completely separate location. While it might be argued that currents could have brought some of the wreckage to the Indian Ocean, the sheer distance required for the wreckage to travel makes it almost impossible to be the case. Additionally, there is little to no reason for the American, Australian, Malaysian or North Korean governments to collude and conduct such a covert operation, as it would simply pave the way for North Korea to then claim responsibility for the shooting of the plane, using evidence of the wreckage – and the subsequent mass cover-up – as a bargaining chip for what the regime wants.

Finally, the cover-up theory is almost impossible, as it relies on finding a common need for global powers to stay silent against North Korea. Given that more than half of the people onboard MH370 were Chinese citizens, if North Korea had indeed ‘cyberjacked’ the aircraft, such an event would certainly anger China. China is one of North Korea’s closest allies, and would likely turn against the regime, much to North Korea’s detriment. Besides, the logistical arrangement for such a cover-up would likely be prohibitively expensive – far more so than actions such as sanctions against North Korea.

Conclusion

In analysing three of the most popular theories for its disappearance, we are no nearer to the truth behind what happened to MH370. The scant availability of evidence leads to ideas that are often far-fetched and ridiculous, with little to no link between known evidence. This is made worse by alternative news outlets perpetuating alternative theories, where links between the theory and evidence are difficult to draw, in order to increase traffic to their websites.

Thus, I hope that this article inspires you not to buy into compelling theories straightaway, but instead sit down and pick them apart one by one. Regardless of whether we trust official reports and the mainstream media, I believe it is critical that we actively exercise logic and compassion, questioning every fact and evidence brought to the table when determining what truly happened.

Certainly, judgment made regarding this incident must be done with caution and compassion for both the family of those who are missing, and to fellow aviators, who will always find this topic painful to revisit. Speculation without merit only serves to aggravate the grieving families, not just by giving them false hope, but also unnecessarily draining them of their resources and energy in researching and following up on supposed ‘theories’. Only impartial treatment and analysis of evidence from different perspectives can help all of us get closer to the truth and providing the closure needed by the families of the 239 souls on board.

Without doubt, as more evidence might surface in the future, I believe we may be able to join the dots and uncover the truth behind the disappearance of MH370. But until that happens, we should continue to vigorously test theories with every information we have before we claim to know the truth.

References

- Ministry of Transport Malaysia. (2017). Safety Investigation Report, MH370. Ministry of Transport, Malaysia.

- Westcott, R. (16 April, 2015). Flight MH370: Could it have been suicide? Retrieved from BBC News: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-31736835

- Tom Westbrook, J. F. (3 October, 2017). Report on MH370 finds ‘initially similar’ route on pilot’s flight simulator. Retrieved from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-malaysia-airlines-mh370-idUSKCN1C8090

- Australian Transport Safety Bureau. (2017). The Operational Search for MH370. Canberra: Australian Transport Safety Bureau.

- Kitching, C. (17 June, 2019). ‘Depressed’ MH370 captain ‘locked co-pilot out of cockpit and crashed jet’. Retrieved from Daily Mirror: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/depressed-mh370-captain-locked-co-16530787

- Langewiesche, W. (17 June, 2019). What Really Happened to Malaysia’s Missing Airplane. Retrieved from The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/07/mh370-malaysia-airlines/590653/

- Llewelyn, A. (26 February, 2020). MH370 breakthrough: Expert explains plane’s fate as US pilot’s claim ridiculed. Retrieved from Daily Express: https://www.express.co.uk/news/weird/1247339/mh370-news-malaysia-airlines-flight-370-jeff-wise-byron-bailey-spt

- Goodfellow, C. (18 March, 2014). A Startlingly Simple Theory About the Missing Malaysia Airlines Jet. Retrieved from wired magazine: https://www.wired.com/2014/03/mh370-electrical-fire/

- Engel, P. (16 October, 2015). Aviation expert presents a new theory for what happened to missing flight MH370. Retrieved from Business Insider: https://www.businessinsider.com/exploding-batteries-in-mh370-cargo-hold-2015-10

- BBC Australia. (22 September, 2016). MH370 search: Doubts over ‘debris burn marks’. Retrieved from BBC: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-37437651

- McEwen, B. (March, 2021). MH370: New credible evidence of location. Retrieved from reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/MH370/comments/ly736i/mh370_new_credible_evidence_of_location/gqulhw7?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web2x&context=3

- Ohconfucius. (October, 2013). MAS Plane. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MAS_plane.jpg