If you are seeing this video on your TikTok page, then it’s a sign. I am a tarot reader and right now, I am going to do a reading for you. Let’s see what the cards reveal about the month of April for you.

The woman on my phone screen is dressed in what appears to be an excessively bright, billowy kaftan, and almost every part of her body is adorned with some kind of equally bright jewellery. Her voice sounds smooth, almost hypnotic, and I am so entranced by it that for a moment, I miss what she’s actually saying. Sitting in a dimly lit room, she lights a candle, closes her eyes, and mouths something incomprehensible. Then, she picks out two vividly illustrated cards and holds them up to show it to me.

I pause the video. I am not interested in the reading as much as the reach the video has gotten – around three million views, five hundred thousand likes, and twenty-two thousand comments. Most of the comments read “This really speaks to me!” or “I needed to hear this,” posted, I am sure, by scores of millennial and Gen Z TikTokers who were looking for “a sign.”

It was a quiet Saturday morning and like any other Gen Z kid with a phone these days, I had been scrolling through all the different social media apps on my phone when this particular video popped up on my TikTok’s “For You” page. For those who aren’t familiar with the TikTok interface, the “For You” page, popularly abbreviated to “fyp”, is where the app’s algorithm displays videos that are supposedly tailored to your interests.

Now, tarot isn’t really at the top of my list of interests, but I was intrigued by the video anyway. I wanted to find out why young, educated individuals in Singapore were turning to divination as a solution to their worries, instead of more conventional practices like counselling, which was how I came to meet Elaine Mok, a 23-year-old who, among other things, works as the in-house tarot reader at The Moon, an independent bookstore in Singapore.

As she walked into the Starbucks to meet me, I was surprised to see that she looked nothing like the woman I saw just minutes ago on my screen. Nothing about her appearance could make me guess that she was a tarot reader. She sat down and began telling me about how she first got into tarot:

I met tarot with a heavy dose of skepticism because in Singapore it is quite common to believe in empirical sciences as opposed to things like fortune-telling. My first contact with it was purely for aesthetic purposes and I was fascinated by the mystery around it. I started by drawing cards for fun. Gradually, I became more confident with the interpretations and now, here we are!

Elaine was right about one thing – tarot does have a very interesting history. It originated in 15th century Europe as a card game, and it wasn’t until the 18th century that it began to be used as a tool for divination (Decker, Depaulis & Dummett, 1996). Even then, it really only became popular in the last century.

Like any other fortune-telling technique, tarot has seen its fair share of skepticism and scrutiny. The consensus here is clear, and it has been proven time and again: tarot just doesn’t hold up as a legitimate method of predicting the future (Decker, Depaulis & Dummett, 1996). Despite this, interest in tarot as a method of fortune-telling remains popular.

Over the last year, especially during the initial months of the pandemic-induced lockdowns, tarot has seen a renaissance worldwide. In the U.S. alone, online searches for “tarot cards” and “how to read tarot cards” saw a 50% increase in 2020 compared to 2019 (Cartwright, 2020). What originated as a European parlor game meant to keep people entertained has now effectively morphed into a New Age practice shrouded in mystery and intrigue.

Tarot is becoming increasingly popular in Singapore, too. From Today Online to The New York Times Style Magazine, mainstream publications here have featured articles about how young Singaporeans are turning to spiritual practices like tarot as an unconventional form of therapy. Local readers have sizeable followings on Instagram, averaging around 800 to 1000 followers, and receive bookings between five times to seven times a week (Oh, 2019). Most clients, including Elaine’s, are in their late teens to mid-twenties and are mostly female.

Technology has no doubt aided the proliferation of these groups of young people turning to divination. It’s not just meetings and workouts that have pivoted to Zoom; tarot readings have also shifted to the online and video-call realm. In fact, since the pandemic hit, Elaine has been doing readings both in-person and online.

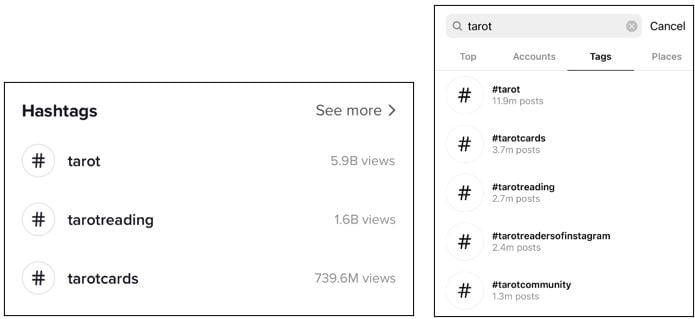

This is why I was hardly surprised when I saw the video of a tarot reading on my TikTok page. From astrology to tasseomancy (tea leaf reading), a number of diviners have set up shop on TikTok and other social media platforms like Instagram (Venkataramakrishnan, 2021), offering their services in compact fifteen or sixty second videos. For tarot alone, related hashtags on TikTok have received views from anywhere between 500 million and 6 billion. So, even if tarot wasn’t something I was extremely interested in, the algorithm works in such a way that trending topics are pushed to the front. In that sense, it’s unsurprising that so many millennials and Gen Zers, who also form the largest group of social media users (Auxier & Anderson, 2021), are exposed to astrology and tarot, and turn to them as an answer to their problems.

On the face of it, the reason why tarot has such a powerful psychological impact and why so many people believe in its predictive power is easy to understand. Tarot uses symbols and archetypes that can be interpreted pretty much any way you want, inviting audience to speculate and come to their own conclusions. The science behind it, however, provides a much clearer reason for why people turn to tarot.

Dr. Gayatri Saikia, a counsellor who focuses on cognitive behavioural therapy, believes the psychology behind making associations and interpretations from tarot readings can be attributed to “The Barnum Effect.” In psychology, this effect is a cognitive bias wherein a person feels that generic information applies accurately to their own unique circumstances (American Psychological Association, n.d.). According to Dr. Saikia:

It is a kind of confirmation bias as well. We humans think that we know ourselves best and when we come across information from astrology or tarot that aligns with our own self-view, it simply acts as a confirmation of our beliefs.

Of course, it’s not just Dr. Saikia who thinks so. Three of the most prominent tarot historians have also expressed the same view – that there is no historical or psychological basis to any of the occultists’ claims about the predictive power or significance of tarot (Decker & Dummett, 2002; Farley, 2009). And yet, more and more young people are turning to it, sometimes to an unreasonable extent.

The risks of tarot

Although there isn’t much research on the dangers of excessive reliance on tarot and other fortune-telling techniques, it is important to realise that fortune-teller consulting can quickly become addictive, especially when started at a young age. A case report published in the Journal of Behavioral Addictions talks about a woman who suffers from “clairvoyance addiction” (Grall-Bronnec, Bulteau, Victorri-Vigneau, Bouju & Sauvaget, 2015). The woman in question first consulted a fortune-teller when she was 19 and then continued to visit fortune-tellers with increasing frequency because she felt it gave her “a reassuring feeling” each time. What began as a harmless endeavor to seek some simple life advice turned into a full-fledged addiction.

In an age where the Internet and social media are increasing the accessibility and availability of fortune-telling practices, there is a risk that more young people will fall prey to such addictions, similar to the increased risks we have seen related to Internet and mobile gambling (Grall-Bronnec, Bulteau, Victorri-Vigneau, Bouju & Sauvaget, 2015). One TikTok or Instagram tarot reading video that seems therapeutic or comforting could lead to another, and before you know it, you could find yourself falling down a slippery slope, questioning every trivial decision in life and looking for reassurance from a tarot reader or astrologer each time you’re worried about something.

This, perhaps, suggests another reason why tarot has proven so enduring. “Admitting that you are facing problems, whether in your relationships or career, and telling someone that you want to start going to therapy has a lot of stigma attached to it,” said Dr. Abhinav Joshi, a holistic psychiatrist at the Ministry of Health in Singapore who also researches extensively on psychospirituality. This could explain why young people look to practices like tarot: it may simply be the easiest solution – after all, whether we are young or old, we are species hard-wired to choose the path of least resistance (Hagura, Haggard & Diedrichsen, 2017).

Looking at the issue in this light, it seems easier to see why some see tarot as an alternative form of therapy. Perhaps offers the “sensual and aesthetic stimulation” that we’ve been missing out on because of the pandemic, as Sabina Magliocco, a professor of sociocultural anthropology at UBC, suggests (Venkataramakrishnan, 2021). An article in the Journal of Parapsychology mentioned that as a reflective practice, tarot reveals “deeply buried conflicts and questions” that may lead to surprising revelations and insights for some (Ivtzan, 2007).

There are precedents for this in history, too. The golden age of spiritualism occurred between World War I and II. During these years, normal people who were horrified by the destruction that the Great War had left behind rejected rationality and placed their faith in spiritualism (Hazelgrove, 1999). So, it is not entirely surprising that during bleak and uncertain times like the one we are experiencing right now, young people are once again seeking solutions and solace in spiritual practices like tarot.

Dr. Joshi mentioned that a part of the appeal of tarot also lies in the fantasy that it provides, the magical side of it. People step into “esoteric communities” like tarot because they are dissatisfied with the answers provided by science and religion (Sosteric, 2014):

When we are frustrated with a lot of aspects of life that religion and science cannot solve and that combines with the ‘agenda’ of a fortune-teller, we are misguided and start seeing these practices as a form of ‘therapy.’ But of course, it is not really therapy.

Somewhat surprisingly, Elaine, the tarot reader, agreed with this view:

Tarot should never be a crutch and you absolutely cannot treat it as gospel. I have turned down readings before when I felt that clients were coming back again and again if they were increasingly anxious about their relationships or any other thing. I also don’t read about physical health because tarot is not the right medium to be asking about that.

At the end of the day, getting a tarot reading done is like holding up a mirror to yourself. The practice is only descriptive and never prescriptive, Elaine told me.

Elaine’s relatively balanced stand on excessive belief in tarot seems to be the exception rather than the rule among tarot readers. Even some prominent scientists have been tolerant, if not supportive, of tarot and other divination practices. Psychoanalyst Carl Jung initially recognized tarot as depicting archetypes and having divinatory characteristics. Jung was of the view that a person could use tarot as an “intuitive method” to understand the present and predict the past (Jung, 1933).

Towards the end of his career, however, Jung himself had doubts about his claims after his experiment to prove the divinatory abilities of tarot failed to manifest. His research was heavily criticized in a 1998 article published in the Journal of Parapsychology where the authors stated:

To do more than ‘preach to the converted,’ this experiment or any other must be done with sufficient rigor that the larger scientific community would be satisfied with all aspects of data taking, analysis of the data, and so forth.

(Mansfield, Rhine-Feather & Hall, 1998)

The late James Randi, also questioned the legitimacy of tarot as a divinatory device:

The fact that the deck is not dealt out in the same pattern fifteen minutes later is rationalized by the occultists by claiming that in that short span of time, a person’s fortune can change too. That would seem to call for rather frequent readings if the system is to be of any use whatsoever.

(Tarot card reading, n.d.)

Evidently, there is no dearth of criticisms on the predictive power of tarot. From a mathematical perspective, the probability of drawing the same deck of cards a second time is extremely slim. Hence, the interpretation that the reader or client made in the first place itself seems arbitrary. In purely scientific terms, it is difficult to see how the reading can be reassuring or therapeutic in any sense. But clearly, that doesn’t mean that it negates the therapeutic effects that tarot has provided to many during the pandemic.

The TikTok video of a tarot reading I watched, in all likelihood, wasn’t a “sign” of anything, yet the appeal of tarot will likely remain for years to come. However, no matter how reassuring the symbols and explanations seem, it is important to recognize the pitfalls associated with an excessive reliance on what was essentially a simple card game developed to entertain the elites in Italian and French courts. As much as we’d all like to have spirit guides on speed dial, the reality simply isn’t that straightforward.